…in the matter of the whole Apsinthion Protocol/liquid girl thing.

Time I guess for another one of my melancholy Dr.-Fausuts-has-no-original-ideas posts.

A word first on how we might have gotten to the strange situation depicted in the panel above, and the provenance of the art. It’s a panel from Weird Science #7, not a comix-format of the 1985 John Hughes movie, but an actual series put out in by famous EC Comics. EC’s publisher William Gaines is an underacknowledged hero of American culture. His comics lines broke new ground in many areas including horror and science fiction. He acted defiant in front of a persecuting congressional committee. He put an African-American character in a position of high competence and responsibility at a time when they were largely confined to menial or comic relief roles in mainstream fiction. And when it became impossible to sustain his comics-making enterprise in the face of cultural backlash, he founded Mad magazine, which I’ll bet did more to train the satirical intelligence of generations of young Americans than any other publication — a latter-day American Mercury for the adolescent set. A great story, which you can find entertainingly told in David Hajdu‘s The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How it Changed America (click on image to the left).

A word first on how we might have gotten to the strange situation depicted in the panel above, and the provenance of the art. It’s a panel from Weird Science #7, not a comix-format of the 1985 John Hughes movie, but an actual series put out in by famous EC Comics. EC’s publisher William Gaines is an underacknowledged hero of American culture. His comics lines broke new ground in many areas including horror and science fiction. He acted defiant in front of a persecuting congressional committee. He put an African-American character in a position of high competence and responsibility at a time when they were largely confined to menial or comic relief roles in mainstream fiction. And when it became impossible to sustain his comics-making enterprise in the face of cultural backlash, he founded Mad magazine, which I’ll bet did more to train the satirical intelligence of generations of young Americans than any other publication — a latter-day American Mercury for the adolescent set. A great story, which you can find entertainingly told in David Hajdu‘s The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How it Changed America (click on image to the left).

But before Mad and all that, EC had Weird Science, a pioneer of science-fiction comics. The stories were largely written by Gaines and Al Feldstein, and drawn by a remarkable set of comics artists the included Harvey Kurtzman, Joe Orlando, and the great Wally Wood. Though the story of this post, “Something Missing!” was written by Feldstein and drawn by Jack Kamen.

Submitted for your consideration: Professor Roger Lawrence is miserably married to Hannah, a shrewish middle-aged woman who rides him hard to give up his experiments and teach more classes so that they can have more money. It’s not his fault: Professor Lawrence’s life is the way it is because he lives in the EC Comics fictional universe, where bitterly unhappy marriages are the norm. They drive plots forward, you see. Lawrence finds comfort in two things: the laboratory in which he has just perfected an amazing machine he calls the “Physio-Chemical Decomposer and Re-aligner,” and his pretty blond undergraduate research assistant, Sally Chadwick.

Lawrence and Sally successfully test the machine on a mouse, which they decompose into slime, then recompose into — a piece of cheese. Sally’s explanation: “…that’s what it was thinking about when the machine dissolved it.” They reverse the process, restoring the mouse. Then, of course, they fall in love.

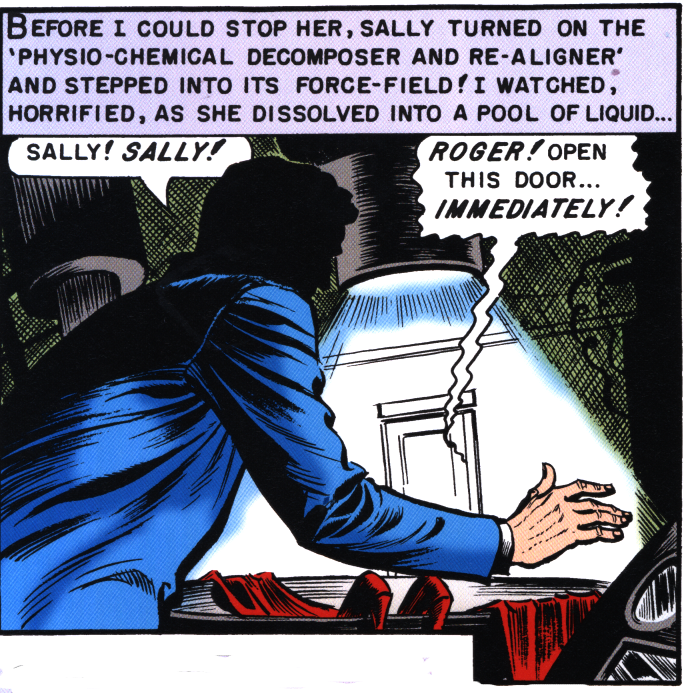

Well, Hannah is not pleased at all when she sniffs out this turn of events. She marches to the laboratory and demands admission. Sally is trapped: there will be scandal, ruin, unless she can improvise a method of escape. And, being a brilliant as well as a beautiful girl, she quickly improvises one — leaping into Lawrence’s amazing machine and melting herself into something else! (Thus the panel above. For the fetishist, the detail of Sally’s abandoned dress and shoes on the edge of the machine really makes the scene.)

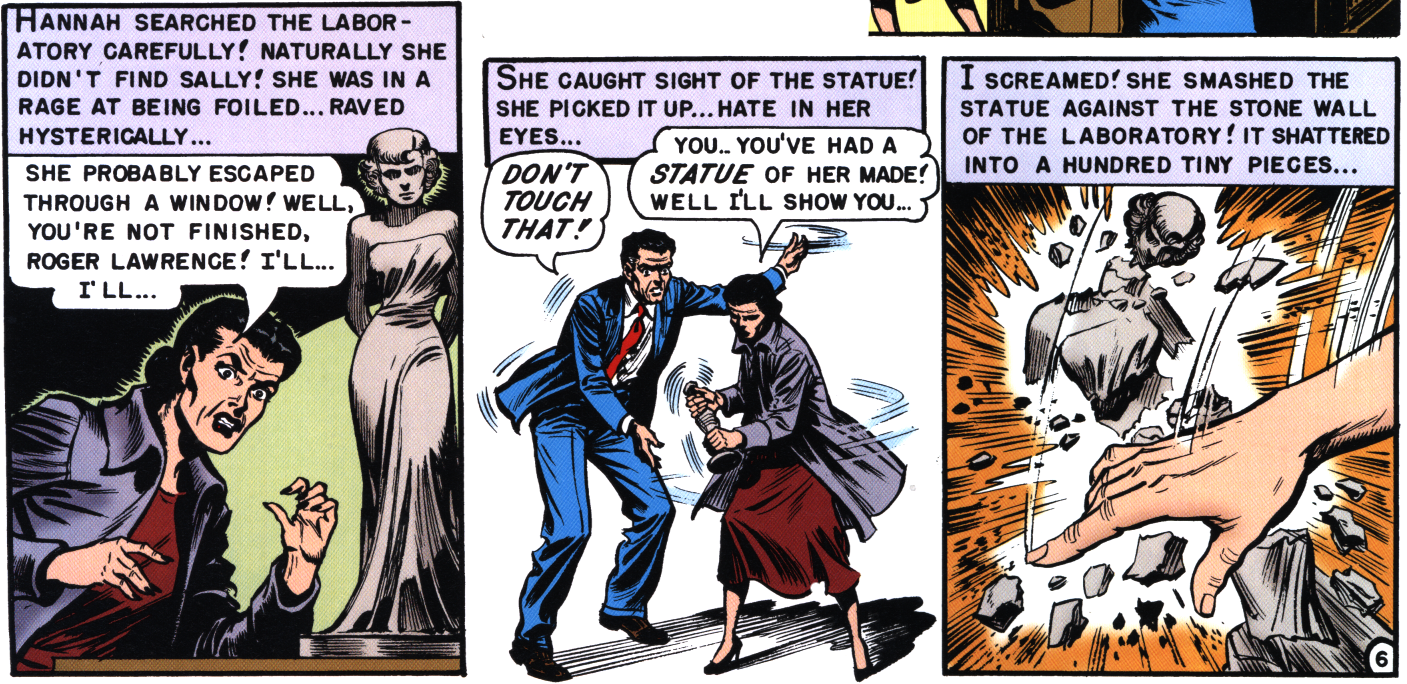

However, this does not work out quite as well as one might have hoped once Hannah storms in.

Doubtless an “oh shit” moment for Professor Lawrence. For Dr. Faustus, though, it was a moment of marvel, because not only has Feldstein anticipated the whole “liquid girl” scenario, but in having Sally turn herself into a statue, he’s also anticipated the whole A.S.F.R. thing. I mean, damn! (And don’t get me started on the whole professor-scientist/student experimentee thing.) Probably the deepest thrill, though, comes from the willingness of the girl to jump into the machine.

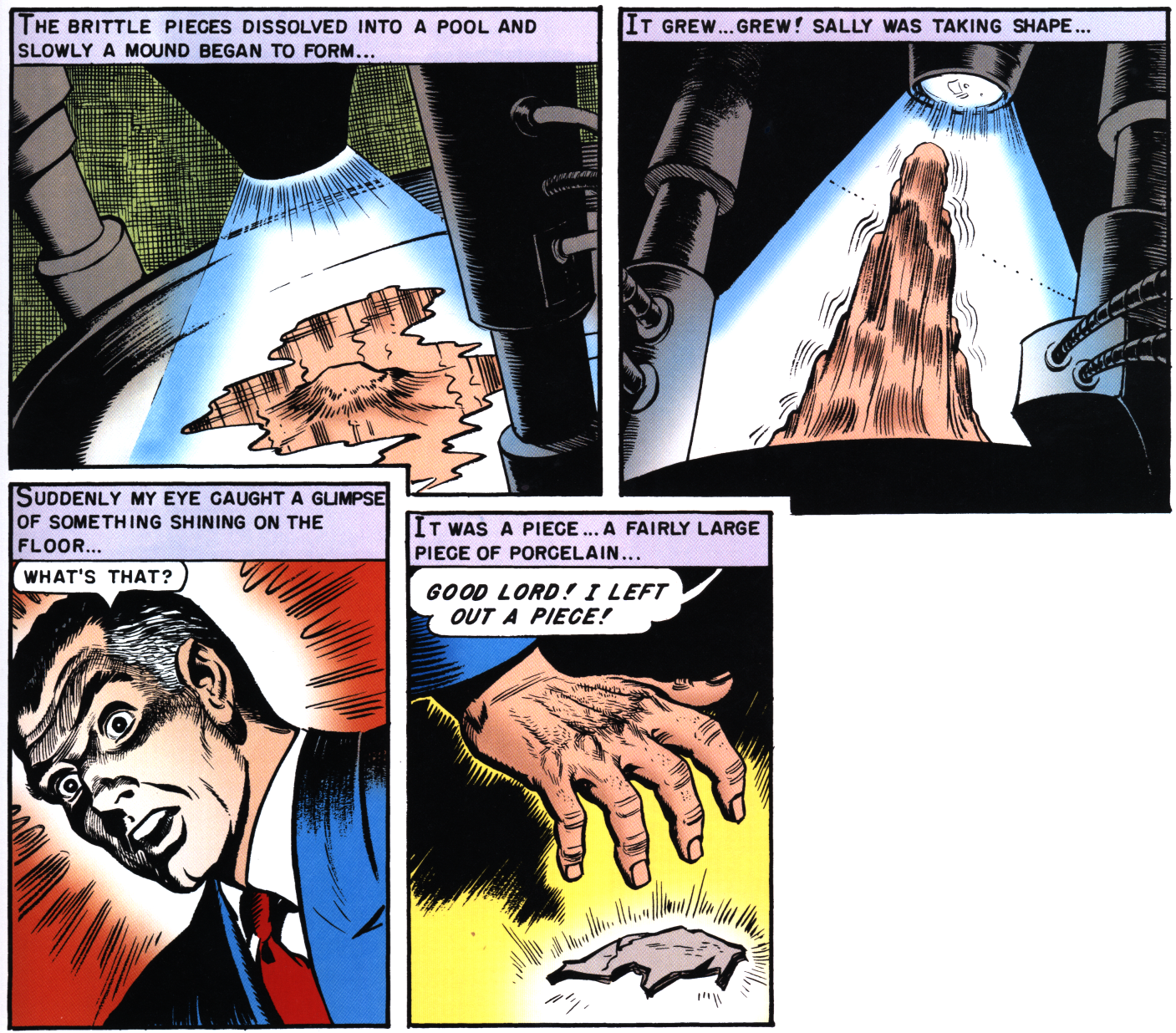

All is not lost, though, because Lawrence still has his machine. Or…

I’ve omitted the last panel, because your imaginations may be better than fiction. But if you really must you can, with some effort, find a reprint of the story.