As an ardent thaumatophile, I cannot but love the idea of a person scanner, and so does Iris, apparently.

The idea of a scanner that can take your information for re-creation of you later on somewhere else out of new matter is one that has played an important role in thinking about the metaphysics of personal identity. The beginning of Chapter 10 (“What We Believe Ourselves to Be”) of Derek Parfit‘s Reasons and Persons contains a famous example.

I enter the Teletransporter. I have been to Mars before, but only by the old method, a space-ship journey taking several weeks. The machine will send me at the speed of light. I merely have to press the green button. Like others, I am nervous. Will it work? I remind myself what I have been told to expect. When I press the button, I shall lose consciousness, and then wake up at what seems like a moment later. In fact I shall have been unconscious for about an hour. The Scanner here on earth will destroy my brain and body, while recording the exact states of all my cells. It will the transmit this information by radio. Traveling at the speed of light, the message will take three minutes to reach the Replicator on Mars. This will create, out of new matter, a brain and body exactly like mine. It will be in this new body that I shall wake up.

Happily this process works, and Parfit’s narrator goes through it many times, until one day…

Several years pass, and I am often Teletransported. I am now back in the cubicle, ready for another trip to Mars. But this time, when I press the green button, I do not lose consciousness. There is a whirring sound, then silence. I leave the cubicle, and say to the attendant, “It’ not working, what did I do wrong?”

“It’s working,” he replies, handing me a printed card. This reads, “The New Scanner records your blueprint without destroying your brain and body. We hope that you will welcome the opportunities this new technical advance offers.”

The attendant tells me that I am one of the first people to use the New Scanner. He adds that, if I stay for an hour, I can use the Intercom to talk to and see myself on Mars.

“Wait a minute,” I reply. “If’ I’m here I can’t also be on Mars.”

Someone politely coughs, a white-coated man who asks to speak to me in private. We go to his office, where he tells me to sit down, and pauses. Then he says “I’m afraid we’re having problems with the New Scanner. It records your blueprint just as accurately, as you will see when you talk to yourself on Mars. But it seems to be damaging the cardiac systems when it scans. Judging from the results so far, though you will be quite healthy on Mars, here on earth you must expect cardiac failure within the next few days.”

The attendant later calls me to the Intercom. On the screen I see myself just as I do in the mirror every morning. But there are two differences. On the screen I am not left-right reversed. And, while I stand here speechless, I can see and hear myself, in the studio on Mars, starting to speak.

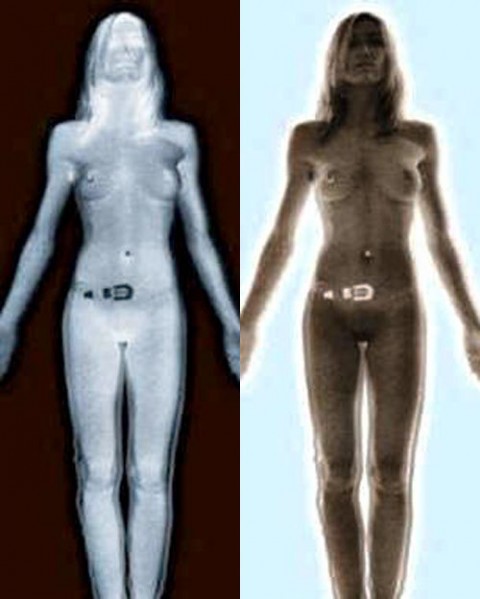

Get all that? Ponder it in your head for a moment while you savor another EroticMadScience picture of a scanner at work (though this one is real, not fictional, as you’ll see if you click through on the link).

The point of Parfit’s example is to sharpen (and challenge) our intuitions about what it means to be ourselves and survive as ourselves. There are many different possibilities, the most salient of which are physical continuity and psychological continuity. Since normally your consciousness and your body don’t separate, we don’t experience challenges of this kind in reality.

But Iris is smart. She knows that the two might be separated. Being forced to decide between the two possible theories is at the core of her disagreement with Professor Gregg in the prologue to Study Abroad. Gregg subscribes to a physical continuity theory of personhood, which is why he thinks that the permanently-vegetative “Tabitha Sibling” (fictitious, but arguably based on a real case) has the same moral status as “you or me.” Iris advances contrary to this the psychological continuity theory of personhood.

There is a problem, of course, which is that if we take a hard line on psychological continuity we might end up with a rather big bullet to swallow, to wit, that if we are in the position of Parfit’s narrator, we shouldn’t at all regret the fact that we are about to die of heart failure in a few days, because the guy on Mars is us, psychologically continuous with us, will have conscious experiences like ours, will carry on our projects, love our spouse, rear our children and so on just like we would have done.

Head spinning yet? Oh, but I’m not letting you off quite that easily. The same issues are entertainingly discussed further in a brilliant short film by John Weldon, called “To Be.” Watch at any time: unusually for something here at Erotic Mad Science, it’s completely SFW. As to whether it’s safe for your peace of mind, I make no warranties.

The awesome thing about Iris is that, unlike most philosophers, she is willing to put everything on the line, her very existence as a test of the theory she espouses. She (with a little boost with tolmemazine, perhaps? — that in itself poses an interesting philosophical problem) shows herself to be an absolutely fearless bullet-biter. This is experimental philosophy à l’outrance.

Just speculating here, but I’d bet that if in the real-world philosophers were half that courageous, philosophy would command much more respect.

ADDED 11 p.m. The woman in the scanner shot is apparently a hoax that appeared on both Gizmodo and Drudge Report so my “real” claim turns out to be wrong. But I at lesat hope the entertainment value remains, and, I think, the larger philosophical point raised by the post is unimpaired.