Bacchus here reproduces for our benefit a longish historical article, most of which I shall run “below the fold” because of its length.

In March of 1984 editor Robert M. Price announced the first issue of Risque Stories, explaining:

A special favorite among pulp magazine fans is the “spicy” magazine, a type of pulp that offered all the familiar varieties of pulp fiction (detective, horror, adventure, etc.) but with a special flare: a mildly titillating sexuality that seems naive and even corny by modern standards. Pulp fiction fanciers enjoy these stories with a kind of post-critical relish that half enters into the spirit of the thing, and half chuckles at it. It is in this spirit of pulp nostalgia that we invite you to re-live the good old days in the pages of this first issue of Risque Stories, a revival of and a tribute to the spicy magazines of yesteryear.

The Internet Archive has that issue, and in it… well, let Price introduce the article:

For those who’d like to know more about the sexy tradition in pulpdom, we present pulp scholar Will Murray’s informative “An Informal History of the Spicy Pulps.”

Here’s the Will Murray article:

An Informal History of the Spicy Pulps

by Will Murray

It’s ironic that during the so-called “Roaring Twenties,” the pulp magazine industry remained fairly sedentary, dispensing for the most part millions of copies of traditional adventure, western, detective and love stories. But once the Depression laid its cold hand on the nation, the industry responded with experimental titles, new cross-genres and a willingness to sensationalize covers and stories to the point of luridness.

So it was that in the spring of 1934, the “Spicies” first appeared. It began with a single title. Spicy Detective Stories, dated April. Although the first issue, it was called Vol. 1, Number 2 on the contents page. The somewhat racy cover depicted a scene from Jon Le Baron’s “The Love Nest Murder.” The rest of the contents consisted of similar short stories by a variety of authors, both real and spurious:

“The Perfumed Clue” by Norman A. Daniels

“Impersonator” by Alvin Gray

“Redouble” by Jane Thomas

“Murder in the Chorus” by Leslie Skate

“The Kiss Thief” by John Bard

“The Shanghai Jester” by Robert Leslie Bellem

“Death Takes a Cruise” by Eric L. Schwartz

“Sauce for the Gander” by Byrne Home

Of these names, only Norman A. Daniels and Robert Leslie Bellem are known to be the actual names of the writers. (Eric L. Schwartz, in fact, was a woman — Esther L. Schwartz.) Daniels wrote sporadically for the Spicies, but Bellem — who may also have been “Leslie Skate” — became the quintessential Spicy author. He wrote for them continually until the company ceased to publish. He was so prolific that while his byline appeared often, scores if not hundreds of his stories appeared in these magazines under assorted pen and house names.

With the June 1934 Spicy Detective Stories, Bellem introduced his immortal Hollywood private detective, Dan Turner. He became the star of Spicy Detective, and later spun off into a magazine of his own. Turner racked up about 300 adventures over the years.

The company that published this first Spicy was initially called Modern Publications. Nominally based in Delaware for tax and possibly censorship reasons, their editorial offices were at Park Place in New York. Later, the company would be called, with blank-faced humor, Culture Publications, and its offices relocated to Lexington Avenue.

The people behind the Spicies are a shadowy group. A man named Frank Armer, who had been involved in a number of earlier pulp ventures as editor or publisher, was one of the big wheels behind the scenes. Also involved was Henry Donenfeld, and a host of his relatives. The Donenfeld family seems to have been the financial mainstay of the Culture line, and there are dark rumors circulating which say the Spicy titles were bankrolled by money earned through certain illicit activities during Prohibition. Supposedly, publishing pulps was a way to “launder” such money. In later years, the Donenfelds became responsible for the explosion of comic book heroes when they brought out Superman and Batman. The first Spicy editor was a man named Laurence Cadman.

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact beginnings of the Armer/Donenfeld publishing empire. Although Spicy Detective Stories was the first of the Spicy line, it was not the first magazine to use that buzzword for sex in its title. The King Publishing Company (later D. M. Publishing) started their Spicy Stories in December 1928. It featured straight sexy stories with no genre affiliations, and was no different from the other sexy magazines of the time, like Pep and Venus. It’s not clear if the Culture group had anything to do with Spicy Stories. Only a few months before Spicy Detective started, the D. M. Publishing Company launched Super-Detective Stories, which Frank Armer edited. It was short-lived, and its link with the ture, if any, is problematic. [sic – “link with the Culture group”?] (D. M., by the way, was another Delaware corporation. ) >[?

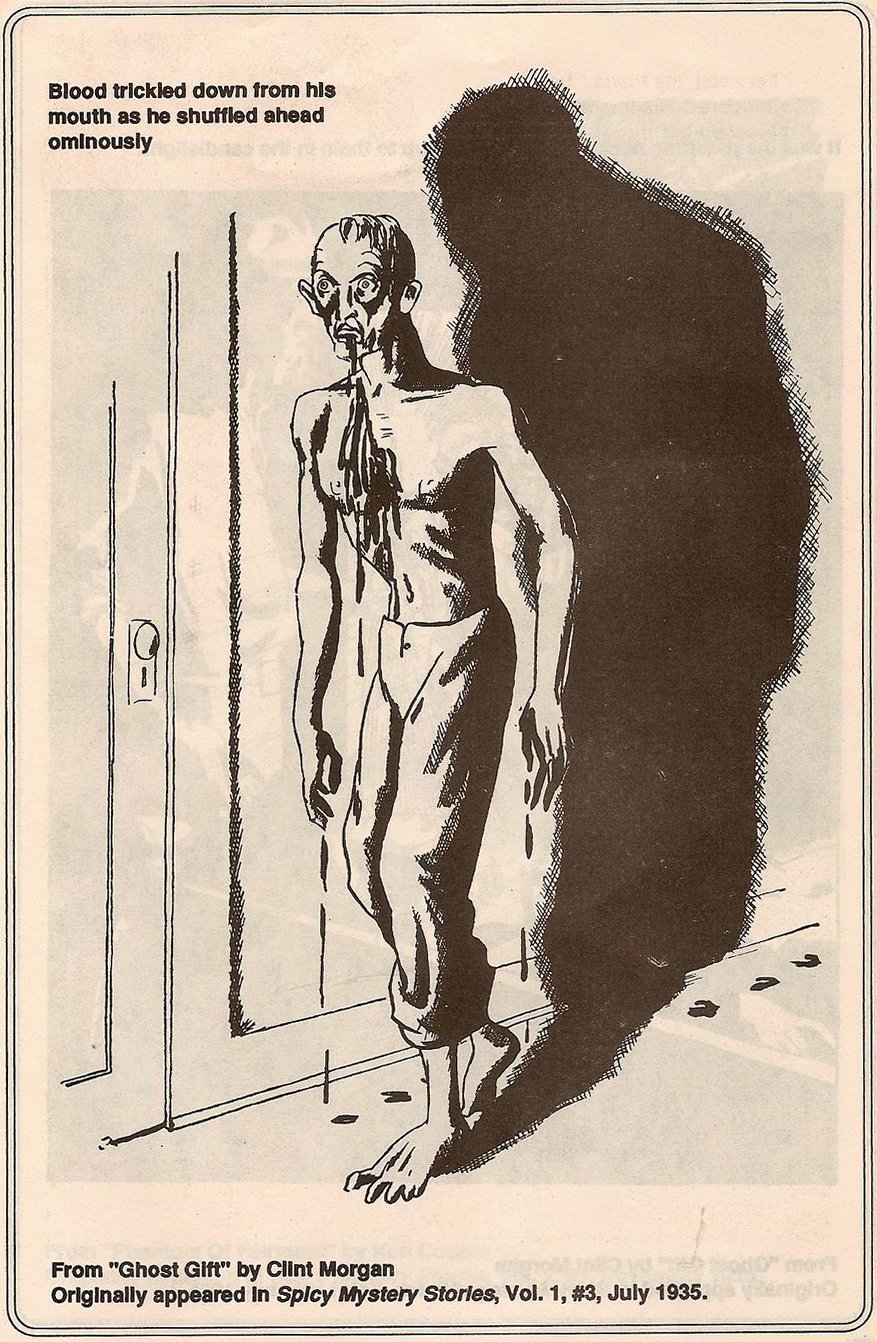

In any event, it was during the summer of 1934 that the Spicy explosion took place. Five companion titles were created, all cover-dated July. They were Spicy Adventure Stories, Spicy Mystery Stories, Snappy Adventure Stories, Snappy Detective Stories and snappy Mystery Stories. If the Snappies differed from the Spicies to any noticeable degree, it is not evident fifty years later. In any case, they did not enjoy the long life visited upon the Spicies.

It might be difficult for a modern reader used to explicit sex in fiction of all types to appreciate the innovative nature of the Spicy line. But until Culture Publications, pulp fiction was largely asexual. Some pulps, like Adventure, took this to extremes. No females of any consequence graced its masculine pages. Love interest may have appeared in certain kinds of stories, but it was chaste stuff. Sex stories certainly existed in a number of magazines which were not exactly pulps, being thinner and of larger dimensions. But these, like the aforementioned Pep and others, were devoted to the misadventures of opposite sexes during their respective meeting rituals. It was boy-meets-girl, boy-loses-girl, etc, with some mild titillation thrown in. Light-hearted stuff. Today, it could only be called “naughty”. In fact. Culture’s slant has been described as wilder than Breezy Stories yet mild- er than Pep.

Culture Publications took the harmless sex story and grafted it onto the red-blooded pulp genres of the day. Spicy Detective Stories featured hardboiled dicks — so to speak — involved in the seamier side of their profession. Spicy Adventure Stories took the sex story around the world to exotic locales where American — the heroes of the Spicies were always Americans — explorers and adventurers rescued half-nude white girls from various vicious ethnics and manfully, if seldom successfully, attempted to resist the charms of a luscious assortment of conniving foreign temptresses. Spicy Mystery Stories had a weird flavor. The tales revolved around ghostly or sinister manifestations, which were always explained rationally.

It was a genuine revolution which, while imitated, was never done with as much style and verve as Culture Publications managed to invest in their line.

The key to the Spicies was their clean, almost wholesome look— which was there even when the cover depicted a malignant dwarf shooting arrows at a scantily-clad girl tied to a giant bull’s-eye. The man most responsible for this look was cover artist H. J. Ward, who painted his girls in attractive, girl-next-door strokes and gave them enough clothes to preserve their decency without minimizing their charm — or “charms,” as the authors were wont to call their endowments. Accidentally or by design, the Spicy approach to female nudity had much the same appeal which made the early Playboy famous. Regardless of the pose or situation — and some were pretty wild — the Spicy Girl always looked wholesome, virginal, yet tantalizing.

Other artists, like H. Parkhurst, also painted Spicy covers, but Ward was the most used, best remembered, and his style was clearly the Spicy house style. Interior art was often the same, but more daring. Actual nudity was shown, but with details left obscured. Parkhurst did a number of interior pieces as well, as did Paul H. H. Stone and Max Plaisted. While most artists didn’t sign their work, one who did was Joseph Sokoli, whose sharp line drawings “spiced” most issues. (Later, he did abstract covers for the line, too.) Culture relied heavily on its artists, and even the shortest stories were heavily illustrated and set in large, very readable type.

The Spicy titles had a certain elegance that was almost, but not quite, at odds with its steamy subject matter. That may not have been evident in the Thirties, when the Legion of Decency was created (in the very same year the Spicies debuted!) to police movies, but today, when mainstream fiction is more explicit than the Culture editors ever dreamed of being, the content of most issues seems quaint, almost innocent.

Well, not quite. There was a certain amount of hot sex, sadism, illicit relationships, rape and questionable attitudes toward male/female coexistence. Yet when it came down to the raw facts, the Spicies blushed and turned away. Anatomical details eluded the authors. They enjoyed describing “swelling breasts” and “shapely thighs” and “creamy (or alabaster) skin,” but never described nipples or breathed a word about female pubic hair and its secrets. Men were not described in sexual terms at all. And when the foreplay was over, the paragraph would melt into ellipses . . . and the reader’s over-heated imagination was on its own.

The sexual angles, overplayed on the covers and interior art, were not as big a part of the stories as the packaging promised. True, sex was a preoccupation of most of the casts, but often nudity alone was the result. One Spicy contributor, Norman A. Daniels, claimed that whenever his other markets rejected a story, he just threw in some passing remarks about shapely feminine bodies and sent it to the appropriate Spicy title. Other writers report using this tactic, too.

The Spicy line, by 1936, included a new title, Spicy Western Stories. It was the last of the four main Spicy titles, yet it may have been one of the most logical ideas. Back in the Twenties, other publishers had successfully combined the love and western themes (the two best-selling pulp genres, by the way) with Ranch Romances and a host of very popular imitators.

But the Spicies were not all Culture-published. They inaugurated a related line under the Trojan Publishing Company name. The inspiration for the firm’s name is open to speculation. Its first title was Super Love Stories in 1934. The Trojan arm of Culture Publications was its more legitimate expression. Trojan eschewed salaciousness and published mainstream pulps. They were sold from the same racks that featured other pulps. Whether or not the Spicies were sold on newsstands or under-the-counter depends on who you talk to — but actually this may have varied according to where they were sold. It’s likely Trojan was incorporated as a separate entity to protect that line in case obscenity suits or censorship problems wiped out the Culture titles.

Trojan published a diverse group of magazines, including The Lone Ranger (based on the radio hero), Romantic Detective, and Private Detective Stories, where Robert Leslie Bellem’s Dan Turner found himself a new home, and prospered. In 1940, Frank Armer revived his old Super-Detective title, this time with a Doc Savage-type hero named Jim Anthony leading each issue and, oddly enough, during the first year, with a number of science fiction stories in the back pages. Later, it became a straight detective magazine, and Jim Anthony was dropped.

Bellem and his friend W. T. Ballard wrote the Anthony stories under the John Grange house name. While sex was not a staple of the Trojans, what was euphemistically termed “girl interest” was. Attractive young women were prominently displayed on most Trojan covers, often with a great deal of attention focused on nyloned legs and the “damsel in distress” motif. But this was just window dressing.

The exact relationship between the Culture and Trojan groups is deliberately unclear. In 1938, self-appointed censors began to go after the more conspicuous sex pulps. The heat reached the Culture line, which began to cool the “heat” in its pages. The old tepid descriptions of foreplay were dropped, but the covers remained as racy as before. Culture did this reluctantly, but caved in when the Post Office threatened to remove its second-class mailing privileges, without which subscription copies could not be mailed. A year later, in 1939, it was announced that Culture Publications had “changed owners” and severed its relations with what was called “Frank Armer’s New York group” — i.e., Trojan. But this may have been only a dodge, as later developments suggest. Coincidentally or not, D. M. Publishing (still publishing the old Spicy Stories) went out of business at this time.

in any case. Culture and Trojan continued publishing, sharing essentially the same stable of writers and artists, and a distinctly joint “house look.” But who were the Spicy writers?

Well, many of them, like Norman A. Daniels, were regular pulp hacks who submitted to the Spicies when the spirit moved them. Culture paid only ½ to 1 ¢ per word, but was a wide open market with a reputation for paying quickly. The bolder of these writers wrote for the Spicies under their own names. E. Hoffmann Price was one of these brave souls. (An interesting sidelight to Price’s Spicy work was two stories Clark Ashton Smith gave him after Smith found them unsalable. In 1940, Price rewrote them for Spicy Mystery. The first, “House of the Monoceros,” appeared in the February 1941 issue as “The Old Gods Eat,” while the second story’s fate is unknown. It was titled “Dawn of Discord.” Naturally, they were greatly changed in the telling.) John A. Saxon and Ken Cooper (who may or may not have also written as Edgar L. Cooper) were two of Culture’s regulars. Lars Anderson was almost the real name of Alan Ritner Anderson. Justin Case, one of the Spicy “house names,” was recently revealed to be Hugh B. Cave— all by himself!

Many of these writers specialized in sex stories for various publishers, and their bylines never appeared outside this field. One, a woman named Thelma B. Ellis, wrote for Culture under her own name, a female pen name and two male pen names — all now forgotten.

Others, like Laurence Donovan, started off in the Spicies, went on to write Doc Savage, the Phantom, the Whisperer and other pulp heroes, then ended up back in the Spicies. George A. MacDonald was another Phantom author who worked for Trojan. Mystery writer Wyatt Blassingame did Spicies as William B. Rainey. W. T. Ballard used the names Clive Trent and Isaac Walton — but whether these were his exclusive bylines or merely ubiquitous house names is unclear. Of course, Robert E. Howard did his share of these stories as Sam Walser. Roger Torrey — a real author — did a lot of work for Private Detective. Science fiction scribes like Henry Kuttner, Ray Cummings and Ralph Milne Farley (really ex-senator Roger Sherman Hoar) are known contributors — even if their bylines are not.

But the king of them all was the mild-mannered bespectacled Robert Leslie Bellem. Bellem did not fear to sign his own name to his stories — but he did so many that other bylines came into play to an amazing degree. His favorite Spicy bylines were Ellery Watson Calder, Harley L. Court, and Jerome Severs Perry; these were personal pen names. But he also wrote as Randolph Barr, Rex Daly, William Decatur, Walton Grey, John Grange, Paul Hanna, R. T. Maynard, Henry Phelps, Don Traver, Stan Warner, Hamilton Washburn, John Wayne (!) and Harcourt Weems. Exactly how many of these were house names may be beyond human rediscovery, but known ones include William Decatur, R. T. Maynard, and Max Neilson.

Bellem wrote in a glib, super-colloquial style, especially in his Dan Turner stories, where Turner, who narrated his own adventures, liked to describe female breasts by such code words as “pretty-pretties,” “tiddly-winks,” “bon-bons” and “whatchacallems.” It may be a measure of the Spicy audience’s mentality not only that Turner’s adventures ran for years in Spicy Detective and Private Detective, but that in 1943, Culture-Trojan began reprinting the older stories in Hollywood Detective, usually three to an issue. The publisher was given as Arrow Publications, a new arm nominally headquartered in Springfield, Massachusetts.

The reason for creating Arrow Publications was that the Culture line was disbanded (ostensibly, at any rate) in 1942. Official pressure had continued against the Spicies. New York’s mayor Fiorello La Guardia prevented the titles from being sold in Manhattan unless the covers were removed.

Culture realized that they’d run their course. They’d established hot titles in the big four pulp genres (only a Spicy Science Fiction Stories was overlooked — but then Spicy Adventure and Spicy Mystery did a lot of SF stories and covers in the early forties), diversified enough to cover their losses in any situation, and sales had slacked off. Frequently, older stories would be reprinted under new house bylines. So they finally killed off the Spicies.

But that wasn’t the end, by any means. At the beginning of 1943, Trojan started four new titles. Speed Adventure, Speed Detective, Speed Mystery and Speed Western Stories. Most were cover-dated January 1943. They weren’t as racy as the Spicies, but in their own way they were “fast.” Under the Arrow line, milder titles were established, including Leading Love and Western Love. Trojan came out with Leading Western, Blazing Western and Amour.

The Speed titles were edited by two men who had been with Trojan since the thirties, Wilton Matthews and Kenneth Hutchinson. They were responsible for the increasing use of reprints in the Spicy titles. Apparently, some of these Spicy stories were reprinted in the Speed titles, because in June of 1947 it was announced that Matthews and Hutchinson had been arrested and convicted of “check-juggling.” They were sentenced to two to four years apiece. It came out that they had engineered a racked as sweet as any published in the pages of Spicy Detective. They would “purchase” stories, publish them as new and pocket the checks, when actually they were passing off reprints culled from the back pages of their own titles. Because the Spicies bought all rights, and because this canny duo always changed the bylines when they reprinted, the original authors had nothing to complain about even if they realized their stories had appeared again. (This is why some Robert E. Howard Spicy Adventure stories were reprinted under various house names.) Apparently one of these two masterminds pretended he wrote these “new” stories. In any event, they were caught and put away. As a result, the Arrow, Trojan and Speed lines were consolidated.

It would be poetic if the whole Culture/Trojan story had ended on such a deliciously sordid note, but it didn’t. Many titles continued, and in 1948, a year after the “consolidation,” Frank Armer officially stated he had only four active titles left — Hollywood Detective, Private Detective, Fighting Western and Leading Western. The new editor was listed as Adolphe Barreaux. Supposedly the Donenfeld family divested themselves of their Spicy interests in the wake of their great comic book success.

Yet despite these claims, other titles continued. It seems that some of the Speed titles and Super-Detective continued until at least 1949 or 1950. Perhaps another outfit bought them out. Certainly by no later than 1951, if then, the whole operation had folded, its offices (wherever they were by then) closed, and its authors scattered to other pursuits (Bellem went to Hollywood to script The Lone Ranger and Superman). Even Dan Turner retired. The Spicies had seen their day in the sun — or was it their evening under the moon?

Although Culture Publications had taken a great deal of heat over the years, by 1950 standards they were already passe even in their most extreme form. The new and burgeoning paperback industry pushed the limits of propriety leagues beyond anything Armer envisioned; they dealt directly with themes like interracial love, homosexuality and other once-taboos, leaving the entire Culture/Trojan approach to sex stories in the dust and rendering the very term “spicy” antique.

The fact is that the Spicies were extremely tame. Where some of the more lurid imitators plunged head- first into sexual sadism combined with horror, Culture soft-pedalled such approaches. Competing titles like Horror Stories and Uncanny Tales regularly cover-featured scenes of indescribable (and sometimes inadvertently hilarious) torture with titles like “Daughters of Lusting Torment,” “The Monster Wants More Than a Mate” and “The Claw Will Come to Caress Me.” Culture covers were restrained by comparison, and their titles seldom had sexual connotations. Most of them, like “She from Beyond, ” “Ghosts in Her Eyes” and “Dance of Damballa,” could have appeared in almost any pulp magazine. This is not to whitewash the Spicies; their slant was unabashedly erotic, their purpose to titillate. It’s just that they were so immature about it. When Armer started operations back in 1934, he instructed his writers that “Our stories border on the risque, the situations may be compromising and passionate but there must be no ac-tual ‘consummation of love.'” Even the way he describes it today seems quaint and vaguely prudish.

In retrospect, one of the features carried by every Spicy seems to speak eloquently of the playful element that characterized them. Each title ran its own serialized comic strip. It started with “Sally the Sleuth,” a four-page feature in which the blonde detective invariably found herself in distress and undress. This, appeared in Spicy Detective and was: signed, if memory serves, “Adolpha Barreaux.” Spicy Adventure featured a female Flash Gordon named Diana Daw, ostensibly by Clayton Maxwell. Spicy Mystery tried “The Adventure of Olga Mesmer,” the Girl with the X-Ray Eyes (creator Watt Dell explained that her strange powers, “dormant” during her childhood, “burst into light once she is aroused, and Olga embarks upon a remarkable career”) but replaced her with another distaff spacegirl, Vera Ra, by the same writer. The sexual content of these strips was limited to the heroines stripping to their underwear when the going got rough. One gets the impression these strips were there for the edification of the pre-pubescent. And speaking of pre-pubescent types, adventurer Dan Turner got his own comic strip in Hollywood Detective. Naturally, Bellem did the writing.

The Spicies are long dead now. No vestige of the former pulp empire exists, and there are no records to reveal the secrets behind such frequent but mysterious Spicy bylines as Lew Merrill, Robert A. Garron, Morgan La Fay, C. A. M. Donne and Cliff Ferris. Only the magazines remain, and not many of these. What does survive of those once-mighty print runs belongs in the domain of the serious pulp collector who may collect them for nostalgia, for the lush H. J. Ward covers or even for their faintly risque charm — but certainly not for their titillation value. The world outgrew the big, bad Spicies a long, long time ago.