Bacchus’s writeup on shudder pulps continues

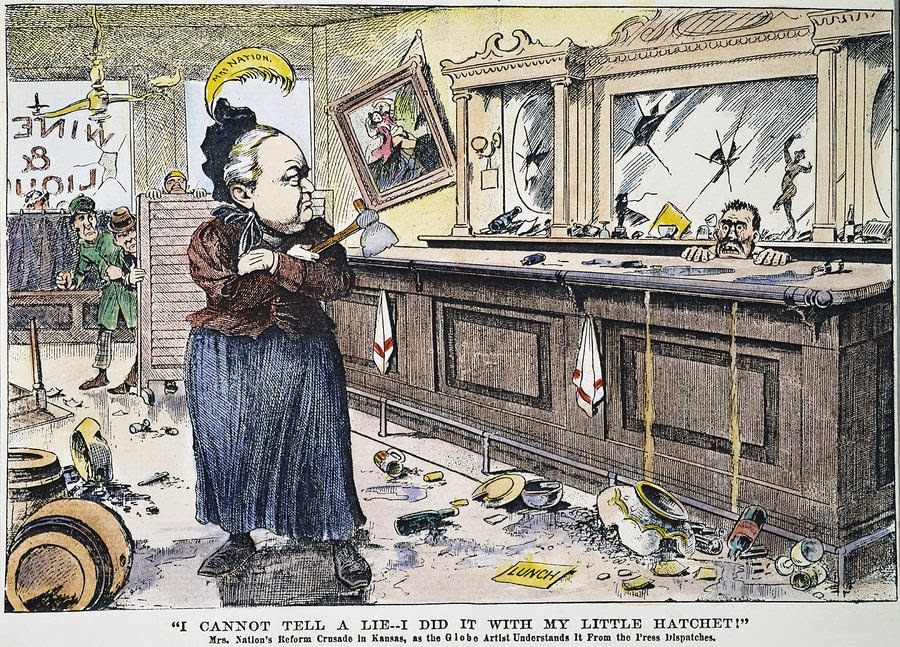

It can be hard, sometimes, to determine whether a particular bit of social pressure is censorship proper (an exercise of government suppression) or “merely” public censure of a particularly robust but more informal kind. It’s the difference between Carrie Nation’s hatchet-wielding saloon-smashers and the formal Act of Prohibition of 1918, if you will; the distinction is strong in theory and rather less important in practice. There was definitely some of both sorts deployed against the most scandalous of the pulps of the late 1930s, and given the extra-legal impulses of machine politicians of the era, clear lines will not always possible to draw.

The most notable — and most often cited — bit of anti-shudder-pulp fulmination and agitation must surely be the nine pages of derisive criticism vomited forth by Bruce Henry in the conservative magazine The American Mercury in April of 1938 under the title “Horror On The Newsstands”. It’s worth reading the whole thing, but the first paragraph alone will set you on the road to understanding the tone:

This month, as every month, some 1,580,000 copies of terror magazines, known to the trade as “the shudder group”, will be sold throughout the nation. Between their frankly lascivious front covers and their advertisements for masculine pep tablets in the rear, these titillating contributions to American belles lettres will contain enough illustrated sex perversion to give Krafft-Ebing the unholy jitters. Never, in fact, since the popularity of the Marquis de Sade, has civilzation seen such a plethora of Frankensteinian literature as is now circulating in this land of peace and good-will. France may have her Grand Guignol, Spain her wartime atrocities, but only in America is it possible for the masses to go in for vicarious Torquemadian exercises through the simple expedient of patronizing the nearest newsstand.

Interestingly, though Henry disapproves of the shudder pulps at great and vituperative length, he nowhere calls for their censorship. It is not inconceivable that The American Mercury’s own 1927 brush with obscenity prosecution explains this restraint; editor H.L. Mencken was tried and acquitted, and an issue of his magazine declared unmailable by the U.S. Postal Service. No, Henry’s article is literary criticism at its most dismissive, but it’s no call for censorship.

Other hints of public disapproval also find their way into the pulp-aficionado accounts of shudder-pulp history. For instance, in Pulp Horrors Of The Dirty Thirties (an essay found in The Pulpster, excerpted here) Don Hutchison writes that in “the early 1940s” “there developed a public rejection of the permissiveness and thrill-seeking of the thirties… As shudder pulp stalwart Bruno Fischer described it “Clean-up organizations started throwing their weight around and gave editors jitters, and artists and writers were instructed to put panties and brassieres on the girls.” Sadly no context for the Bruno Fischer quote is offered.

To be continued.