Bacchus’s research continues.

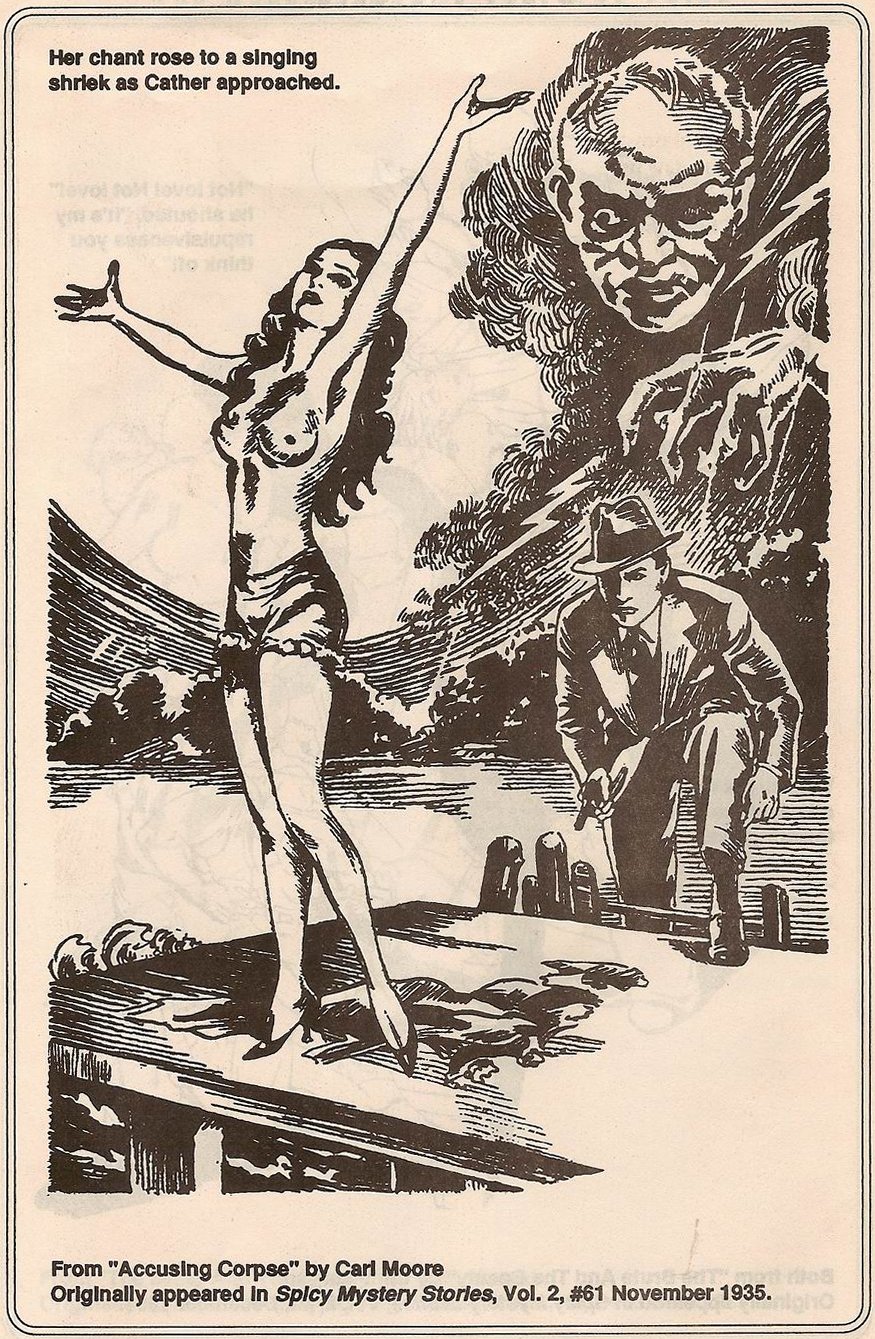

It is unclear to what extent the shudder pulps specifically were ever sold by postal subscription or relied upon mail distribution, if at all. The vituperative critic Bruce Henry suggests that they did, and he averred in his infamous 1938 critical expostulation that the horror pulps modified their artwork accordingly to cover “pelvic regions” and breasts without nipples:

“But, say mail inspectors, the illustrations must never show a completely nude wench and the pelvic region must always be obscured in some fashion. Smoke from the bubbling acid vat is usually good camouflage, as is the well-known wisp of silk. Uncovered breasts are admissible, so long as they—quaint fancy — possess no apices, as it were.”

Will Murray, in his Informal History Of The Spicy Pulps, references a specific 1938 threat from the Post Office against Culture Publication’s mailing permit. This is also the most specific reference found to the distribution of these pulps via mail subscription:

In 1938, self-appointed censors began to go after the more conspicuous sex pulps. The heat reached the Culture line, which began to cool the “heat” in its pages. The old tepid descriptions of foreplay were dropped, but the covers remained as racy as before. Culture did this reluctantly, but caved in when the Post Office threatened to remove its second-class mailing privileges, without which subscription copies could not be mailed.

Don Hutchinson goes further, in attributing the 1943 the retooling of the Spicy titles (including their renaming as Speed titles and general toning down after the infamous La Guardia explosion of 1942) in part to “fear of losing…their U. S. postal mailing privileges.” His evidence for this is not indicated. Damon Sasser likewise cites — and likewise doesn’t gesture at any evidence for citing — postal pressure as a major factor in that same big Spicy retrenchment of 1942:

By late 1942, a full court press from all sides was on the Spicy line and Donenfeld and company were forced to take action. In addition to pressure from government officials, changes were needed keep the Post Office Department happy and protect the publisher’s coveted second class mailing rate. So, in an attempt to continue publishing these successful pulps under the harsher censorship and scrutiny, covers were toned down, as was content and interior illustrations and the entire Spicy line was renamed “Speed” to eliminate the word “Spicy.”

It is well-documented that a Catholic pressure organization called the National Organization For Decent Literatature (NODL), was founded in 1938 to keep “indecent literature” “out of the community”. Its founder, one Bishop Noll, published a cartoon illustrating his intentions in a long-running Catholic publication called “Our Sunday Visitor”. Although that cartoon has proven highly resistant to being turned up in visual form, here’s a written description:

Under the headline “Now is the Time to Act” it showed a bespectacled, boyish-looking middle-aged man — a dead-on likeness of Noll, labelled “Catholic Organizations” — and in a word balloon he said, “We cleaned up the movies, but we’ve let you parasites exist too long.” He was swishing a broom, literally cleaning up a newsstand from which anthropomorphic magazines with tiny legs and feet were scurrying away. They had titles such as Nasty News, Sexy Stuff, Photo Philth, and Cartoon Dirt.

This description is in The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America (2008) by David Hajdu; and although Hajdu does not say precisely when the cartoon was published, he implies it was shortly after NODL was founded in 1938, when shudder pulps might plausibly have been on NODL’s hit list. Per Hajdu, the list was quite literal; it was offically called (at first) “Publications Disapproved For Youth”, though Noll himself called it his “black list.” It was published monthly in NODL’s magazine The Acolyte but not made public for fear that young people “looking for something bad to read” would consult it. (NODL’s “The Acolyte” — no copies of which were found on the internet — should by no means be confused with the roughly-contemporaneous 1940s amateur mimeographed “fantasy and scientifiction” magazine of the same name, some five issues of which may be found in the Internet Archive.)

At some point, NODL began working closely with the Postmaster General (also a Catholic) who by 1943 at least was barring long lists of slightly-risque pulp magazines from the mails, or at least denying their subsidized second-class mailing permits. Moreover, by that time many publishers were “cooperating” with NODL by submitting advance copies of publications for review and making close edits at church direction to avoid trouble with NODL and the post office. A newspaper article to be discussed in a future post in this series will provide a lot of detail about the situation in 1943, although it’s too late in time to shed much light on the effect of NODL’s activities on the shudder pulps in particular and it doesn’t directly address the still-uncertain question of how important subsidized mailing privileges were to pulps in general.

Although this research did not turn up any editions of the Acolyte publication or of the NODL blacklist itself, by November 1942 the NODL banned publications list in the Acolyte is said to have grown to 190 “Magazines Disapproved by The National Organization of Decent Literature.” Such a list was still being updated and included in something called the Manual Of the N.O.D.L. (a 222-page publication) as late as 1952. With the 1942 list, NODL noted:

This list is neither complete nor permanent. Additional periodicals will be added as they are found to offend against our code… They are on our list because they offend against one or more of a five point Code adopted by the NODL. [They] glorify crime or the criminal; are predominatly “sexy”; feature illicit love; carry illustrations indecent or suggestive, and advertise wares for the prurient minded.

That the NODL/postal situation was so wretched for pulps in general by 1943 lends credence to the non-specific references in the secondary sources suggesting that the shudder pulps, too, had postal permit issues, especially after 1938 when NODL was founded. However, that same source indicates that postal service revocations of 2nd-class mailing permits did not actually begin until 1942, so the matter is uncertain.

To be continued.