Cleo’s adventures abroad invoke a different line of wishful thinking about possible abroads free from morality.

Cleo’s adventures abroad invoke a different line of wishful thinking about possible abroads free from morality.

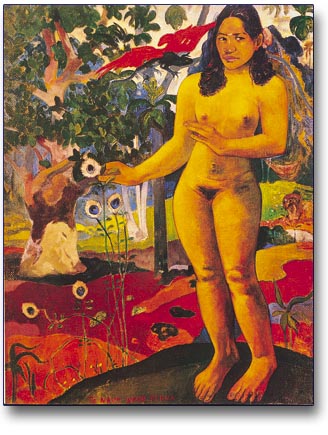

As far back at least as Denis Diderot‘s Supplément au voyage de Bougainville (1772) the dream of a tropical paradise free from labor, free from politics, and largely free from clothes has loomed large in the imagination of Greater Europe. It is probably not hard to see why, above and beyond the fact that the tropics are fecund and also a place in which you can comfortably run around naked (indeed, might often be more comfortable if you are). They also had the advantage of being very remote, and therefore a convenient literary topos for writing a critique of your own miserable, prudish, Christian society — the more remote the place, the harder it would be for your beautiful theory to be slain by unpleasant facts.

Small wonder that Tahiti ended up being the place Paul Gauguin chose to flee to, and whence he provided us with some of the most beguiling art in service of the myth, even if the myth turns out not to really have had much going for it.

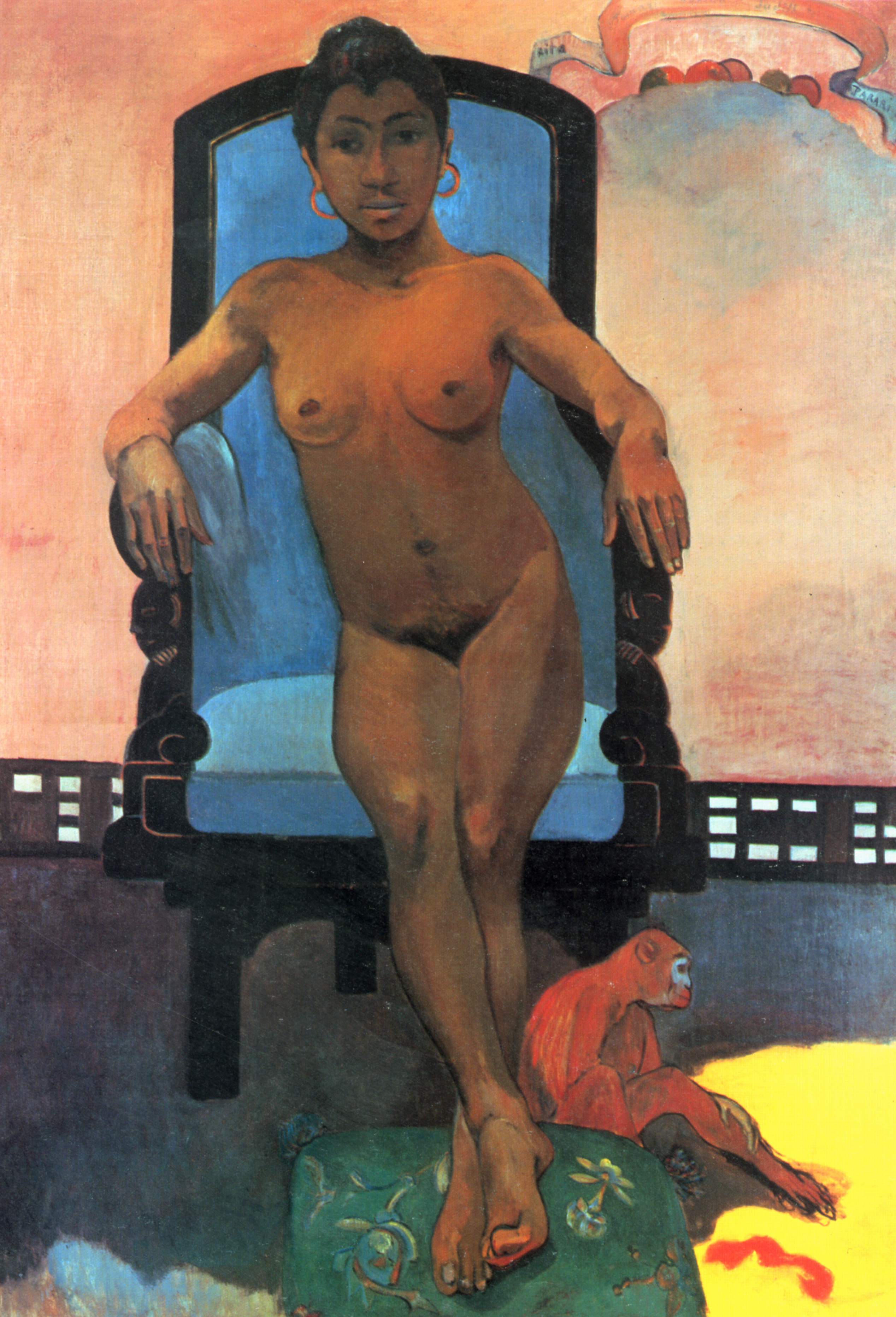

Paul Gauguin (1848 - 1903), "Annah, die Javanerin" (1893)

Of course in time this tradition of “tropical paradise” would be given a sick twist in cinema in the form of the Italian jungle cannibalism film: a subject which I’ve written on briefly before. Here the morality-free zone once imagined as a Rousseauian paradise is replaced with one imagined as a Sadean hell. Witness for example Janet Agren here in deep erotic peril in Mangiati vivi (1980).

No cannibalism for lucky Cleo, though. The people she meets are altogether more benign.

Being eaten has to wait for another character entirely…