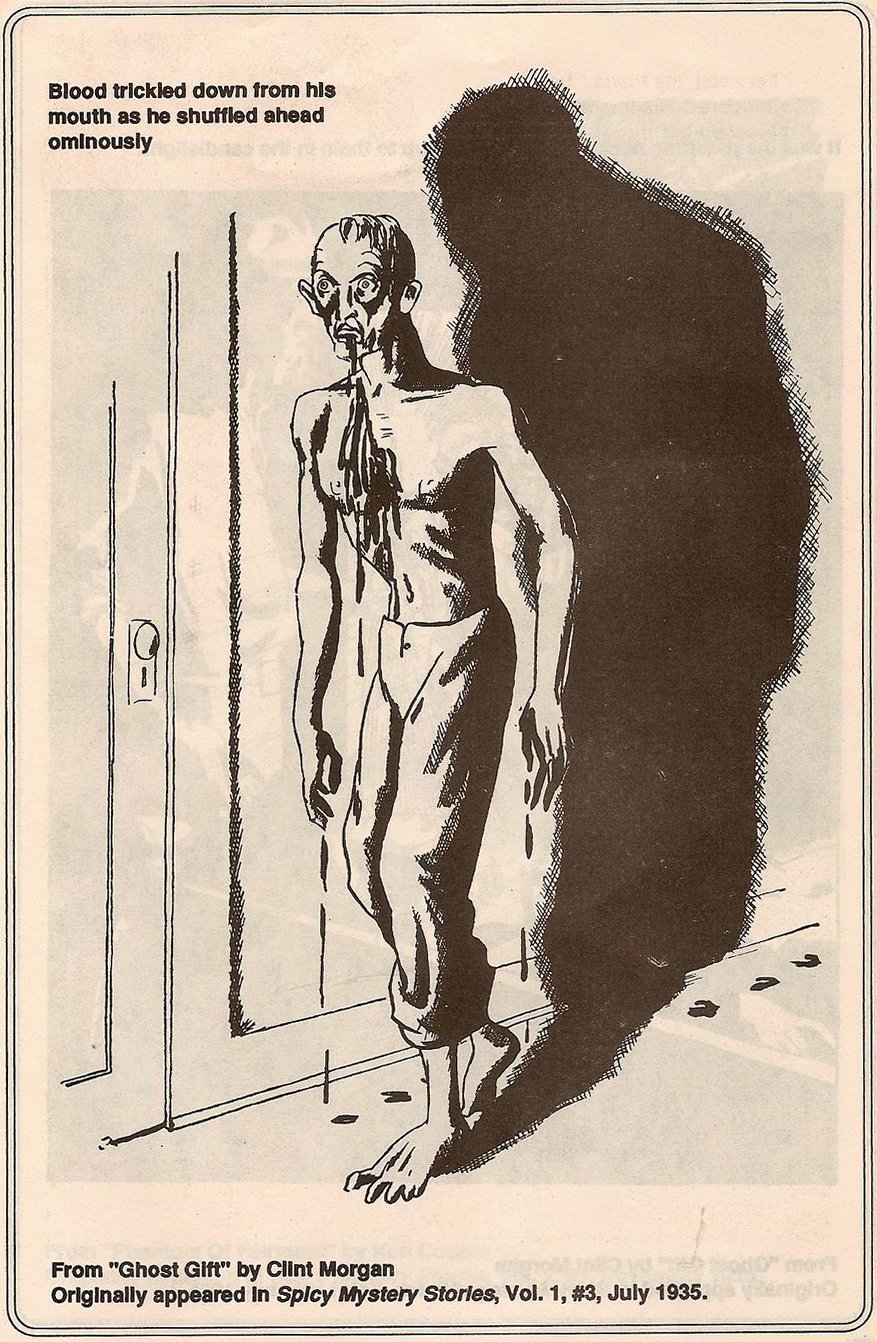

[Note by Faustus: When I first started posting pulp covers here at Erotic Mad Science, I noticed something unusual, which is is that beginning in the 1930s publishers were willing to put forth some remarkably — and to my dirty mind, enjoyably — lurid material on their covers. But this phenomenon of the “shudder pulps” got throttled back dramatically sometime around 1940. Many pulps just went plain out of business, and those that continued to publish did so with considerably tamer art. Puzzled at this phenomenon, I commissioned my friend Bacchus of ErosBlog, a man with a working Internet connection and a bulldog’s instincts wherever anything licentious might be found, to produce a research series on the question of why the shudder pulps faded so quickly. Bacchus’s extensive write-up of his discoveries will be running at mid-day here at Erotic Mad Science for the next few weeks, and I hope you all find it as enjoyable and informative as I did.]

II. Public Backlash Short of Legal Censorship

III. Postal Regulations and Mailing Privileges

IV. NODL-inspired Boycotts and Hybrid Public/Private Censorship

V. Formal Government Censorship, Such As It Was

VI. Replacement of the Pulps by Other Media

VII. Two Additional Hypotheses

Appendix A: Timeline of Shudder Pulp History

Appendix B: Activity of the NODL in 1943

Appendix C: Mayor La Guardia Loses It

Appendix D: Evidence Some Spicies Had Censored Versions

Appendix E: Will Murray’s Informal History of the Spicy Pulps

Appendix F: Canadian Editions of the Pulps

Appendix G: Time Magazine on “Smut Suppression”

I. Introduction

The blazing cometary arc of the shudder pulps is variously explained by different authors. Wikipedia, which along with some other authors prefers to call them “wierd menace” pulps, cites a definitive start date for the genre of 1933, but puts their demise in the “early 1940s”, attributing it to a vaguely-explained “censorship backlash.”

Other accounts have similar dates but offer more varied reasons. Blogger Todd Tjersland’s account of shudder pulp genesis is the standard one:

[T]he “Weird Menace” genre, a bizarre type of erotic horror story that was extremely popular in the 1930s, [was] hitting its peak between 1934-1937 and dying out by 1942. Weird Menace got its start in the pages of Popular Publications’ DIME DETECTIVE MAGAZINE (1933); brisk sales caused the genre to branch out into three “all weird menace, all the time” sister magazines: TERROR TALES (1934), HORROR STORIES (1935) and SINISTER STORIES (1940).

His account of their demise is also fairly standard:

Culture Publications legendary “Spicy” series…were considered so “hot” they had to be sold under the counter, often stripped of their lurid covers. … By the early 1940s, the “Spicy” line had become so notorious that it had trouble finding distribution thanks to censorship; Culture quickly changed the word “Spicy” in the title to “Speed” but it was a short-lived ruse that failed to save the line. Censorship (and the real life horrors of World War II) contributed to the decline and demise of Popular Publications’ weird menace titles around the same time.

If you would criticize Tjersland’s brief account for vagueness, do not; I selected it from among dozens precisely for its brevity. Any deficiencies in detail and citation it may have, it shares with other accounts that are more opinionated and much more lengthy; but for our purposes, it serves admirably. In a nutshell, it introduces the three main factors most often cited for the decline of risque pulps in general and the shudder pulps in particular:

- Censorship

- Distribution difficulties

- Changing popular tastes, due to the war or to the rise of alternative entertainments

However “censorship” and many distribution “distribution” difficulties collapse into a single factor upon consideration; official disapproval and legal sanction, after all, can be a big part of what makes it difficult to put magazines on newsstands where customers can buy them.

In addition, some authors have suggested additional factors, including:

- Wartime resource constraints on paper, labor, or printing supplies

- Easing of depression-era economic pressures that may have brought distribution partners such as newsstand owners into a more risque business than they were comfortable remaining in once business got better

The research has focused primarily on censorship, and the related distribution problems that are, as noted, too closely intertwined with it to be separated. The goal has been to get specific. What where the censorship pressures that the industry faced? Who went to jail? Whose doors had to close in the night? Where information supporting or debunking one of the other factors has come to light, it is noted; but the focus of effort has been on the censorship questions.

II. Public Backlash Short of Legal Censorship

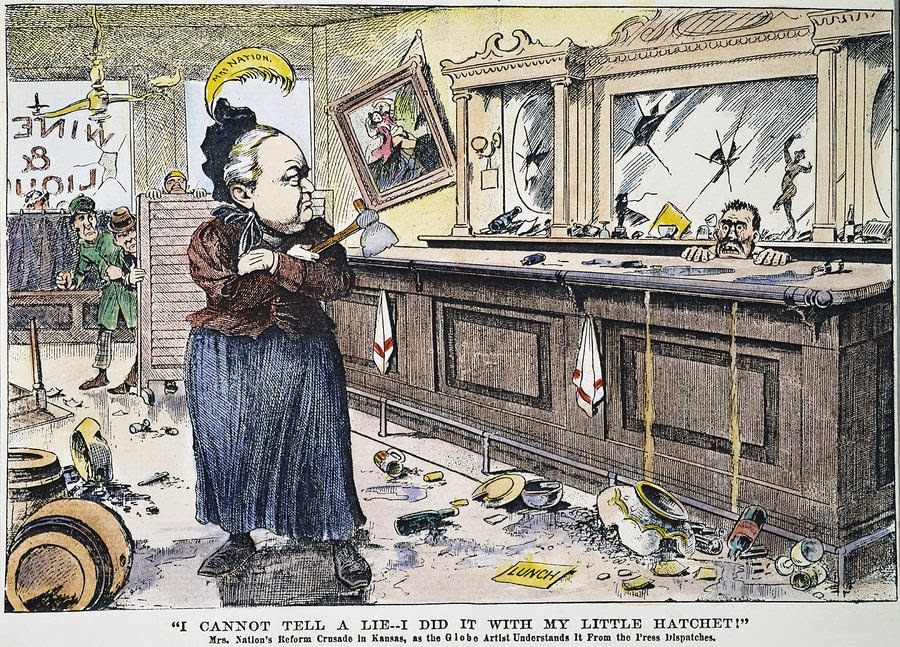

It can be hard, sometimes, to determine whether a particular bit of social pressure is censorship proper (an exercise of government suppression) or “merely” public censure of a particularly robust but more informal kind. It’s the difference between Carrie Nation’s hatchet-wielding saloon-smashers and the formal Act of Prohibition of 1918, if you will; the distinction is strong in theory and rather less important in practice. There was definitely some of both sorts deployed against the most scandalous of the pulps of the late 1930s, and given the extra-legal impulses of machine politicians of the era, clear lines will not always possible to draw.

The most notable — and most often cited — bit of anti-shudder-pulp fulmination and agitation must surely be the nine pages of derisive criticism vomited forth by Bruce Henry in the conservative magazine The American Mercury in April of 1938 under the title “Horror On The Newsstands”. It’s worth reading the whole thing, but the first paragraph alone will set you on the road to understanding the tone:

This month, as every month, some 1,580,000 copies of terror magazines, known to the trade as “the shudder group”, will be sold throughout the nation. Between their frankly lascivious front covers and their advertisements for masculine pep tablets in the rear, these titillating contributions to American belles lettres will contain enough illustrated sex perversion to give Krafft-Ebing the unholy jitters. Never, in fact, since the popularity of the Marquis de Sade, has civilzation seen such a plethora of Frankensteinian literature as is now circulating in this land of peace and good-will. France may have her Grand Guignol, Spain her wartime atrocities, but only in America is it possible for the masses to go in for vicarious Torquemadian exercises through the simple expedient of patronizing the nearest newsstand.

Interestingly, though Henry disapproves of the shudder pulps at great and vituperative length, he nowhere calls for their censorship. It is not inconceivable that The American Mercury’s own 1927 brush with obscenity prosecution explains this restraint; editor H.L. Mencken was tried and acquitted, and an issue of his magazine declared unmailable by the U.S. Postal Service. No, Henry’s article is literary criticism at its most dismissive, but it’s no call for censorship.

Other hints of public disapproval also find their way into the pulp-aficionado accounts of shudder-pulp history. For instance, in Pulp Horrors Of The Dirty Thirties (an essay found in The Pulpster, excerpted here) Don Hutchison writes that in “the early 1940s” “there developed a public rejection of the permissiveness and thrill-seeking of the thirties… As shudder pulp stalwart Bruno Fischer described it “Clean-up organizations started throwing their weight around and gave editors jitters, and artists and writers were instructed to put panties and brassieres on the girls.” Sadly no context for the Bruno Fischer quote is offered.

III. Postal Regulations and Mailing Privileges

It is unclear to what extent the shudder pulps specifically were ever sold by postal subscription or relied upon mail distribution, if at all. The vituperative critic Bruce Henry suggests that they did, and he averred in his infamous 1938 critical expostulation that the horror pulps modified their artwork accordingly to cover “pelvic regions” and breasts without nipples:

“But, say mail inspectors, the illustrations must never show a completely nude wench and the pelvic region must always be obscured in some fashion. Smoke from the bubbling acid vat is usually good camouflage, as is the well-known wisp of silk. Uncovered breasts are admissible, so long as they—quaint fancy — possess no apices, as it were.”

Will Murray, in his Informal History Of The Spicy Pulps, references a specific 1938 threat from the Post Office against Culture Publication’s mailing permit. This is also the most specific reference found to the distribution of these pulps via mail subscription:

In 1938, self-appointed censors began to go after the more conspicuous sex pulps. The heat reached the Culture line, which began to cool the “heat” in its pages. The old tepid descriptions of foreplay were dropped, but the covers remained as racy as before. Culture did this reluctantly, but caved in when the Post Office threatened to remove its second-class mailing privileges, without which subscription copies could not be mailed.

Don Hutchinson goes further, in attributing the 1943 the retooling of the Spicy titles (including their renaming as Speed titles and general toning down after the infamous La Guardia explosion of 1942) in part to “fear of losing…their U. S. postal mailing privileges.” His evidence for this is not indicated. Damon Sasser likewise cites — and likewise doesn’t gesture at any evidence for citing — postal pressure as a major factor in that same big Spicy retrenchment of 1942:

By late 1942, a full court press from all sides was on the Spicy line and Donenfeld and company were forced to take action. In addition to pressure from government officials, changes were needed keep the Post Office Department happy and protect the publisher’s coveted second class mailing rate. So, in an attempt to continue publishing these successful pulps under the harsher censorship and scrutiny, covers were toned down, as was content and interior illustrations and the entire Spicy line was renamed “Speed” to eliminate the word “Spicy.”

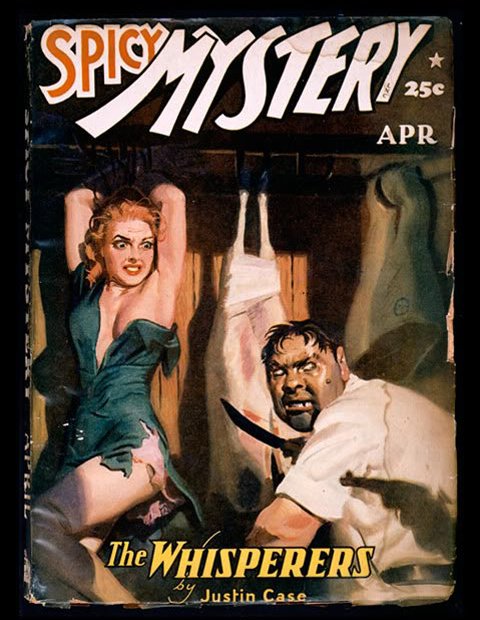

It is well-documented that a Catholic pressure organization called the National Organization For Decent Literatature (NODL), was founded in 1938 to keep “indecent literature” “out of the community”. Its founder, one Bishop Noll, published a cartoon illustrating his intentions in a long-running Catholic publication called “Our Sunday Visitor”. Although that cartoon has proven highly resistant to being turned up in visual form, here’s a written description:

Under the headline “Now is the Time to Act” it showed a bespectacled, boyish-looking middle-aged man — a dead-on likeness of Noll, labelled “Catholic Organizations” — and in a word balloon he said, “We cleaned up the movies, but we’ve let you parasites exist too long.” He was swishing a broom, literally cleaning up a newsstand from which anthropomorphic magazines with tiny legs and feet were scurrying away. They had titles such as Nasty News, Sexy Stuff, Photo Philth, and Cartoon Dirt.

This description is in The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America (2008) by David Hajdu; and although Hajdu does not say precisely when the cartoon was published, he implies it was shortly after NODL was founded in 1938, when shudder pulps might plausibly have been on NODL’s hit list. Per Hajdu, the list was quite literal; it was offically called (at first) “Publications Disapproved For Youth”, though Noll himself called it his “black list.” It was published monthly in NODL’s magazine The Acolyte but not made public for fear that young people “looking for something bad to read” would consult it. (NODL’s “The Acolyte” — no copies of which were found on the internet — should by no means be confused with the roughly-contemporaneous 1940s amateur mimeographed “fantasy and scientifiction” magazine of the same name, some five issues of which may be found in the Internet Archive.)

At some point, NODL began working closely with the Postmaster General (also a Catholic) who by 1943 at least was barring long lists of slightly-risque pulp magazines from the mails, or at least denying their subsidized second-class mailing permits. Moreover, by that time many publishers were “cooperating” with NODL by submitting advance copies of publications for review and making close edits at church direction to avoid trouble with NODL and the post office. A newspaper article provides a lot of detail about the situation in 1943, although it’s too late in time to shed much light on the effect of NODL’s activities on the shudder pulps in particular and it doesn’t directly address the still-uncertain question of how important subsidized mailing privileges were to pulps in general.

Although this research did not turn up any editions of the Acolyte publication or of the NODL blacklist itself, by November 1942 the NODL banned publications list in the Acolyte is said to have grown to 190 “Magazines Disapproved by The National Organization of Decent Literature.” Such a list was still being updated and included in something called the Manual Of the N.O.D.L. (a 222-page publication) as late as 1952. With the 1942 list, NODL noted:

This list is neither complete nor permanent. Additional periodicals will be added as they are found to offend against our code… They are on our list because they offend against one or more of a five point Code adopted by the NODL. [They] glorify crime or the criminal; are predominatly “sexy”; feature illicit love; carry illustrations indecent or suggestive, and advertise wares for the prurient minded.

That the NODL/postal situation was so wretched for pulps in general by 1943 lends credence to the non-specific references in the secondary sources suggesting that the shudder pulps, too, had postal permit issues, especially after 1938 when NODL was founded. However, that same source indicates that postal service revocations of 2nd-class mailing permits did not actually begin until 1942, so the matter is uncertain.

IV. NODL-inspired Local Boycotts and Hybrid Public/Private Censorship

There’s some interesting testimony from a Chicago-based Mrs. Grundy collected in a 1955 Duke Law journal article about comic book censorship. In The Citizens’ Committee and Comic-Book Control: A Study of Extragovernmental Restraint (John E. Twomey, 20 Law and Contemporary Problems 621-629 (Fall 1955)), Twomey specifically references a NODL-inspired church-lady boycott effort that was impaired, in part, because of the sheepishness of the volunteers who had to purchase and review weird horror and sexy titles to determine their suitability for Catholic youth. The article looks in detail at the Citizens’ Committee for Better Juvenile Literature of Chicago, Illinois, founded in 1954 to suppress comic books. But of interest here is that the committee’s primary organizer was one Mrs. Robert V. Johlic, who “had been a representative to the former Committee from the Council of Catholic Women of the Archdiocese of Chicago, with which organization she had, for six years, participated in and directed parish-wide decency crusades in cooperation with the National Organization for Decent Literature.” Johlic, a footnote reveals, is at this time actually the person who oversees the compilation of the national NODL “black list”, and NODL’s methods become the Committee’s methods as well, not limited to comic books alone:

The greater part of the Committee’s activity, however, falls under its third objective-i.e., the elimination of “detrimental literature,” which has been interpreted to include pocket-size books, popular magazines, and “girlie” magazines as well as crime and horror comic-books. The technique adopted has been that of the National Organization for Decent Literature: a wide variety of popular publications is regularly purchased; these are read by volunteers who judge them in accordance with established criteria; a list of publications judged “objectionable” is regularly promulgated; and this list is then distributed to organized teams of surveyors who visit neighborhood retail outlets and request that listed items be removed from display and not be sold. Due to the inexperience and limited number of its members, the Committee has often been forced to use NODL lists, but a volunteer reading program has been inaugurated.

This is all happening twenty years after the era of the shudder pulps, but you wouldn’t know it from the sample title Johlic makes up when talking about the challenges of her volunteer reader program:

We’ve also had a problem with some of our readers (women who volunteer to appraise the current material) who are too shy. I mean, you feel kind of silly riding home on the IC studying a copy of Nude Models or Weird Horror Tales. We’re getting around that problem by providing each of the readers with a large brown envelope to hide the magazines they’re studying.

In truth, Google doesn’t verify that any publication had used the precise title “Weird Horror Tales” prior to Johlic’s testimony in 1954, although several have since; but it’s certainly reminiscent of many shudder pulp and/or horror comic titles she would have seen and disapproved of.

The real payload of the article, though, is that it catalogs, footnoted to Johlic’s testimony, a depressing laundry list of self-appointed civic organizations who cooperated in suppressing disapproved titles, and reveals that local police stood ready to act (apparently informally in ways that don’t leave much of a trail for researchers) against any vendors who resisted this civic pressure:

There have also been instances when retailers unequivocally declined to cooperate with surveying teams. Only once, however, in its first year of operation, has the Committee found it necessary to call upon the Chicago Police Censor Bureau to exert pressure to enforce compliance as this willingness of the Police Censor Bureau to support the Committee’s activities, incidentally, is perhaps one of the Committee’s most potent instruments of persuasion.

In addition to its surveying activities, the Committee maintains close liaison with other organizations engaged in combatting “objectionable” literature, some of which look to the Committee for leadership, and others of which carry on separate campaigns. Among these organizations are tle Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Chicago Retail Druggist Association, the Camp Fire Girls, the Illinois Federation of Temple Sisterhoods, the Illinois Youth Commission, the Grandmothers’ Club of Chicago, the Association of University Women, the Chicago Region PTA’s, the Woman’s Auxiliary of the Episcopal Diocese of Chicago, the Illinois Council on Motion Pictures, Radio, Television, and Publications, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, and the National Organization for Decent Literature.

It is unclear what the Chicago Police Censor Bureau may have been or how it would “enforce compliance” with the demands of Mrs. Johlic and her blue-nosed Committee church ladies. But I think it’s fairly safe to assume that we are looking here at a snapshot of the fully-evolved tactics that the pulp industry would have been dealing with in nascent form in the late 1930s: a complex web of self-appointed civic and religious pressure groups backed when necessary by local police and government authorities acting as informally as possible because, even then, true censorship required post-hoc successful and difficult-to-obtain obscenity prosecutions and prior restraint of the sort desired by the Grundys was mostly unavailable to the law. All of this, organized separately in each of the major cities of the America: a nightmare distribution problem for any national publication, because it’s impossible (even with Johlic writing national lists for NODL) to ever get all these local bluenoses on the same page. And all of them, one way or another, able to get strong-arm support from local officials in police or municipal government.

V. Formal Government Censorship, Such As It Was

There can be little doubt that from the earliest days of the shudder pulp / weird menace publishing boom, the publishers of these magazines were raking in their dough with one eye firmly on the door of the counting rooms, watching for the censorious police to break it down and end the party. This paragraph in Will Murray’s “Informal History of The Spicy Pulps” is particularly telling:

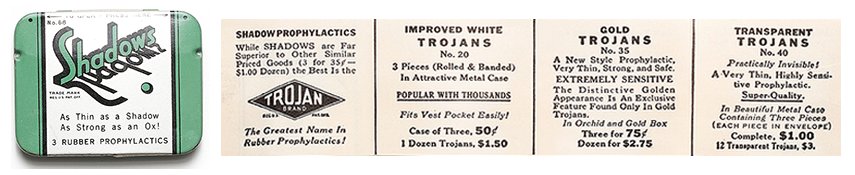

But the Spicies were not all Culture-published. They inaugurated a related line under the Trojan Publishing Company name. The inspiration for the firm’s name is open to speculation. Its first title was Super Love Stories in 1934. The Trojan arm of Culture Publications was its more legitimate expression. Trojan eschewed salaciousness and published mainstream pulps. They were sold from the same racks that featured other pulps. Whether or not the Spicies were sold on newsstands or under-the-counter depends on who you talk to — but actually this may have varied according to where they were sold. It’s likely Trojan was incorporated as a separate entity to protect that line in case obscenity suits or censorship problems wiped out the Culture titles.

Note the dates! Trojan Publishing Company’s supposed prophylactic business purpose (and yes, that double-entendre was available to the men who owned Trojan Publishing Company) is consistent with its establishment in the same year as Modern/Culture Publications, and Trojan was operated conservatively throughout the Spicy’s spectacular run, and beyond. When the Spicy titles got renamed “Speed”, the listed publisher was Trojan, and the new titles were reduced in salaciousness to match the more-conservative Trojan house positioning.

Here’s Murray again:

Official pressure had continued against the Spicies. New York’s mayor Fiorello La Guardia prevented the titles from being sold in Manhattan unless the covers were removed. Culture realized that they’d run their course. They’d established hot titles in the big four pulp genres (only a Spicy Science Fiction Stories was overlooked — but then Spicy Adventure and Spicy Mystery did a lot of SF stories and covers in the early forties), diversified enough to cover their losses in any situation, and sales had slacked off. Frequently, older stories would be reprinted under new house bylines. So they finally killed off the Spicies. But that wasn’t the end, by any means. At the beginning of 1943, Trojan started four new titles. Speed Adventure, Speed Detective, Speed Mystery and Speed Western Stories. Most were cover-dated January 1943. They weren’t as racy as the Spicies, but in their own way they were “fast.”

What’s fascinating here — if perhaps not directly germane to shudder pulp history — is that that the Amer/Donenfeld partnership at Culture/Trojan got its start in the early 1930s with a similar censorship-ducking dodge, as Amer defused an earlier wave of censorship aimed at his long-running girlie pulps of the 1920s:

In May 1932, Armer surrendered the gems of his line, Pep Stories and Spicy Stories, to Harry Donenfeld for printing debts owed; in like manner, Donenfeld accrued many girlie pulp titles during the 1930s… Bowing out gracefully, Armer did Donenfeld an additional service by making a ploy to deflect the censors part of the deal.

In spring 1932, the New York Committee on Civic Decency had pressured the police to arrest four newsstand owners for selling girlie pulps. At a July meeting with the Committee, charges against the four owners were dropped after Armer and other editors promised to “tone-down” their content and “pay closer heed to the proprieties” — as well as cease publication of Ginger Stories, Hollywood Nights, Gay Broadway, Broadway Nights, French Follies, and La Paree. Donenfeld continued to print La Paree in spite of this agreement, and in addition to Ginger and Broadway Nights, Armer probably had a controlling interest in Henry Marcus’ (Pictorial) French Follies and Hollywood Nights. So Armer’s pulps, which were going out of business in any case, became the sacrificial lambs, while newsstand owners were off the hook — at least for the time being.

We have established that the men who were gearing up to publish salacious pulps — including shudder pulps — in the 1930s were alert to the risks of formal censorship, and experienced in handling those risks. But what censorship activity did they actually face, and what were its effects on the shudder pulp business?

One name that comes up over and over again is that of New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. A notorious prude and blue-nose remembered at least as vividly for putting burlesque theaters out of business, La Guardia seems to have ruled mostly by bare-knuckled administrative fiat, leaving not much paper trail behind his billy-club-toting cops. Most of what survives about his pulp censorship efforts is colorful summary and commentary. I’ve compiled that in a couple of stand-alone articles, which can be boiled down here as follows:

- In 1934, as reported in Time magazine, La Guardia issued some sort of order to the police directing that 59 salacious magazines be no longer exhibited or sold at New York City newsstands. Titles included Spicy Stories, publishers listed included Culture Publications, and Harry Donenfeld gives a juicily obnoxious quote. There is promise of litigation from multiple parties, including the “Civil Liberties Union.”

- Numerous sources refer to “a new decency standard after 1938” or “censorship in 1938” with Mayor La Guardia fingered as the cause. Perhaps it is also no coincidence that NODL was founded about this time.

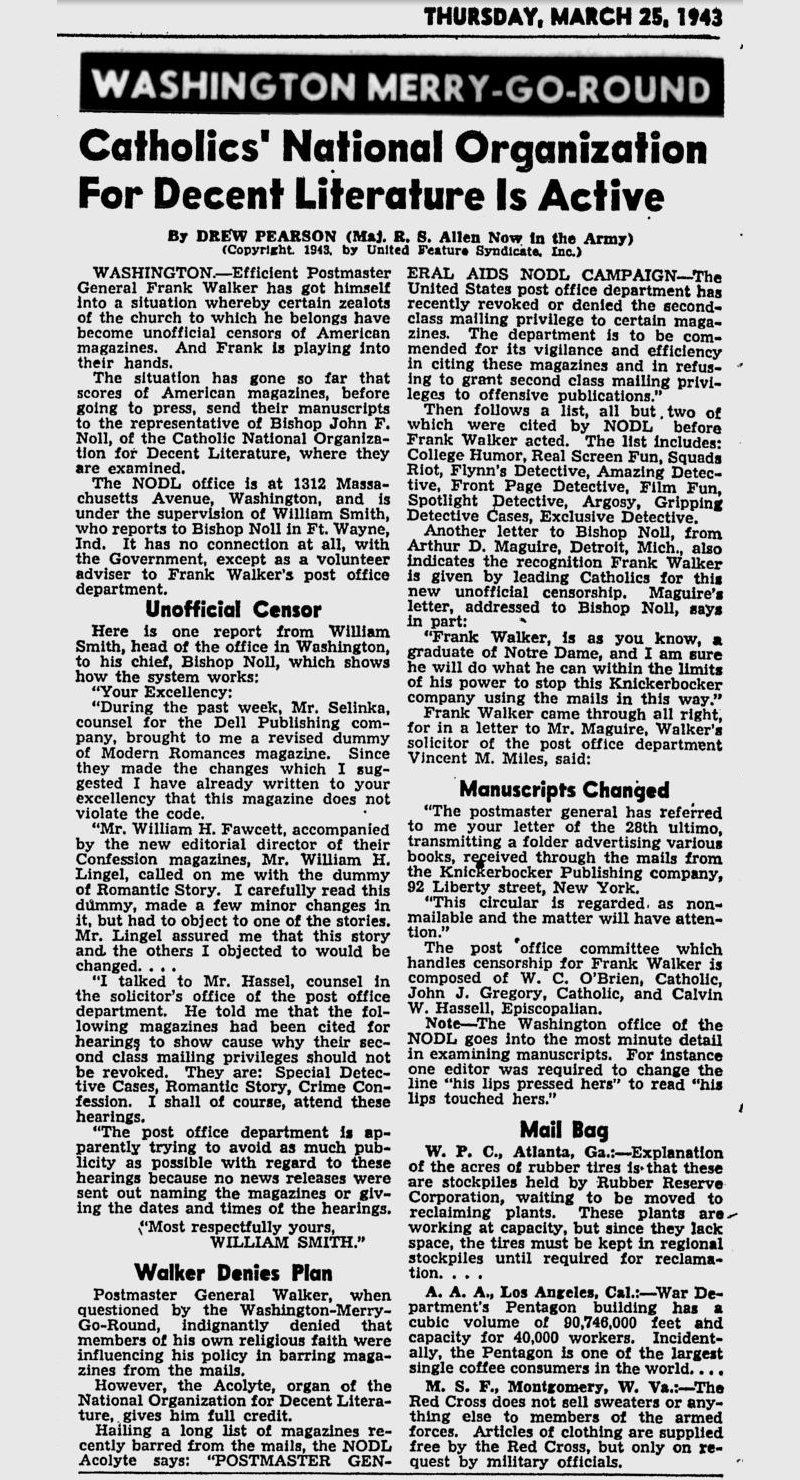

- Finally, there is Mayor La Guardia’s infamous staged explosion for reporters in 1942, when he lost his mayoral shit upon seeing a copy of the April 1942 Spicy Mystery Stories. T However, whatever effect Mayor La Guardia’s stunt did or did not have on the publishing environment for Spicies in New York City in 1942 and subsequently, most shudder pulps had already ceased publication before that fateful (or not) day.

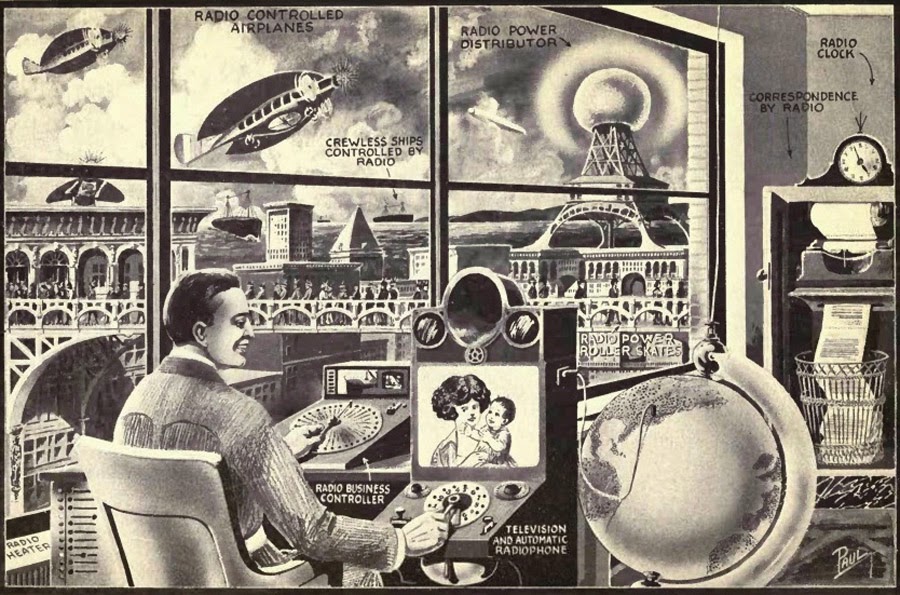

VI. Replacement of the Pulps by Other Media

There’s a discussion here (informed by, and perhaps quoting, although the extent of quotation is unclear, Ron Goulart’s Dime Detectives book) arguing that pulps were completely supplanted by paperback books and television (the discussion apparently omits/forgets comic books). Although television is largely a post-WWII phenomenon, the paperback book boom began in 1939, which is, timing-wise, appropriate to be a nail in the shudder pulp phenomenon. It’s appropriate here to point out that, as Will Murray pointed out in his Informal History Of The Spicy Pulps, the shudder pulps could not even begin to compete with the paperback book industry for salaciousness:

“The new and burgeoning paperback industry pushed the limits of propriety leagues beyond anything Armer envisioned; they dealt directly with themes like interracial love, homosexuality and other once-taboos, leaving the entire Culture/Trojan approach to sex stories in the dust and rendering the very term “spicy” antique.”

Blake Bell, writing in his 2013 book The Secret History of Marvel Comics: Jack Kirby and the Moonlighting Artists at Martin Goodman’s Empire about the one-issue run of Martin Goodman’s 1941 Uncanny Stories, said the short run

“was symptomatic of what was happening in the pulp industry. Pulps were dying, even banned in Canada, comic books were on the rise, and World War II was about to put a crunch on paper supplies.”

(Note: the reference to a pulp ban in Canada apparently refers not to any sort of censorship relevant to this research, but to >a purely protectionist trade ban on imports of US pulps, a subject which will merit a future post of its own.)

As pulps declined in general, the way magazines were published and distributed was changing too. Jane Frank, writing on the website of LonCon 3, the 72nd World Science Fiction Convention, says that pulp sales generally were in decline by 1938 and that distribution was lacking: “In 1938 the magazine industry was in the process of transforming itself, from one based on many independently published pulp magazines to one based on magazine chain ownership. The pressures of decreasing sales and lack of distribution caused many pulp publishers to sell to larger magazine chains.”

Years later, more distribution changes appear to have put the final nails in the coffin of the pulp industry generally. Writing about the economic impact of the Comics Code in 1954, Lawrence Watt-Evans says:

The comics market was declining at the time anyway, and at very nearly the same time that the Code came in there was a major shake-up in the magazine distribution system — the American News Company, by far the largest distributor in North America, was liquidated by its stockholders. The result was that the other distributors didn’t have the capacity to handle all the magazines being published, and were able to pick and choose which they would handle.

Naturally, they picked the more profitable ones.

That was what finally killed off the pulps; they’d been fading for years, and the distribution realignment finished them off. Fiction House folded completely; several other pulp publishers managed to get into publishing “slicks,” as the glossy, higher-priced magazines were called.

VII. Two Additional Hypotheses

Decline Of Interest In Horror/Weird

In his Pulp Horrors Of The Dirty Thirties essay previously cited, Don Hutchison took the view that World War II and its horrors affected the national mood in a way that began to drive nails into the shudder-pulp coffin:

“With the coming of World War II, the extent of human madness and misery could no longer be viewed — much less enjoyed — as mere fiction. In a more innocent time, it was thought that the brand of horror perpetrated by the fiends of the shudder pulps was purely imaginary. Now people knew that such things — and worse — were possible.”

Of course there are timing issues to be considered; the worst horrors of WWII came to light long after shudder pulps were history. Still, blogger Terrence Hanley is in accord, explaining the demise of a particular title:

[The shudder pulp titles] Terror Tales and Horror Stories came to an end a year later, in spring 1941. By then, torture, blood, and violence were no longer mere abstractions, for World War II had begun. Fiends and madmen ruled not just the pages of pulp magazines but also half the planet.”

War-Related Resource Constraints

War-related resource constraints are often cited without much evidence in broad-ranging opinion pieces about the demise of pulps more generally. It is true that paper rationing, labor shortages, and possibly constraints on availability of printing equipment and supplies all constrained various parts of the print entertainment industries in the early 1940s. But as the timeline makes clear, the shudder pulps in particular were closing doors left and right by 1941. Thus, this research did not seriously consider war-related resource constraints on the shudder pulp trade. See, e.g., Blake Bell’s observation (above) that “pulps were dying” in early 1941 at a time when WWII was “about” to put a crunch on paper supplies and thus had not yet done so. The Secret History of Marvel Comics: Jack Kirby and the Moonlighting Artists at Martin Goodman’s Empire (Blake Bell, 2013)

VIII. Conclusion

There seems to be little evidence that either the shudder pulps specifically, or the broader constellation of risque pulp magazines in which they were bright-if-ruddy stars, were ever much in the sights of serious, direct, formal government censorship pressure. If a shudder pulp title ever lost a postal mailing permit, or a shudder pulp publisher or editor ever got charged with or tried for or convicted of obscenity in any US jurisdiction, this research turned up no evidence of it. Even such occasional bans as may have happened appear to have been local and/or informal and/or temporary.

However, it does appear that as the shudder pulps exploded in 1938, a sort of popular backlash was also getting underway, exemplified but by no means limited to the rise of NODL and by New York Mayor La Guardia’s increasingly strident expression of his long-standing antipathy to smutty pulps of all kinds. There’s every indication that the entire risque portion of the pulp industry, published overwhelmingly by veterans both tired and wiley, were careful to stay ten steps ahead of that backlash at all times, making all necessary changes in plenty of time to prevent precisely the sort of formal censorship that we could look back on from 2017 and say with certainty “There! That’s when they were censored.” And yet, in the big picture, it seems clear that between 1938 and 1942 there was a marked decline in the freedom of the shudder pulps to publish their signature “weird menace” content and in the inclination of their publishers to risk it. Whether the disappearance of shudder pulp from the market by the time the US entered World War II is because the market lost its taste for the content or the publishers never had a taste for the amount of hassle and risk that began to build after 1938 remains an open question. And if the rise of comic books and paperbacks had not already mooted the question, they soon would.

Appendix A: Timeline of Shudder Pulp History

A few of the most key events in the history of the shudder pulps, arranged chronologically:

- 1933 — Dime Detective Magazine begins (Popular Publications) begins publication

- 1934 — Terror Tales (Popular Publications) begins publication

- 1934 — Horror Stories (Popular Publications) begins publication

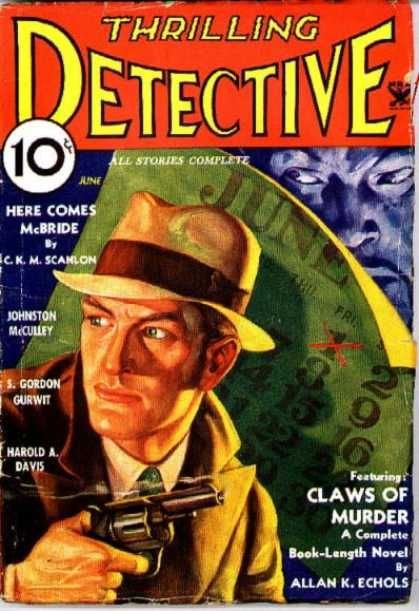

- 1934 — Spicy Detective Stories (Modern Publications, later Culture Publications) begins publication

- 1934 — Spicy Adventure Stories (Modern Publications, later Culture Publications) begins publication

- 1934 — Spicy Mystery Stories (Modern Publications, later Culture Publications) begins publication

- 1934 — Snappy Adventure Stories (Modern Publications, later Culture Publications) begins publication

- 1934 — Snappy Detective Stories (Modern Publications, later Culture Publications) begins publication

- 1934 — Snappy Mystery Stories (Modern Publications, later Culture Publications) begins publication

- 1934 — March — 59 magazines temporarily banned from sale in NYC newsstands by Mayor La Guardia, according to Time. National circulation of 11 popular titles: 30,000.

- 1935 — Horror Stories (Popular Publications) begins publication

- 1937 — Detective Short Stories (Goodman, later Marvel) begins publication

- 1938 — Complete Detective (Goodman, later Marvel) begins publication

- 1938 — Mystery Tales (Goodman, later Marvel) begins publication

- 1938 — April — 1.58 million horror pulps sold in America, according to critic Bruce Henry, losing his shit in conservative magazine The American Mercury

- 1938 — Mayor La Guardia seems to have indulged one of his periodic impulses toward censorship, although details are unavailable; see “The Blue-Nosed Mayor”

- 1938 — Catholic pressure group National Organization For Decent Literature founded

- 1940 — Startling Mystery (Popular Publications) begins and ends publication

- 1940 — Sinister Stories (Popular Publications) begins and ends publication

- 1940 — May — Mystery Tales ends publication.

- 1941 — April — Uncanny Stories (Goodman, later Marvel) begins and ends publication)

- 1941 — “Actions of blue-nosed watchdogs help propel weird menace magazines from market” per Don Hutchison essay; details not specified.

- 1941 — March — Terror Tales (Popular Publications) ends publication

- 1941 — April — Horror Stories (Popular Publications) ends publication

- 1942 — April — The infamous “Mayor La Guardia Sees Spicy Mystery” anecdote, resulting, depending on whose account you credit, in the final end of Spicy Mystery, or merely its sale in NYC under counters or without covers

- 1942 — Spicy Adventure, Spicy Detective, Spicy Mystery and Spicy Western Stories (all from Culture Publications) cease publication, to reappear in early 1943 as the toned-down Speed Adventure, Speed Detective, Speed Mystery and Speed Western Stories from Trojan Publishing Company

Appendix B: Activity of the NODL in 1943

This story from the United Feature Syndicate appeared in the St. Petersburg Times in 1943. It documents “unofficial censors of American magazines” in the form of the Catholic organization the National Organization For Decent Literature. Founded in 1938 (the height of the shudder pulp era), NODL was said to be working closely with the postmaster general (himself a Catholic) by examining “scores of American magazines” on his behalf, advising magazine editors on close edits they must make to satisfy “the code” and communicating with lawyers at the post office about magazines that should or should not have mailing privileges revoked. NODL’s own publication, called the “Acolyte”, cited with approval “a long list of magazines barred from the mails” — which is to say more precisely, denied the subsidized second-class mailing rate. These are pulps, but the era of the shudder pulp is already past, so titles are pulpy but more tame: “College Humor, Real Screen Fun, Squads Riot, Flynn’s Detective, Amazing Detective, Front Page Detective, Film Fun, Spotlight Detective, Argosy, Gripping Detective Cases, and Exclusive Detective.” Again, these are the titles excerpted for the article from a much longer list. To whatever extent that mail distribution was important to what remained of the pulp magazine business by 1943, the NODL campaign combined with postal revocation of mailing privileges seems to have been cutting a large swathe out of that business. The article therefore tends to lend credence to reports that various shudder pulps came under pressure to tone themselves down in the late 1930s to preserve their mailing privileges.

Appendix C: Mayor LaGuardia Loses It

There are so many accounts of New York City mayor La Guardia’s infamous explosion upon seeing a particular Spicy Mystery cover in 1942 — and so much impact on the shudder pulp industry attributed, probably falsely, to the incident — that it seems sensible to accumulate all of the anecdotes in one place for comparison and contrast of details. It’s worth pointing out that the the shudder pulps in general were well into their terminal decline at this point (see timeline) and that any fallout or follow-through from this incident would not have been La Guardia’s first attempt at censoring pulp magazines in NYC; those began at least as early as 1934 (see the “Smut Suppression” article from Time.)

From The Village Voice in 2003:

In 1942, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia spied a Spicy Mystery magazine on a New York City newsstand. H.G. Ward [sic; reference should be to H. J. Ward] (a pulp cover artist who never missed the chance to lovingly delineate a mons veneris under clingy fabrics) had portrayed a woman strung up in a meat locker and threatened by a hunchbacked butcher. Apparently missing the compositional nod to Caravaggio’s Abraham and Isaac, Hizzoner forced the publisher out of the pulp business.

(Spicy Mystery underwent a name change and a shuffle in corporate ownership, but in truth La Guardia’s famous fit of pique did not, at least by itself, force anybody out of business.)

Blogger Terrance Towles Canote wrote in a 2014 piece on the decline of shudder pulps:

The cover of the April 1942 issue of Spicy Mystery came to the attention of New York City mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia. The cover featured a woman, her clothes in tatters, dangling from a meat hook in a freezer, while being menaced by a hoodlum with a large and sharp looking knife. Mayor La Guardia,who had cracked down on the spicy pulps and other “dirty magazines” in the Thirties, then cracked down on pulp magazines. Even more mainstream pulp magazines such as Weird Tales, would be affected by the mayor’s crackdown on the pulps; its covers by Margaret Brundage would be considerably tamer afterwards. As to the shudder pulps and the much racier spicy pulps, they more or less ceased to be.

Almost everything that follows the anecdote here is wrong, or at least hopelessly confused as to timeline. According to Wikipedia and other sources, Margaret Brundage stopped drawing sexy covers for Weird Tales in 1938, possibly in part because of La Guardia’s earlier pressure on pulp publishers. And the shudder pulps were pretty much finished already by 1942 when La Guardia blew his top. Finally, there’s very little documentation (as the rest of these collected anecdotes will show) of what, if anything, La Guardia did in a concrete way to burden pulp distribution in NYC after exploding in an indignant show for the reporters.

The Smithsonian Magazine goes so far as to put actual words in La Guardia’s mouth:

When New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia passed a newsstand in April 1942 and spotted a Spicy Mystery cover that featured a woman in a torn dress tied up in a meat locker and menaced by a butcher, he was incensed. La Guardia, who was a fan of comic strips, declared: “No more damn Spicy pulps in this city.” Thereafter, Spicies could be sold in New York only with their covers torn off. Even then, they were kept behind the counter.

Some version of the claims in those two final sentences is often repeated, but documenting them from original sources has proved elusive. Although the Spicies did not long exist after that (see main article and timeline) cause and effect are harder to put in proper order.

This next account tends to support La Guardia’s quoted words in the Smithsonian story, fairly closely anyway:

One day in April 1942 Mayor la Guardia spied an unusual Spicy mystery on the newsstand and exploded in instant rage. He ruled on the spot: “No more Spicy pulps in this city.”

That’s said to be from the book Pulp Art by Robert Lesser (Gramercy Books 1997).

Another account of La Guardia’s reaction comes from Damon C. Sasser, who tells it thusly:

When New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia spotted the April 1942 issue of Spicy Mystery Stories magazine on a newsstand that sported a cover depicting a woman strung up in a meat locker being menaced by a homicidal butcher, he declared war on the Spicy line. The Mayor decreed that any magazine with a lurid cover had to be sold with the cover removed. Sadly, Margaret Brundage’s Weird Tales covers were among those singled out for destruction.

Again, no contemporary documentation of any such “decree” has been located.

The New York Times tells the same story, with a lot more color but omitting any mention of action on La Guardia’s part except for the angry noise all seem to agree that he made on the spot for reporters:

Mayor La Guardia was appalled. Out for a walk one day in Manhattan in 1942, he happened upon a store displaying a copy of a periodical called Spicy Mystery. In lurid hues and slashing graphic style, its cover pictured a curvaceous, terrified young woman in a partly shredded dress hanging by bound hands from a hook alongside slabs of meat. She was menaced by a demented, knife-wielding brute of a man who looked back over his shoulder at whoever was holding the gun that cast its shadow on him. Shocked and dismayed, the mayor vowed to ban all such scurrilous literature from his fair city.

All agree: this was a colorful moment of mayoral choler. The impact, if any, it had on the ongoing decline of the shudder pulps is rather more debatable, but the murky truth is a lot harder to nail down than this colorful anecdote is to tell.

Appendix D: Evidence Some Spicies Had Censored Versions

The following faint archival spoor survives to suggests that some of the Spicy titles existed in multiple versions as a presumed response to censorship pressure. This is one of those facts from which censorship can be inferred, just as the presence of an immune response to a specific virus is evidence of exposure to the virus. Here’s the email as found, followed by its heavily-degraded provenance:

From: “Phil Stephensen-Payne”

Date: 17 June 2006 13:08:39 GMT+04:00

To: fictionmags@yahoogroups.com

Subject: [fictionmags] Variant Spicies – a new can of worms

Reply-To: fictionmags@yahoogroups.com

Thanks to the intervention of chum Curt P., I have acquired a batch of PEAPS mailings from the early 1990s and will be indexing/describing these to the list in due course (i.e. some timein the next 20 years). Much of the material has been overtaken by events, but one article caught my eye as it related to my current main project (the Crime Fiction Index) and contained some information that was new to me. Sadly it also opens a whole can of worms so I was hoping the chums might be able to help me out.

The article is “Starred and Unstarred”, in three parts, by Glenn Lord, Dan Gobbett, Jerry Page & Jerry Burge. This article discusses the censorship that occurred in some issues of the SPICY pulps during the late 1930s. I’m sure most chums are aware of this but, just in case not, the basic story is that, for a while around 1935-1937, each of the Trojan SPICY titles (ADVENTURE, DETECTIVE, MYSTERY & WESTERN) appeared in “starred” and “unstarred” versions. The “starred” versions are toned down / censored both in terms of the illustrations and of the text. So far, so familiar, but Glenn Lord’s part of the article revealed something I had not heard of before – that in some of the starred issues, stories were not only censored but were also, at times, presented in a different order (not too exciting) or even dropped completely and replaced by other stories! There are therefore an indeterminate number of issues of these magazines which exist in two versions which actually have different contents (Glenn lists three issues of SPICY DETECTIVE and five of SPICY ADVENTURE with different contents and Page/Burge illustrate the ToCs from the two versions of one issue of SPICY DETECTIVE with the contents shuffled, but each suspects there are more issues as yet unrecorded). Needless to say I am extremely interested in trying to pin this down (for DETECTIVE and MYSTERY at least) for the Crime Fiction Index, not least to sort out whether the issue lists I have are for the starred or unstarred versions (or a mixture of both). I’ve e-mailed Glenn to see what information he can supply but, meanwhile, I’d love to hear from any chums who have copies of any of these pulps (or information on the variations).

Regards, Phil S-P.

This email was included as a file named “spciy note.txt” in an 80.5GB torrent of pulp-related material that has the unique torrent hash “ba32ca44c77c95c876272510ca8099e1fdda3408”. (Verbum sapienti sat est.) According to the same Phil S-P’s Fiction Mag Index, all three parts of the Starred And Unstarred article appeared in the April 1990 issue of Spicy Armadillo Stories, which sadly but unsurprisingly does not appear to be readily available on the web.

See also: REH Splashes the “Spicys” — Part V by Damon C. Sasser:

Hoping to quell some of the criticism coming from moral squads and local governments that were on the warpath to clean-up the sexual titillation prevalent in the spicys, other pulp titles and comic books, Donenfeld and his editors embarked in 1936 on a mission of self-censorship. The company began creating two versions of three of their four Spicy magazines (for some unknown reason, a censored version of Spicy Mystery was not done), each version was marked with a five point star on the cover near that issue’s month. A boxed star meant a cleaned-up version of the magazine, while no star or an un-boxed star indicated the spicy version. In the tamer version, the text was less spicy and the women’s “charms” more concealed. The self-censorship effort was stopped at the end of 1937.

But what determined where the censored, boxed star version was sold? Was it created for the Bible Belt and more conservative states? Was the censoring done to appease the Post Office? But were subscriptions actually sold? (The magazines had no subscription information in them.) Why were the dual issues only restricted to 1936 and 1937? Why was Spicy Mystery, the most notorious of the Spicy line, spared from being censored? Due to the passage of time and lack of surviving business records, we will likely never know the answers to these questions.

Appendix E: Will Murray’s Informal History of the Spicy Pulps

Bacchus here reproduces for our benefit a longish historical article, most of which I shall run “below the fold” because of its length.

In March of 1984 editor Robert M. Price announced the first issue of Risque Stories, explaining:

A special favorite among pulp magazine fans is the “spicy” magazine, a type of pulp that offered all the familiar varieties of pulp fiction (detective, horror, adventure, etc.) but with a special flare: a mildly titillating sexuality that seems naive and even corny by modern standards. Pulp fiction fanciers enjoy these stories with a kind of post-critical relish that half enters into the spirit of the thing, and half chuckles at it. It is in this spirit of pulp nostalgia that we invite you to re-live the good old days in the pages of this first issue of Risque Stories, a revival of and a tribute to the spicy magazines of yesteryear.

The Internet Archive has that issue, and in it… well, let Price introduce the article:

For those who’d like to know more about the sexy tradition in pulpdom, we present pulp scholar Will Murray’s informative “An Informal History of the Spicy Pulps.”

Here’s the Will Murray article:

An Informal History of the Spicy Pulps

by Will Murray

It’s ironic that during the so-called “Roaring Twenties,” the pulp magazine industry remained fairly sedentary, dispensing for the most part millions of copies of traditional adventure, western, detective and love stories. But once the Depression laid its cold hand on the nation, the industry responded with experimental titles, new cross-genres and a willingness to sensationalize covers and stories to the point of luridness.

So it was that in the spring of 1934, the “Spicies” first appeared. It began with a single title. Spicy Detective Stories, dated April. Although the first issue, it was called Vol. 1, Number 2 on the contents page. The somewhat racy cover depicted a scene from Jon Le Baron’s “The Love Nest Murder.” The rest of the contents consisted of similar short stories by a variety of authors, both real and spurious:

“The Perfumed Clue” by Norman A. Daniels

“Impersonator” by Alvin Gray

“Redouble” by Jane Thomas

“Murder in the Chorus” by Leslie Skate

“The Kiss Thief” by John Bard

“The Shanghai Jester” by Robert Leslie Bellem

“Death Takes a Cruise” by Eric L. Schwartz

“Sauce for the Gander” by Byrne Home

Of these names, only Norman A. Daniels and Robert Leslie Bellem are known to be the actual names of the writers. (Eric L. Schwartz, in fact, was a woman — Esther L. Schwartz.) Daniels wrote sporadically for the Spicies, but Bellem — who may also have been “Leslie Skate” — became the quintessential Spicy author. He wrote for them continually until the company ceased to publish. He was so prolific that while his byline appeared often, scores if not hundreds of his stories appeared in these magazines under assorted pen and house names.

With the June 1934 Spicy Detective Stories, Bellem introduced his immortal Hollywood private detective, Dan Turner. He became the star of Spicy Detective, and later spun off into a magazine of his own. Turner racked up about 300 adventures over the years.

The company that published this first Spicy was initially called Modern Publications. Nominally based in Delaware for tax and possibly censorship reasons, their editorial offices were at Park Place in New York. Later, the company would be called, with blank-faced humor, Culture Publications, and its offices relocated to Lexington Avenue.

The people behind the Spicies are a shadowy group. A man named Frank Armer, who had been involved in a number of earlier pulp ventures as editor or publisher, was one of the big wheels behind the scenes. Also involved was Henry Donenfeld, and a host of his relatives. The Donenfeld family seems to have been the financial mainstay of the Culture line, and there are dark rumors circulating which say the Spicy titles were bankrolled by money earned through certain illicit activities during Prohibition. Supposedly, publishing pulps was a way to “launder” such money. In later years, the Donenfelds became responsible for the explosion of comic book heroes when they brought out Superman and Batman. The first Spicy editor was a man named Laurence Cadman.

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact beginnings of the Armer/Donenfeld publishing empire. Although Spicy Detective Stories was the first of the Spicy line, it was not the first magazine to use that buzzword for sex in its title. The King Publishing Company (later D. M. Publishing) started their Spicy Stories in December 1928. It featured straight sexy stories with no genre affiliations, and was no different from the other sexy magazines of the time, like Pep and Venus. It’s not clear if the Culture group had anything to do with Spicy Stories. Only a few months before Spicy Detective started, the D. M. Publishing Company launched Super-Detective Stories, which Frank Armer edited. It was short-lived, and its link with the ture, if any, is problematic. [sic – “link with the Culture group”?] (D. M., by the way, was another Delaware corporation. ) >[?

In any event, it was during the summer of 1934 that the Spicy explosion took place. Five companion titles were created, all cover-dated July. They were Spicy Adventure Stories, Spicy Mystery Stories, Snappy Adventure Stories, Snappy Detective Stories and snappy Mystery Stories. If the Snappies differed from the Spicies to any noticeable degree, it is not evident fifty years later. In any case, they did not enjoy the long life visited upon the Spicies.

It might be difficult for a modern reader used to explicit sex in fiction of all types to appreciate the innovative nature of the Spicy line. But until Culture Publications, pulp fiction was largely asexual. Some pulps, like Adventure, took this to extremes. No females of any consequence graced its masculine pages. Love interest may have appeared in certain kinds of stories, but it was chaste stuff. Sex stories certainly existed in a number of magazines which were not exactly pulps, being thinner and of larger dimensions. But these, like the aforementioned Pep and others, were devoted to the misadventures of opposite sexes during their respective meeting rituals. It was boy-meets-girl, boy-loses-girl, etc, with some mild titillation thrown in. Light-hearted stuff. Today, it could only be called “naughty”. In fact. Culture’s slant has been described as wilder than Breezy Stories yet mild- er than Pep.

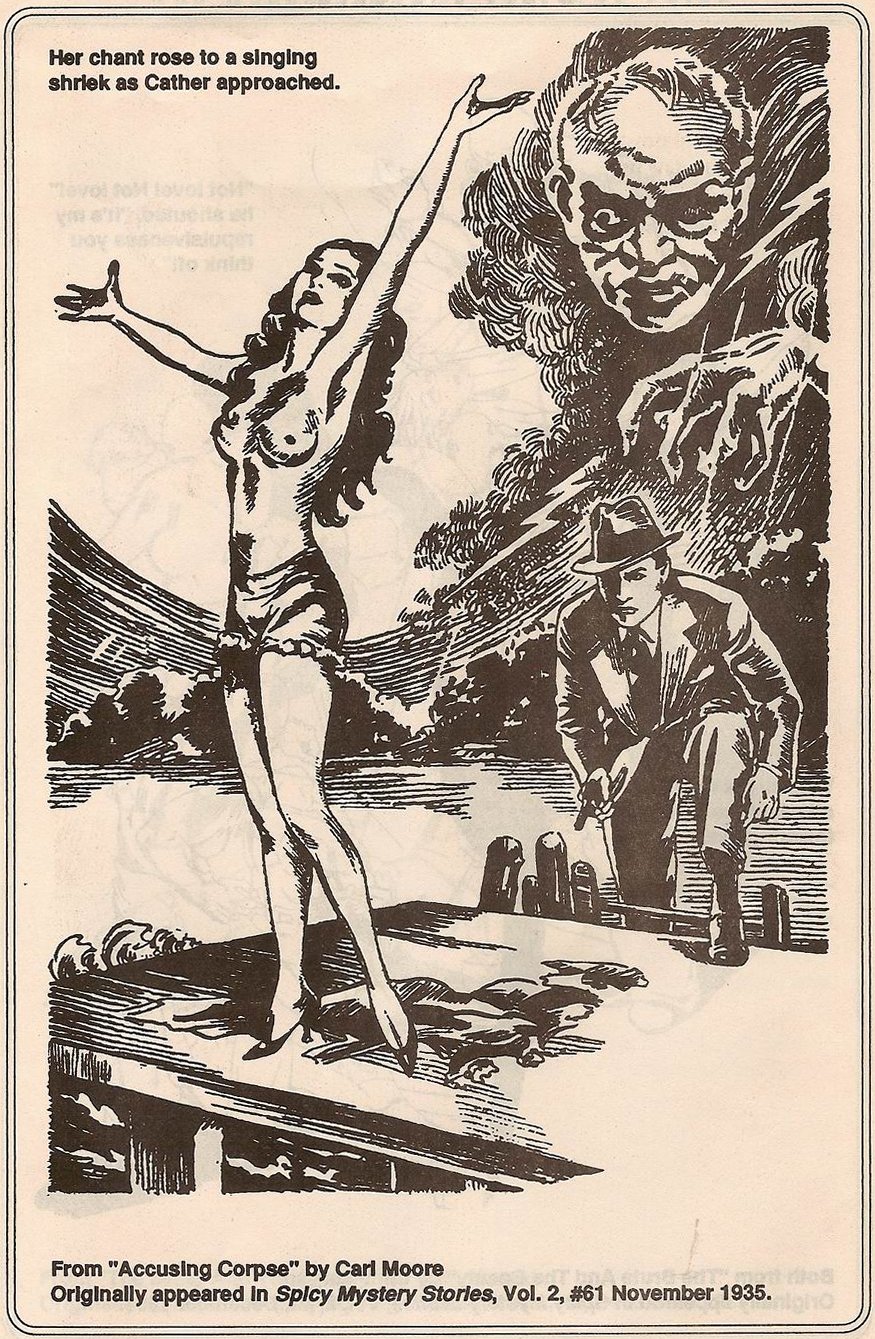

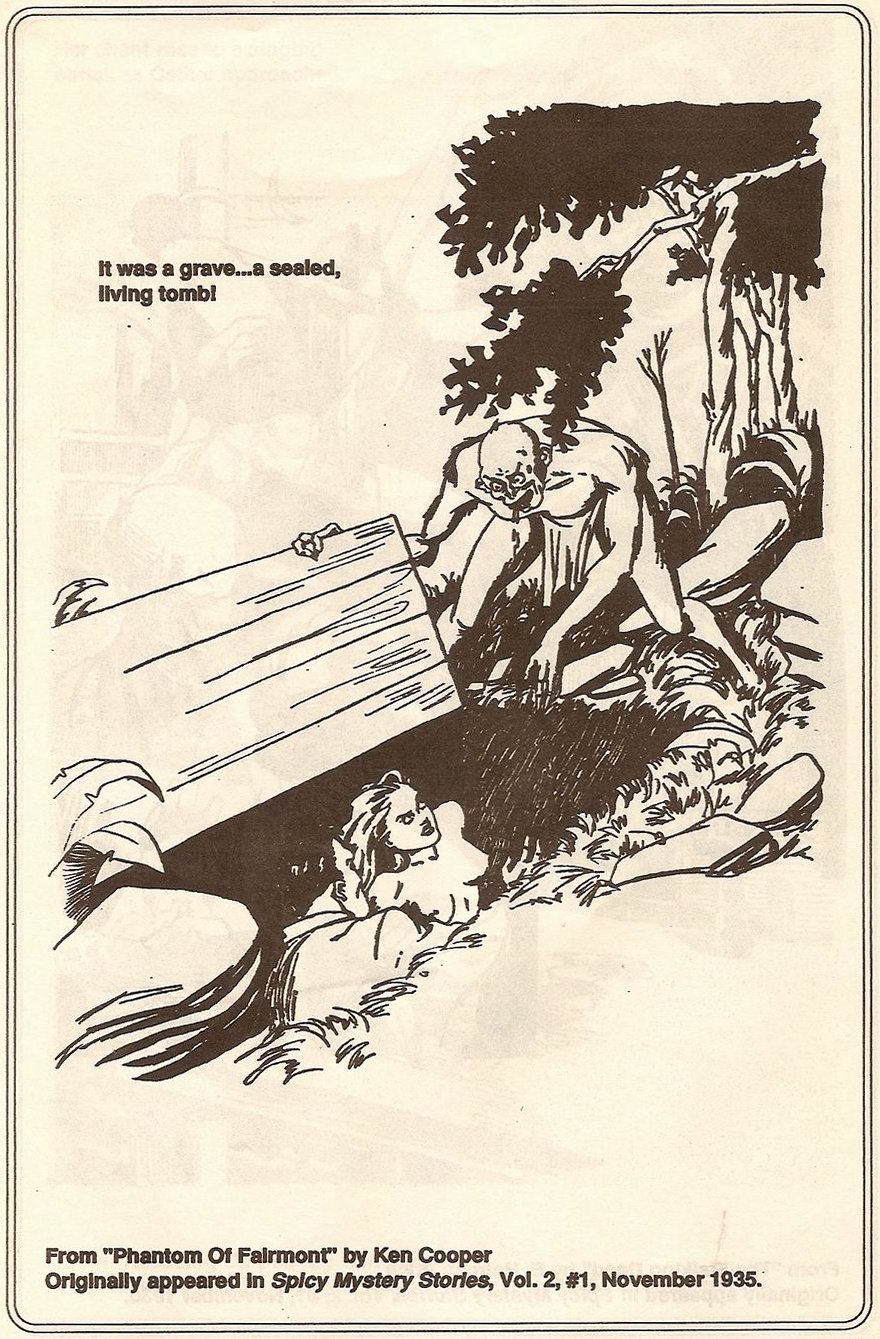

Culture Publications took the harmless sex story and grafted it onto the red-blooded pulp genres of the day. Spicy Detective Stories featured hardboiled dicks — so to speak — involved in the seamier side of their profession. Spicy Adventure Stories took the sex story around the world to exotic locales where American — the heroes of the Spicies were always Americans — explorers and adventurers rescued half-nude white girls from various vicious ethnics and manfully, if seldom successfully, attempted to resist the charms of a luscious assortment of conniving foreign temptresses. Spicy Mystery Stories had a weird flavor. The tales revolved around ghostly or sinister manifestations, which were always explained rationally.

It was a genuine revolution which, while imitated, was never done with as much style and verve as Culture Publications managed to invest in their line.

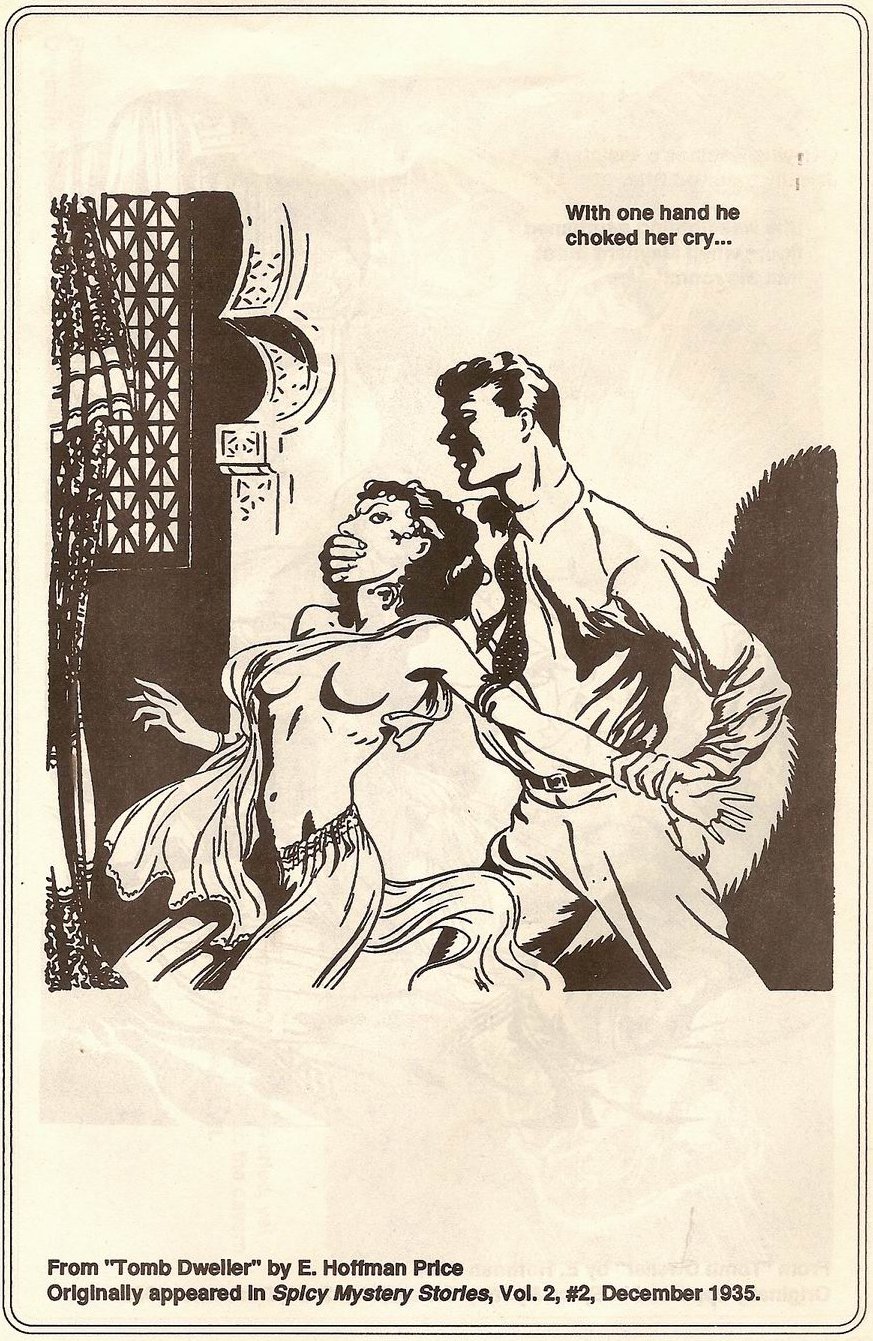

The key to the Spicies was their clean, almost wholesome look— which was there even when the cover depicted a malignant dwarf shooting arrows at a scantily-clad girl tied to a giant bull’s-eye. The man most responsible for this look was cover artist H. J. Ward, who painted his girls in attractive, girl-next-door strokes and gave them enough clothes to preserve their decency without minimizing their charm — or “charms,” as the authors were wont to call their endowments. Accidentally or by design, the Spicy approach to female nudity had much the same appeal which made the early Playboy famous. Regardless of the pose or situation — and some were pretty wild — the Spicy Girl always looked wholesome, virginal, yet tantalizing.

Other artists, like H. Parkhurst, also painted Spicy covers, but Ward was the most used, best remembered, and his style was clearly the Spicy house style. Interior art was often the same, but more daring. Actual nudity was shown, but with details left obscured. Parkhurst did a number of interior pieces as well, as did Paul H. H. Stone and Max Plaisted. While most artists didn’t sign their work, one who did was Joseph Sokoli, whose sharp line drawings “spiced” most issues. (Later, he did abstract covers for the line, too.) Culture relied heavily on its artists, and even the shortest stories were heavily illustrated and set in large, very readable type.

The Spicy titles had a certain elegance that was almost, but not quite, at odds with its steamy subject matter. That may not have been evident in the Thirties, when the Legion of Decency was created (in the very same year the Spicies debuted!) to police movies, but today, when mainstream fiction is more explicit than the Culture editors ever dreamed of being, the content of most issues seems quaint, almost innocent.

Well, not quite. There was a certain amount of hot sex, sadism, illicit relationships, rape and questionable attitudes toward male/female coexistence. Yet when it came down to the raw facts, the Spicies blushed and turned away. Anatomical details eluded the authors. They enjoyed describing “swelling breasts” and “shapely thighs” and “creamy (or alabaster) skin,” but never described nipples or breathed a word about female pubic hair and its secrets. Men were not described in sexual terms at all. And when the foreplay was over, the paragraph would melt into ellipses . . . and the reader’s over-heated imagination was on its own.

The sexual angles, overplayed on the covers and interior art, were not as big a part of the stories as the packaging promised. True, sex was a preoccupation of most of the casts, but often nudity alone was the result. One Spicy contributor, Norman A. Daniels, claimed that whenever his other markets rejected a story, he just threw in some passing remarks about shapely feminine bodies and sent it to the appropriate Spicy title. Other writers report using this tactic, too.

The Spicy line, by 1936, included a new title, Spicy Western Stories. It was the last of the four main Spicy titles, yet it may have been one of the most logical ideas. Back in the Twenties, other publishers had successfully combined the love and western themes (the two best-selling pulp genres, by the way) with Ranch Romances and a host of very popular imitators.

But the Spicies were not all Culture-published. They inaugurated a related line under the Trojan Publishing Company name. The inspiration for the firm’s name is open to speculation. Its first title was Super Love Stories in 1934. The Trojan arm of Culture Publications was its more legitimate expression. Trojan eschewed salaciousness and published mainstream pulps. They were sold from the same racks that featured other pulps. Whether or not the Spicies were sold on newsstands or under-the-counter depends on who you talk to — but actually this may have varied according to where they were sold. It’s likely Trojan was incorporated as a separate entity to protect that line in case obscenity suits or censorship problems wiped out the Culture titles.

Trojan published a diverse group of magazines, including The Lone Ranger (based on the radio hero), Romantic Detective, and Private Detective Stories, where Robert Leslie Bellem’s Dan Turner found himself a new home, and prospered. In 1940, Frank Armer revived his old Super-Detective title, this time with a Doc Savage-type hero named Jim Anthony leading each issue and, oddly enough, during the first year, with a number of science fiction stories in the back pages. Later, it became a straight detective magazine, and Jim Anthony was dropped.

Bellem and his friend W. T. Ballard wrote the Anthony stories under the John Grange house name. While sex was not a staple of the Trojans, what was euphemistically termed “girl interest” was. Attractive young women were prominently displayed on most Trojan covers, often with a great deal of attention focused on nyloned legs and the “damsel in distress” motif. But this was just window dressing.

The exact relationship between the Culture and Trojan groups is deliberately unclear. In 1938, self-appointed censors began to go after the more conspicuous sex pulps. The heat reached the Culture line, which began to cool the “heat” in its pages. The old tepid descriptions of foreplay were dropped, but the covers remained as racy as before. Culture did this reluctantly, but caved in when the Post Office threatened to remove its second-class mailing privileges, without which subscription copies could not be mailed. A year later, in 1939, it was announced that Culture Publications had “changed owners” and severed its relations with what was called “Frank Armer’s New York group” — i.e., Trojan. But this may have been only a dodge, as later developments suggest. Coincidentally or not, D. M. Publishing (still publishing the old Spicy Stories) went out of business at this time.

in any case. Culture and Trojan continued publishing, sharing essentially the same stable of writers and artists, and a distinctly joint “house look.” But who were the Spicy writers?

Well, many of them, like Norman A. Daniels, were regular pulp hacks who submitted to the Spicies when the spirit moved them. Culture paid only ½ to 1 ¢ per word, but was a wide open market with a reputation for paying quickly. The bolder of these writers wrote for the Spicies under their own names. E. Hoffmann Price was one of these brave souls. (An interesting sidelight to Price’s Spicy work was two stories Clark Ashton Smith gave him after Smith found them unsalable. In 1940, Price rewrote them for Spicy Mystery. The first, “House of the Monoceros,” appeared in the February 1941 issue as “The Old Gods Eat,” while the second story’s fate is unknown. It was titled “Dawn of Discord.” Naturally, they were greatly changed in the telling.) John A. Saxon and Ken Cooper (who may or may not have also written as Edgar L. Cooper) were two of Culture’s regulars. Lars Anderson was almost the real name of Alan Ritner Anderson. Justin Case, one of the Spicy “house names,” was recently revealed to be Hugh B. Cave— all by himself!

Many of these writers specialized in sex stories for various publishers, and their bylines never appeared outside this field. One, a woman named Thelma B. Ellis, wrote for Culture under her own name, a female pen name and two male pen names — all now forgotten.

Others, like Laurence Donovan, started off in the Spicies, went on to write Doc Savage, the Phantom, the Whisperer and other pulp heroes, then ended up back in the Spicies. George A. MacDonald was another Phantom author who worked for Trojan. Mystery writer Wyatt Blassingame did Spicies as William B. Rainey. W. T. Ballard used the names Clive Trent and Isaac Walton — but whether these were his exclusive bylines or merely ubiquitous house names is unclear. Of course, Robert E. Howard did his share of these stories as Sam Walser. Roger Torrey — a real author — did a lot of work for Private Detective. Science fiction scribes like Henry Kuttner, Ray Cummings and Ralph Milne Farley (really ex-senator Roger Sherman Hoar) are known contributors — even if their bylines are not.

But the king of them all was the mild-mannered bespectacled Robert Leslie Bellem. Bellem did not fear to sign his own name to his stories — but he did so many that other bylines came into play to an amazing degree. His favorite Spicy bylines were Ellery Watson Calder, Harley L. Court, and Jerome Severs Perry; these were personal pen names. But he also wrote as Randolph Barr, Rex Daly, William Decatur, Walton Grey, John Grange, Paul Hanna, R. T. Maynard, Henry Phelps, Don Traver, Stan Warner, Hamilton Washburn, John Wayne (!) and Harcourt Weems. Exactly how many of these were house names may be beyond human rediscovery, but known ones include William Decatur, R. T. Maynard, and Max Neilson.

Bellem wrote in a glib, super-colloquial style, especially in his Dan Turner stories, where Turner, who narrated his own adventures, liked to describe female breasts by such code words as “pretty-pretties,” “tiddly-winks,” “bon-bons” and “whatchacallems.” It may be a measure of the Spicy audience’s mentality not only that Turner’s adventures ran for years in Spicy Detective and Private Detective, but that in 1943, Culture-Trojan began reprinting the older stories in Hollywood Detective, usually three to an issue. The publisher was given as Arrow Publications, a new arm nominally headquartered in Springfield, Massachusetts.

The reason for creating Arrow Publications was that the Culture line was disbanded (ostensibly, at any rate) in 1942. Official pressure had continued against the Spicies. New York’s mayor Fiorello La Guardia prevented the titles from being sold in Manhattan unless the covers were removed.

Culture realized that they’d run their course. They’d established hot titles in the big four pulp genres (only a Spicy Science Fiction Stories was overlooked — but then Spicy Adventure and Spicy Mystery did a lot of SF stories and covers in the early forties), diversified enough to cover their losses in any situation, and sales had slacked off. Frequently, older stories would be reprinted under new house bylines. So they finally killed off the Spicies.

But that wasn’t the end, by any means. At the beginning of 1943, Trojan started four new titles. Speed Adventure, Speed Detective, Speed Mystery and Speed Western Stories. Most were cover-dated January 1943. They weren’t as racy as the Spicies, but in their own way they were “fast.” Under the Arrow line, milder titles were established, including Leading Love and Western Love. Trojan came out with Leading Western, Blazing Western and Amour.

The Speed titles were edited by two men who had been with Trojan since the thirties, Wilton Matthews and Kenneth Hutchinson. They were responsible for the increasing use of reprints in the Spicy titles. Apparently, some of these Spicy stories were reprinted in the Speed titles, because in June of 1947 it was announced that Matthews and Hutchinson had been arrested and convicted of “check-juggling.” They were sentenced to two to four years apiece. It came out that they had engineered a racked as sweet as any published in the pages of Spicy Detective. They would “purchase” stories, publish them as new and pocket the checks, when actually they were passing off reprints culled from the back pages of their own titles. Because the Spicies bought all rights, and because this canny duo always changed the bylines when they reprinted, the original authors had nothing to complain about even if they realized their stories had appeared again. (This is why some Robert E. Howard Spicy Adventure stories were reprinted under various house names.) Apparently one of these two masterminds pretended he wrote these “new” stories. In any event, they were caught and put away. As a result, the Arrow, Trojan and Speed lines were consolidated.

It would be poetic if the whole Culture/Trojan story had ended on such a deliciously sordid note, but it didn’t. Many titles continued, and in 1948, a year after the “consolidation,” Frank Armer officially stated he had only four active titles left — Hollywood Detective, Private Detective, Fighting Western and Leading Western. The new editor was listed as Adolphe Barreaux. Supposedly the Donenfeld family divested themselves of their Spicy interests in the wake of their great comic book success.

Yet despite these claims, other titles continued. It seems that some of the Speed titles and Super-Detective continued until at least 1949 or 1950. Perhaps another outfit bought them out. Certainly by no later than 1951, if then, the whole operation had folded, its offices (wherever they were by then) closed, and its authors scattered to other pursuits (Bellem went to Hollywood to script The Lone Ranger and Superman). Even Dan Turner retired. The Spicies had seen their day in the sun — or was it their evening under the moon?

Although Culture Publications had taken a great deal of heat over the years, by 1950 standards they were already passe even in their most extreme form. The new and burgeoning paperback industry pushed the limits of propriety leagues beyond anything Armer envisioned; they dealt directly with themes like interracial love, homosexuality and other once-taboos, leaving the entire Culture/Trojan approach to sex stories in the dust and rendering the very term “spicy” antique.

The fact is that the Spicies were extremely tame. Where some of the more lurid imitators plunged head- first into sexual sadism combined with horror, Culture soft-pedalled such approaches. Competing titles like Horror Stories and Uncanny Tales regularly cover-featured scenes of indescribable (and sometimes inadvertently hilarious) torture with titles like “Daughters of Lusting Torment,” “The Monster Wants More Than a Mate” and “The Claw Will Come to Caress Me.” Culture covers were restrained by comparison, and their titles seldom had sexual connotations. Most of them, like “She from Beyond, ” “Ghosts in Her Eyes” and “Dance of Damballa,” could have appeared in almost any pulp magazine. This is not to whitewash the Spicies; their slant was unabashedly erotic, their purpose to titillate. It’s just that they were so immature about it. When Armer started operations back in 1934, he instructed his writers that “Our stories border on the risque, the situations may be compromising and passionate but there must be no ac-tual ‘consummation of love.'” Even the way he describes it today seems quaint and vaguely prudish.

In retrospect, one of the features carried by every Spicy seems to speak eloquently of the playful element that characterized them. Each title ran its own serialized comic strip. It started with “Sally the Sleuth,” a four-page feature in which the blonde detective invariably found herself in distress and undress. This, appeared in Spicy Detective and was: signed, if memory serves, “Adolpha Barreaux.” Spicy Adventure featured a female Flash Gordon named Diana Daw, ostensibly by Clayton Maxwell. Spicy Mystery tried “The Adventure of Olga Mesmer,” the Girl with the X-Ray Eyes (creator Watt Dell explained that her strange powers, “dormant” during her childhood, “burst into light once she is aroused, and Olga embarks upon a remarkable career”) but replaced her with another distaff spacegirl, Vera Ra, by the same writer. The sexual content of these strips was limited to the heroines stripping to their underwear when the going got rough. One gets the impression these strips were there for the edification of the pre-pubescent. And speaking of pre-pubescent types, adventurer Dan Turner got his own comic strip in Hollywood Detective. Naturally, Bellem did the writing.

The Spicies are long dead now. No vestige of the former pulp empire exists, and there are no records to reveal the secrets behind such frequent but mysterious Spicy bylines as Lew Merrill, Robert A. Garron, Morgan La Fay, C. A. M. Donne and Cliff Ferris. Only the magazines remain, and not many of these. What does survive of those once-mighty print runs belongs in the domain of the serious pulp collector who may collect them for nostalgia, for the lush H. J. Ward covers or even for their faintly risque charm — but certainly not for their titillation value. The world outgrew the big, bad Spicies a long, long time ago.

Appendix F: Canadian Editions of the Pulps

According to The Library and Archives of Canada, the War Exchange Conservation Act of 1941 banned the importation of US pulp magazines to preserve Canada’s balance of trade with the United States. A brief but vibrant Canadian pulp magazine industry was the result:

The year 1940 was one of great change in Canada. A constitutional amendment allowed the government to introduce and adopt the Unemployment Insurance Act. Parliament passed the controversial National Resources Mobilization Act authorizing home defense conscription for 30 days, a term that over time stretched to cover the duration of the Second World War. In Quebec, women won the right to vote.

And, with the passing of the War Exchange Conservation Act, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King became the unwitting father of the Canadian pulp magazine industry.

According to Carolyn Strange and Tina Loo, the War Exchange Conservation Act was designed to preserve Canada’s balance of trade with the United States. To preserve this balance, Canada banned the import of a broad range of nonessential items from the U.S., including such luxury items and diversions as cocoa paste, champagne and pictoral postcards. It also targeted what had become for many people not a luxury, but an essential distraction from the harsh realities of everyday life: the pulps. The language of the act specifically prohibited the import of any periodical publications featuring “detective, sex, western and alleged true or confession stories.”

Detectives. Sex. Westerns. Confession stories. These were topics that sold magazines, and Canadian publishers knew it. People would still want their weekly fix of grisly murder, winking pin-up girls, thundering hooves and vicarious heartbreak; if the Americans could no longer supply it, someone else would have to.

As the December 1940 issue of the industry magazine Canadian Printer and Publisher put it: “Certain branches of the printing industry stand to benefit as a result of the measures announced in the House of Commons on Dec. 2 by Hon. J. L. Ilsley, Minister of Finance. Included in the long list of prohibited imports from non-sterling countries, principally the United States, are certain kinds of periodical publications such as those classified as detective, sex, western and confession stories.”

There were those words again. Detectives. Sex. Westerns. Confession stories. Add a smattering of other genres (science fiction, horror and the “northerns” — adventures that transposed the action of the western to Canada’s far north and swapped cowboys for Mounties), and you had what would become the stock-in-trade for Canadian pulp publishers.

In the beginning, Canadian publishers relied on submissions from U.S. authors, or even pirated copies of stories published in U.S. magazines. After all, Canadian audiences would recognize these authors, many of whom had developed a loyal following during the period when American pulps were readily available. The readers knew which writers penned the goriest murders, the most risqué love affairs and the most bloodcurdling horror stories.

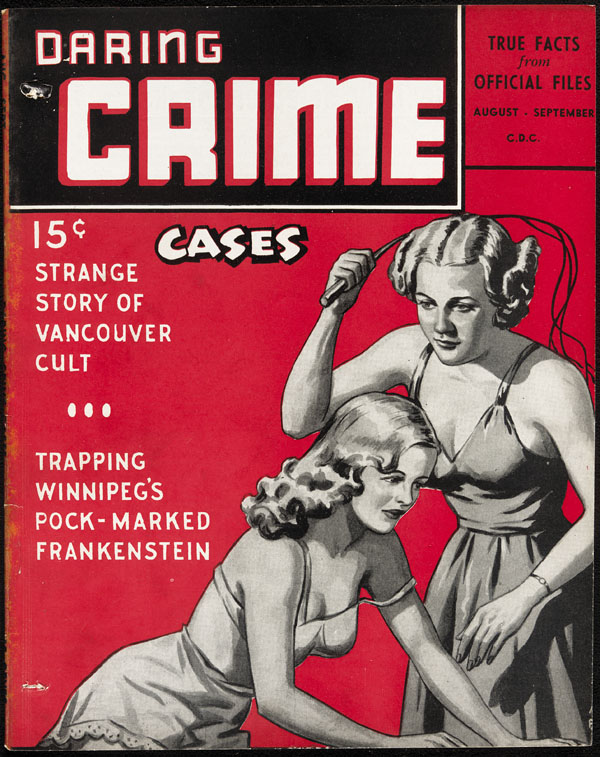

But the pace of publishing demanded more and more stories. In English Canada, most titles were published monthly or bimonthly, and could contain as many as ten stories apiece. To keep up with the need for content, pulp publishers increasingly solicited stories from Canadian writers and accepted stories set in Canada. Suddenly, in a medium once dominated by American stories, characters and settings, reader became enthralled by such tales as “The Strange Story of Vancouver Cult” or “Trapping Winnipeg’s Pock-Marked Frankenstein.”

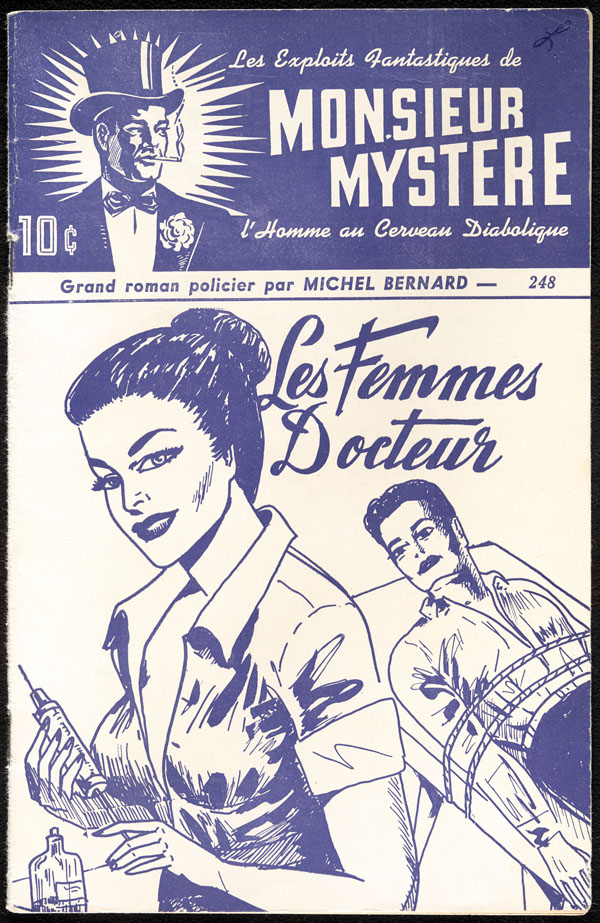

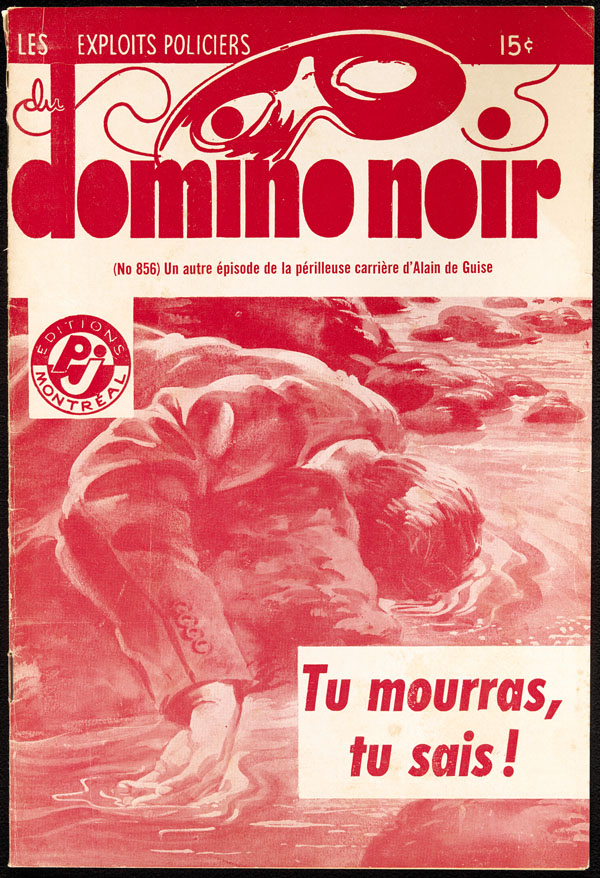

In Quebec, where many titles were published weekly, a pattern of publishers relying almost entirely on homegrown talent emerged, in addition to reprints or serializations of older stories by European authors. Sources of French-language writing were limited. Few American writers would have had a sufficient command of either the French language or Quebec culture to create a story for Les exploits fantastiques de Monsieur Mystère, or Les exploits policiers du Domino Noir.

Canadians were writing. Canadians were publishing. Canadians were reading. The Canadian pulp publishing industry was in its golden age.

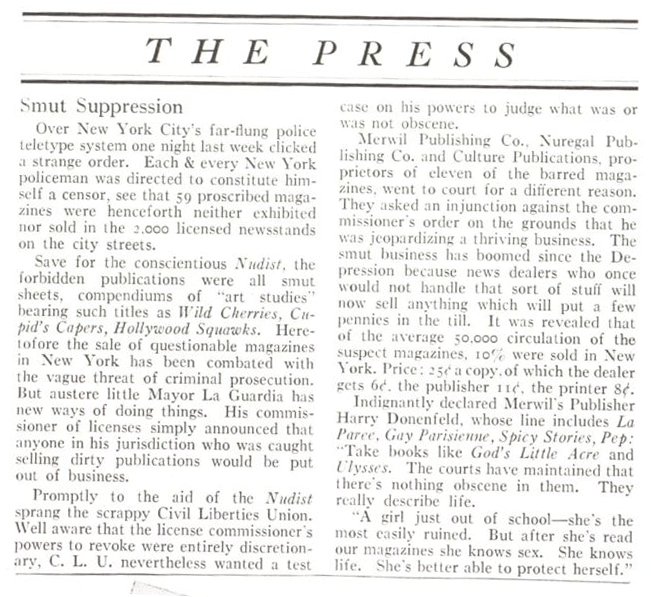

Appendix G: Time Magazine on “Smut Suppression”

This 1934 primary source news article on censorship of pulp magazines (including the famous “Spicys”) in New York City makes several useful points:

- The many stories of Mayor La Guardia angrily discovering a “Spicy” title on a news stand 1942 are naive to whatever extent they are intended to suggest that he was actually surprised by the existence of salacious pulps in his city. By that point he had been fighting them for at least six years, so by 1942 he was probably play-acting his surprise if not his anger.

- The story estimates that “New York” (city or state not specified) is responsible for only 10% of the business in risque pulps in 1934, which undercuts the theory that New York City censorship could have directly or primarily have caused the demise of the shudder pulp trade.

- Smutty trends in the pulp business were supported, the story suggests, by hungry news stand operators post depression, raising the implication that the return of prosperity might have contributed to the decline of the smuttiest part of the trade.

“Smut Suppression”

Time Magazine

March 12, 1934Over New York City’s far-flung police teletype system one night last week clicked a strange order. Each & every New York policeman was directed to constitute himself a censor, see that 59 proscribed magazines were henceforth neither exhibited nor sold in the 2.000 licensed newsstands on the city streets.

Save for the conscientious Nudist, the forbidden publications were all smut sheets, compendiums of “art studies” bearing such titles as Wild Cherries, Cupid’s Capers, Hollywood Squawks. Heretofore the sale of questionable magazines in New York has been combated with the vague threat of criminal prosecution. But austere little Mayor La Guardiahas new ways of doing things. His commissioner of licenses simply announced that anyone in his jurisdiction who was caught selling dirty publications would be put out of business.

Promptly to the aid of the Nudist came the scrappy Civil Liberties Union. Well aware that the license comissioner’s powers to revoke were entirely discretionary, C.L.U. nevertheless wanted a test case on his powers to judge what was or was not obscene.