I’ve often wondered what might have lead to my writing something like this exchange in The Apsinthion Protocol.

MOIRA

It would be a one-way trip for whoever did it.

NANETTA

It would mean giving up everything in this world.

MOIRA

And possibly entering a far more wonderful one.

NANETTA

Or it might mean a few moments of ecstasy, and then annihilation.

MOIRA

And there is likely very little time to decide.

(In my bleak moments I often think that what Nanetta and Moira would eventually achieve — even if it was just blissful annihilation — would be superior to the alternative: adulthood.)

One finds one’s erotic inspiration where one is. Where I was for a lengthy stretch of young adulthood was Harvard’s Widener Library. Had I had my druthers, the erotic inspiration would have taken the form of a studious-but-sultry meganekko but sadly there was a severe druthers shortage in Cambridge at the time and so I didn’t get mine.

There was, however, this mural executed by John Singer Sargent (1856-1925).

A doughboy embraces death and victory in the same moment. (We know he’s victorious because there’s a defeated figure in a stahlhelm at his feet, presumably one of those nasty wicked Germans.) At the time I would pass this mural daily (it’s on the library’s main entrance stairs) my conscious thoughts were that it was a singularly shameless bit of militaristic propaganda.

My subconscious thoughts, I conjecture, were on a different track entirely, thinking that maybe it’s cool — erotic even — to throw one’s life in like that. It’s a natural interpretation — look at the soldier’s face, it’s expression and positioning under Victory’s bared breast. It would explain a lot about the sort of things I’ve written.

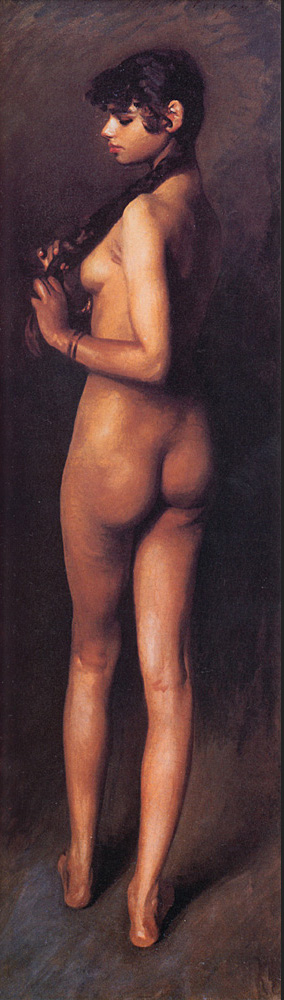

Sargent didn’t do much in the more explicitly erotic line, although there is some, for example this study of a nude Egyptian girl.

Orientalist art — something I’ve found appealing before.

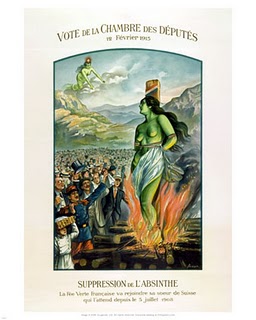

The Green Fairy was banned for a long time, even in the countries was distilled. The wormwood used to make her allegedly contained a dangerous narcotic, but more likely the ban (at least in France) was a form of industrial protectionism for French winemakers. (That’s the way it so often is, isn’t it? “For our own good” is a way of lining others’ pockets.) The ban itself at least was an occasion for some interesting art lampooning authoritarian politics, as in the example to the right, commemorating the ban in Switzerland, which followed that in France. Here the Green Fairy is burned at the stake (her French sister awaits her in heaven).

The Green Fairy was banned for a long time, even in the countries was distilled. The wormwood used to make her allegedly contained a dangerous narcotic, but more likely the ban (at least in France) was a form of industrial protectionism for French winemakers. (That’s the way it so often is, isn’t it? “For our own good” is a way of lining others’ pockets.) The ban itself at least was an occasion for some interesting art lampooning authoritarian politics, as in the example to the right, commemorating the ban in Switzerland, which followed that in France. Here the Green Fairy is burned at the stake (her French sister awaits her in heaven).