Bacchus’s research continues

There can be little doubt that from the earliest days of the shudder pulp / weird menace publishing boom, the publishers of these magazines were raking in their dough with one eye firmly on the door of the counting rooms, watching for the censorious police to break it down and end the party. This paragraph in Will Murray’s Informal History of The Spicy Pulps is particularly telling:

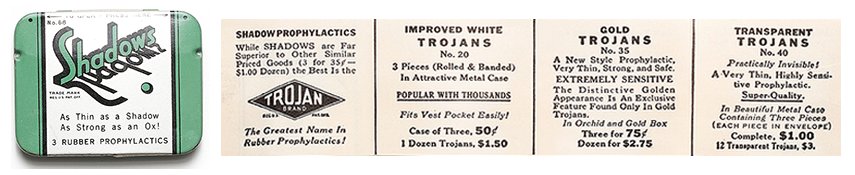

But the Spicies were not all Culture-published. They inaugurated a related line under the Trojan Publishing Company name. The inspiration for the firm’s name is open to speculation. Its first title was Super Love Stories in 1934. The Trojan arm of Culture Publications was its more legitimate expression. Trojan eschewed salaciousness and published mainstream pulps. They were sold from the same racks that featured other pulps. Whether or not the Spicies were sold on newsstands or under-the-counter depends on who you talk to — but actually this may have varied according to where they were sold. It’s likely Trojan was incorporated as a separate entity to protect that line in case obscenity suits or censorship problems wiped out the Culture titles.

Note the dates! Trojan Publishing Company’s supposed prophylactic business purpose (and yes, that double-entendre was available to the men who owned Trojan Publishing Company) is consistent with its establishment in the same year as Modern/Culture Publications, and Trojan was operated conservatively throughout the Spicy’s spectacular run, and beyond. When the Spicy titles got renamed “Speed”, the listed publisher was Trojan, and the new titles were reduced in salaciousness to match the more-conservative Trojan house positioning.

Here’s Murray again:

Official pressure had continued against the Spicies. New York’s mayor Fiorello La Guardia prevented the titles from being sold in Manhattan unless the covers were removed. Culture realized that they’d run their course. They’d established hot titles in the big four pulp genres (only a Spicy Science Fiction Stories was overlooked — but then Spicy Adventure and Spicy Mystery did a lot of SF stories and covers in the early forties), diversified enough to cover their losses in any situation, and sales had slacked off. Frequently, older stories would be reprinted under new house bylines. So they finally killed off the Spicies. But that wasn’t the end, by any means. At the beginning of 1943, Trojan started four new titles. Speed Adventure, Speed Detective, Speed Mystery and Speed Western Stories. Most were cover-dated January 1943. They weren’t as racy as the Spicies, but in their own way they were “fast.”

What’s fascinating here — if perhaps not directly germane to shudder pulp history — is that that the Amer/Donenfeld partnership at Culture/Trojan got its start in the early 1930s with a similar censorship-ducking dodge, as Amer defused an earlier wave of censorship aimed at his long-running girlie pulps of the 1920s:

In May 1932, Armer surrendered the gems of his line, Pep Stories and Spicy Stories, to Harry Donenfeld for printing debts owed; in like manner, Donenfeld accrued many girlie pulp titles during the 1930s… Bowing out gracefully, Armer did Donenfeld an additional service by making a ploy to deflect the censors part of the deal.

In spring 1932, the New York Committee on Civic Decency had pressured the police to arrest four newsstand owners for selling girlie pulps. At a July meeting with the Committee, charges against the four owners were dropped after Armer and other editors promised to “tone-down” their content and “pay closer heed to the proprieties” — as well as cease publication of Ginger Stories, Hollywood Nights, Gay Broadway, Broadway Nights, French Follies, and La Paree. Donenfeld continued to print La Paree in spite of this agreement, and in addition to Ginger and Broadway Nights, Armer probably had a controlling interest in Henry Marcus’ (Pictorial) French Follies and Hollywood Nights. So Armer’s pulps, which were going out of business in any case, became the sacrificial lambs, while newsstand owners were off the hook — at least for the time being.

We have established that the men who were gearing up to publish salacious pulps — including shudder pulps — in the 1930s were alert to the risks of formal censorship, and experienced in handling those risks. But what censorship activity did they actually face, and what were its effects on the shudder pulp business?

One name that comes up over and over again is that of New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. A notorious prude and blue-nose remembered at least as vividly for putting burlesque theaters out of business, La Guardia seems to have ruled mostly by bare-knuckled administrative fiat, leaving not much paper trail behind his billy-club-toting cops. Most of what survives about his pulp censorship efforts is colorful summary and commentary. I’ve compiled that in a couple of stand-alone articles, which can be boiled down here as follows:

- In 1934, as reported in Time magazine, LaGuardia issued some sort of order to the police directing that 59 salacious magazines be no longer exhibited or sold at New York City newsstands. Titles included Spicy Stories, publishers listed included Culture Publications, and Harry Donenfeld gives a juicily obnoxious quote. There is promise of litigation from multiple parties, including the “Civil Liberties Union.”

- Numerous sources refer to “a new decency standard after 1938” or “censorship in 1938” with Mayor La Guardia fingered as the cause, as will be detailed in a future post. Perhaps it is also no coincidence that NODL was founded about this time.

- Finally, there is Mayor La Guardia’s infamous staged explosion for reporters in 1942, when he lost his mayoral shit upon seeing a copy of the April 1942 Spicy Mystery Stories. These stories are so many and varied that they to will be detailed in a future post. However, whatever effect Mayor Laguardia’s stunt did or did not have on the publishing environment for Spicies in New York City in 1942 and subsequently, most shudder pulps had already ceased publication before that fateful (or not) day.

To be continued.