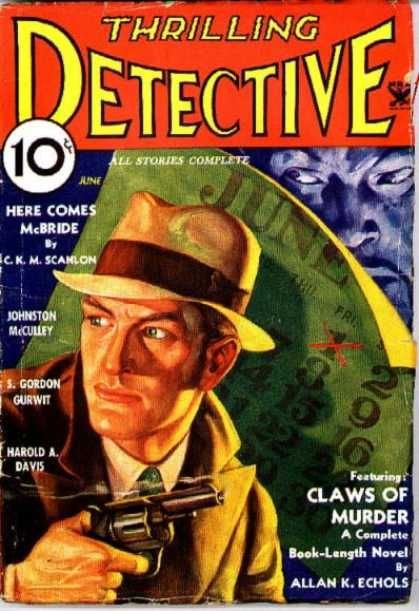

Bacchus researches a colorful anecdote in the history of the decline of the shudder pulps, one referenced in in this post from last Thursday.

There are so many accounts of New York City mayor La Guardia’s infamous explosion upon seeing a particular Spicy Mystery cover in 1942 — and so much impact on the shudder pulp industry attributed, probably falsely, to the incident — that it seems sensible to accumulate all of the anecdotes in one place for comparison and contrast of details. It’s worth pointing out that the the shudder pulps in general were well into their terminal decline at this point (see timeline) and that any fallout or follow-through from this incident would not have been La Guardia’s first attempt at censoring pulp magazines in NYC; those began at least as early as 1934 (see the Smut Suppression article from Time, forthcoming on this site.)

From The Village Voice in 2003:

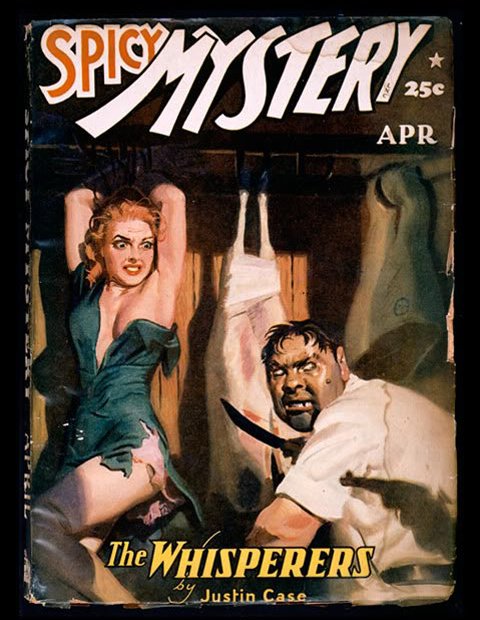

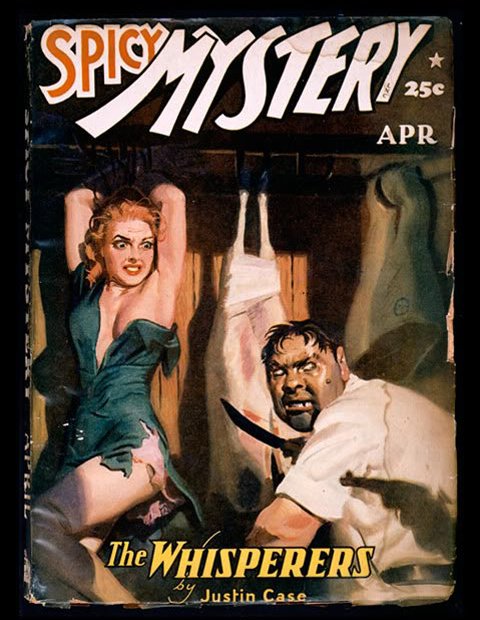

In 1942, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia spied a Spicy Mystery magazine on a New York City newsstand. H.G. Ward [sic; reference should be to H. J. Ward] (a pulp cover artist who never missed the chance to lovingly delineate a mons veneris under clingy fabrics) had portrayed a woman strung up in a meat locker and threatened by a hunchbacked butcher. Apparently missing the compositional nod to Caravaggio’s Abraham and Isaac, Hizzoner forced the publisher out of the pulp business.

(Spicy Mystery underwent a name change and a shuffle in corporate ownership, but in truth La Guardia’s famous fit of pique did not, at least by itself, force anybody out of business.)

Blogger Terrance Towles Canote wrote in a 2014 piece on the decline of shudder pulps:

The cover of the April 1942 issue of Spicy Mystery came to the attention of New York City mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia. The cover featured a woman, her clothes in tatters, dangling from a meat hook in a freezer, while being menaced by a hoodlum with a large and sharp looking knife. Mayor La Guardia,who had cracked down on the spicy pulps and other “dirty magazines” in the Thirties, then cracked down on pulp magazines. Even more mainstream pulp magazines such as Weird Tales, would be affected by the mayor’s crackdown on the pulps; its covers by Margaret Brundage would be considerably tamer afterwards. As to the shudder pulps and the much racier spicy pulps, they more or less ceased to be.

Almost everything that follows the anecdote here is wrong, or at least hopelessly confused as to timeline. According to Wikipedia and other sources, Margaret Brundage stopped drawing sexy covers for Weird Tales in 1938, possibly in part because of La Guardia’s earlier pressure on pulp publishers. And the shudder pulps were pretty much finished already by 1942 when La Guardia blew his top. Finally, there’s very little documentation (as the rest of these collected anecdotes will show) of what, if anything, La Guardia did in a concrete way to burden pulp distribution in NYC after exploding in an indignant show for the reporters.

The Smithsonian Magazine goes so far as to put actual words in La Guardia’s mouth:

When New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia passed a newsstand in April 1942 and spotted a Spicy Mystery cover that featured a woman in a torn dress tied up in a meat locker and menaced by a butcher, he was incensed. La Guardia, who was a fan of comic strips, declared: “No more damn Spicy pulps in this city.” Thereafter, Spicies could be sold in New York only with their covers torn off. Even then, they were kept behind the counter.

Some version of the claims in those two final sentences is often repeated, but documenting them from original sources has proved elusive. Although the Spicies did not long exist after that (see main article and timeline) cause and effect are harder to put in proper order.

This next account tends to support La Guardia’s quoted words in the Smithsonian story, fairly closely anyway:

One day in April 1942 Mayor la Guardia spied an unusual Spicy mystery on the newsstand and exploded in instant rage. He ruled on the spot: “No more Spicy pulps in this city.”

That’s said to be from the book Pulp Art by Robert Lesser (Gramercy Books 1997).

Another account of La Guardia’s reaction comes from Damon C. Sasser, who tells it thusly:

When New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia spotted the April 1942 issue of Spicy Mystery Stories magazine on a newsstand that sported a cover depicting a woman strung up in a meat locker being menaced by a homicidal butcher, he declared war on the Spicy line. The Mayor decreed that any magazine with a lurid cover had to be sold with the cover removed. Sadly, Margaret Brundage’s Weird Tales covers were among those singled out for destruction.

Again, no contemporary documentation of any such “decree” has been located.

The New York Times tells the same story, with a lot more color but omitting any mention of action on La Guardia’s part except for the angry noise all seem to agree that he made on the spot for reporters:

Mayor La Guardia was appalled. Out for a walk one day in Manhattan in 1942, he happened upon a store displaying a copy of a periodical called Spicy Mystery. In lurid hues and slashing graphic style, its cover pictured a curvaceous, terrified young woman in a partly shredded dress hanging by bound hands from a hook alongside slabs of meat. She was menaced by a demented, knife-wielding brute of a man who looked back over his shoulder at whoever was holding the gun that cast its shadow on him. Shocked and dismayed, the mayor vowed to ban all such scurrilous literature from his fair city.

All agree: this was a colorful moment of mayoral choler. The impact, if any, it had on the ongoing decline of the shudder pulps is rather more debatable, but the murky truth is a lot harder to nail down than this colorful anecdote is to tell.