This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please keep in mind that any moral rights the artist has remain intact under this license.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please keep in mind that any moral rights the artist has remain intact under this license.

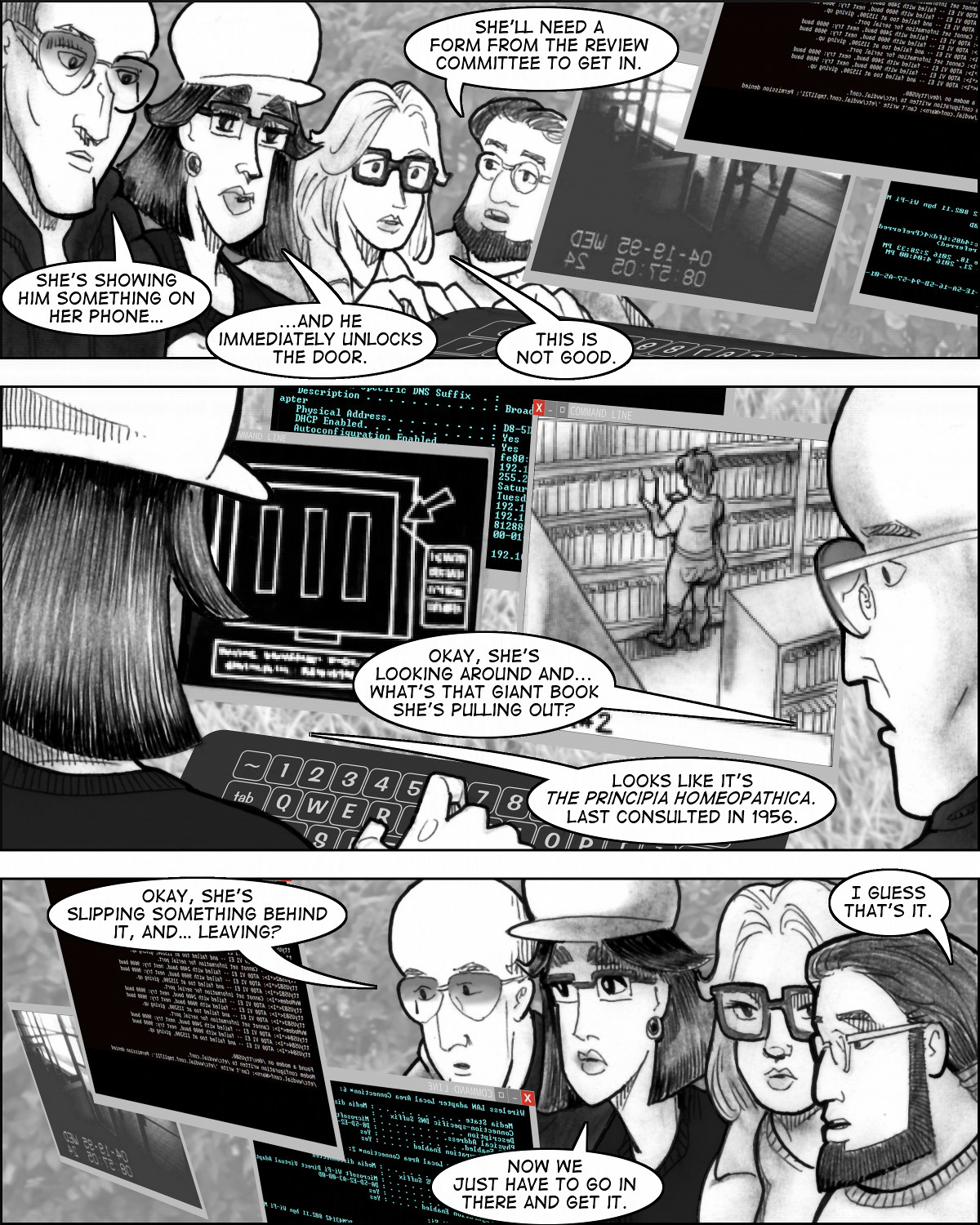

Bacchus’s research continues.

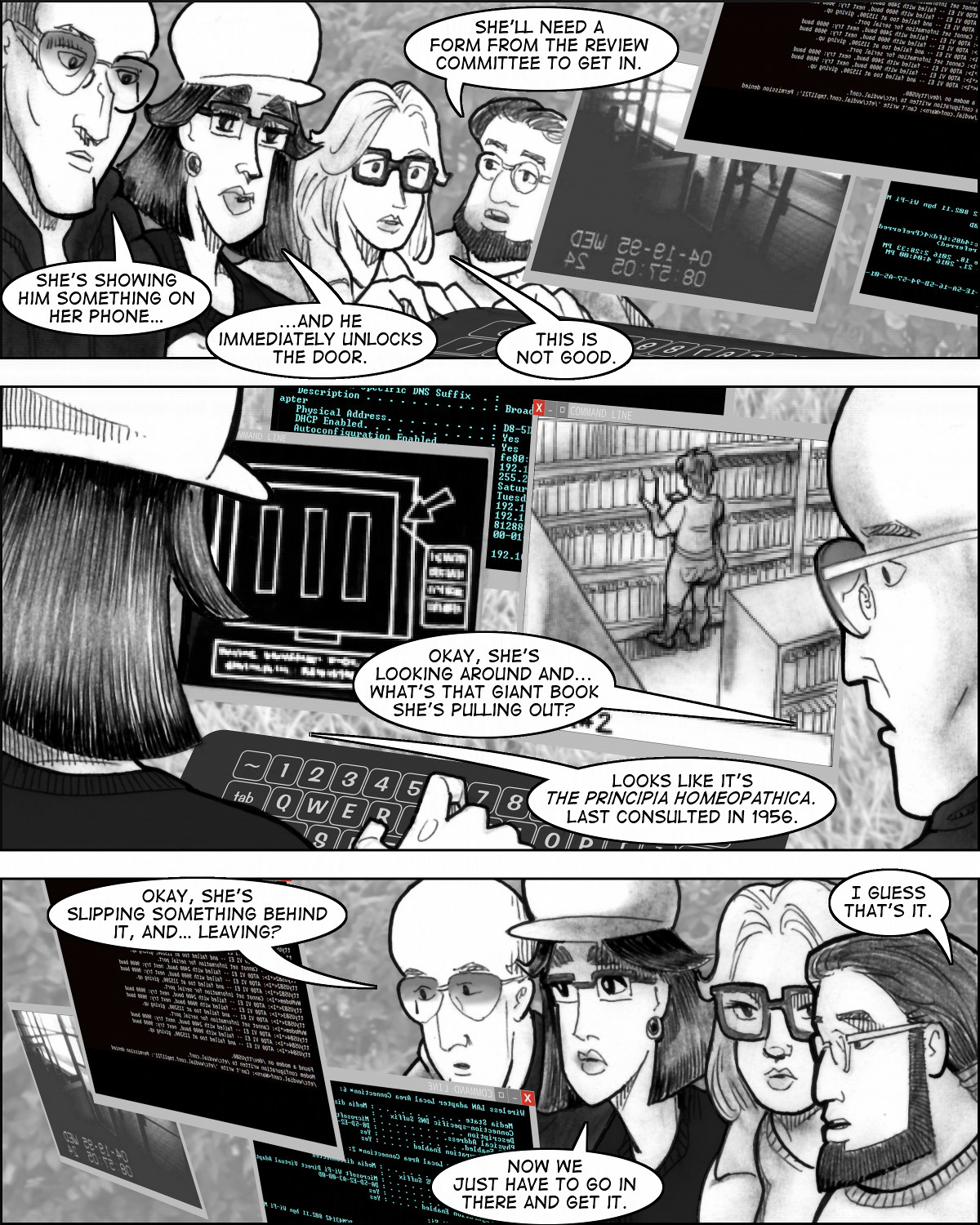

In his Pulp Horrors Of The Dirty Thirties essay previously cited, Don Hutchison took the view that World War II and its horrors affected the national mood in a way that began to drive nails into the shudder-pulp coffin:

“With the coming of World War II, the extent of human madness and misery could no longer be viewed — much less enjoyed — as mere fiction. In a more innocent time, it was thought that the brand of horror perpetrated by the fiends of the shudder pulps was purely imaginary. Now people knew that such things — and worse — were possible.”

Of course there are timing issues to be considered; the worst horrors of WWII came to light long after shudder pulps were history. Still, blogger Terrence Hanley is in accord, explaining the demise of a particular title:

[The shudder pulp titles] Terror Tales and Horror Stories came to an end a year later, in spring 1941. By then, torture, blood, and violence were no longer mere abstractions, for World War II had begun. Fiends and madmen ruled not just the pages of pulp magazines but also half the planet.”

War-related resource constraints are often cited without much evidence in broad-ranging opinion pieces about the demise of pulps more generally. It is true that paper rationing, labor shortages, and possibly constraints on availability of printing equipment and supplies all constrained various parts of the print entertainment industries in the early 1940s. But as the timeline makes clear, the shudder pulps in particular were closing doors left and right by 1941. Thus, this research did not seriously consider war-related resource constraints on the shudder pulp trade. See, e.g., Blake Bell’s observation (above) that “pulps were dying” in early 1941 at a time when WWII was “about” to put a crunch on paper supplies and thus had not yet done so. The Secret History of Marvel Comics: Jack Kirby and the Moonlighting Artists at Martin Goodman’s Empire (Blake Bell, 2013)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please keep in mind that any moral rights the artist has remain intact under this license.

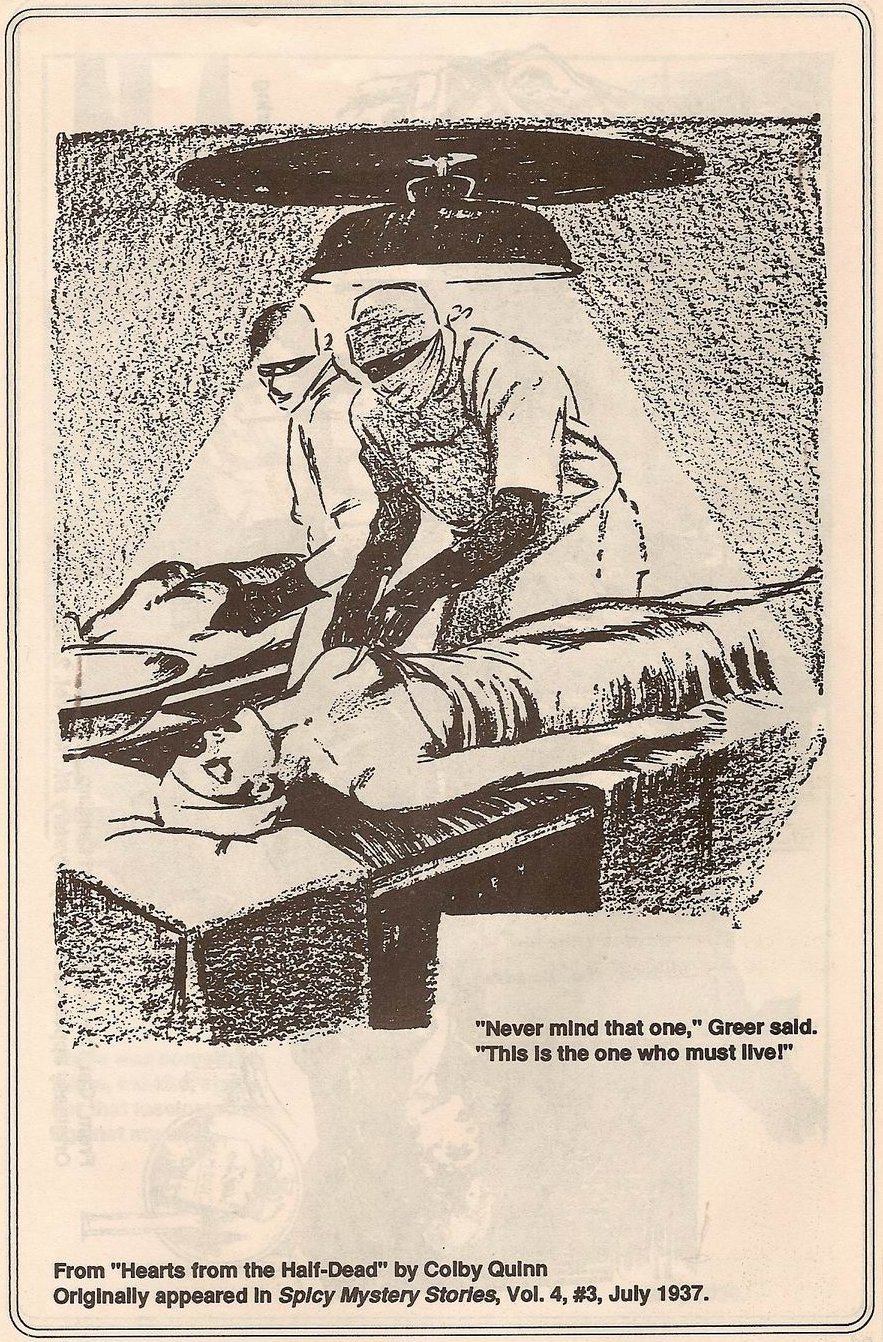

Bacchus’s research continues

There’s a discussion here (informed by, and perhaps quoting, although the extent of quotation is unclear, Ron Goulart’s Dime Detectives book) arguing that pulps were completely supplanted by paperback books and television (the discussion apparently omits/forgets comic books). Although television is largely a post-WWII phenomenon, the paperback book boom began in 1939, which is, timing-wise, appropriate to be a nail in the shudder pulp phenomenon. It’s appropriate here to point out that, as Will Murray pointed out in his Informal History Of The Spicy Pulps, the shudder pulps could not even begin to compete with the paperback book industry for salaciousness:

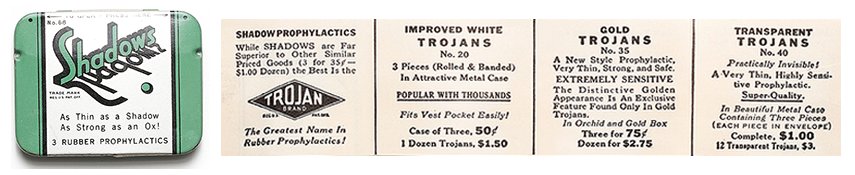

“The new and burgeoning paperback industry pushed the limits of propriety leagues beyond anything Armer envisioned; they dealt directly with themes like interracial love, homosexuality and other once-taboos, leaving the entire Culture/Trojan approach to sex stories in the dust and rendering the very term “spicy” antique.”

Blake Bell, writing in his 2013 book The Secret History of Marvel Comics: Jack Kirby and the Moonlighting Artists at Martin Goodman’s Empire about the one-issue run of Martin Goodman’s 1941 Uncanny Stories, said the short run

“was symptomatic of what was happening in the pulp industry. Pulps were dying, even banned in Canada, comic books were on the rise, and World War II was about to put a crunch on paper supplies.”

(Note: the reference to a pulp ban in Canada apparently refers not to any sort of censorship relevant to this research, but to >a purely protectionist trade ban on imports of US pulps, a subject which will merit a future post of its own.)

As pulps declined in general, the way magazines were published and distributed was changing too. Jane Frank, writing on the website of LonCon 3, the 72nd World Science Fiction Convention, says that pulp sales generally were in decline by 1938 and that distribution was lacking: “In 1938 the magazine industry was in the process of transforming itself, from one based on many independently published pulp magazines to one based on magazine chain ownership. The pressures of decreasing sales and lack of distribution caused many pulp publishers to sell to larger magazine chains.”

Years later, more distribution changes appear to have put the final nails in the coffin of the pulp industry generally. Writing about the economic impact of the Comics Code in 1954, Lawrence Watt-Evans says:

The comics market was declining at the time anyway, and at very nearly the same time that the Code came in there was a major shake-up in the magazine distribution system — the American News Company, by far the largest distributor in North America, was liquidated by its stockholders. The result was that the other distributors didn’t have the capacity to handle all the magazines being published, and were able to pick and choose which they would handle.

Naturally, they picked the more profitable ones.

That was what finally killed off the pulps; they’d been fading for years, and the distribution realignment finished them off. Fiction House folded completely; several other pulp publishers managed to get into publishing “slicks,” as the glossy, higher-priced magazines were called.

To be continued.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please keep in mind that any moral rights the artist has remain intact under this license.

Bacchus’s research continues

There can be little doubt that from the earliest days of the shudder pulp / weird menace publishing boom, the publishers of these magazines were raking in their dough with one eye firmly on the door of the counting rooms, watching for the censorious police to break it down and end the party. This paragraph in Will Murray’s Informal History of The Spicy Pulps is particularly telling:

But the Spicies were not all Culture-published. They inaugurated a related line under the Trojan Publishing Company name. The inspiration for the firm’s name is open to speculation. Its first title was Super Love Stories in 1934. The Trojan arm of Culture Publications was its more legitimate expression. Trojan eschewed salaciousness and published mainstream pulps. They were sold from the same racks that featured other pulps. Whether or not the Spicies were sold on newsstands or under-the-counter depends on who you talk to — but actually this may have varied according to where they were sold. It’s likely Trojan was incorporated as a separate entity to protect that line in case obscenity suits or censorship problems wiped out the Culture titles.

Note the dates! Trojan Publishing Company’s supposed prophylactic business purpose (and yes, that double-entendre was available to the men who owned Trojan Publishing Company) is consistent with its establishment in the same year as Modern/Culture Publications, and Trojan was operated conservatively throughout the Spicy’s spectacular run, and beyond. When the Spicy titles got renamed “Speed”, the listed publisher was Trojan, and the new titles were reduced in salaciousness to match the more-conservative Trojan house positioning.

Here’s Murray again:

Official pressure had continued against the Spicies. New York’s mayor Fiorello La Guardia prevented the titles from being sold in Manhattan unless the covers were removed. Culture realized that they’d run their course. They’d established hot titles in the big four pulp genres (only a Spicy Science Fiction Stories was overlooked — but then Spicy Adventure and Spicy Mystery did a lot of SF stories and covers in the early forties), diversified enough to cover their losses in any situation, and sales had slacked off. Frequently, older stories would be reprinted under new house bylines. So they finally killed off the Spicies. But that wasn’t the end, by any means. At the beginning of 1943, Trojan started four new titles. Speed Adventure, Speed Detective, Speed Mystery and Speed Western Stories. Most were cover-dated January 1943. They weren’t as racy as the Spicies, but in their own way they were “fast.”

What’s fascinating here — if perhaps not directly germane to shudder pulp history — is that that the Amer/Donenfeld partnership at Culture/Trojan got its start in the early 1930s with a similar censorship-ducking dodge, as Amer defused an earlier wave of censorship aimed at his long-running girlie pulps of the 1920s:

In May 1932, Armer surrendered the gems of his line, Pep Stories and Spicy Stories, to Harry Donenfeld for printing debts owed; in like manner, Donenfeld accrued many girlie pulp titles during the 1930s… Bowing out gracefully, Armer did Donenfeld an additional service by making a ploy to deflect the censors part of the deal.

In spring 1932, the New York Committee on Civic Decency had pressured the police to arrest four newsstand owners for selling girlie pulps. At a July meeting with the Committee, charges against the four owners were dropped after Armer and other editors promised to “tone-down” their content and “pay closer heed to the proprieties” — as well as cease publication of Ginger Stories, Hollywood Nights, Gay Broadway, Broadway Nights, French Follies, and La Paree. Donenfeld continued to print La Paree in spite of this agreement, and in addition to Ginger and Broadway Nights, Armer probably had a controlling interest in Henry Marcus’ (Pictorial) French Follies and Hollywood Nights. So Armer’s pulps, which were going out of business in any case, became the sacrificial lambs, while newsstand owners were off the hook — at least for the time being.

We have established that the men who were gearing up to publish salacious pulps — including shudder pulps — in the 1930s were alert to the risks of formal censorship, and experienced in handling those risks. But what censorship activity did they actually face, and what were its effects on the shudder pulp business?

One name that comes up over and over again is that of New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. A notorious prude and blue-nose remembered at least as vividly for putting burlesque theaters out of business, La Guardia seems to have ruled mostly by bare-knuckled administrative fiat, leaving not much paper trail behind his billy-club-toting cops. Most of what survives about his pulp censorship efforts is colorful summary and commentary. I’ve compiled that in a couple of stand-alone articles, which can be boiled down here as follows:

To be continued.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please keep in mind that any moral rights the artist has remain intact under this license.

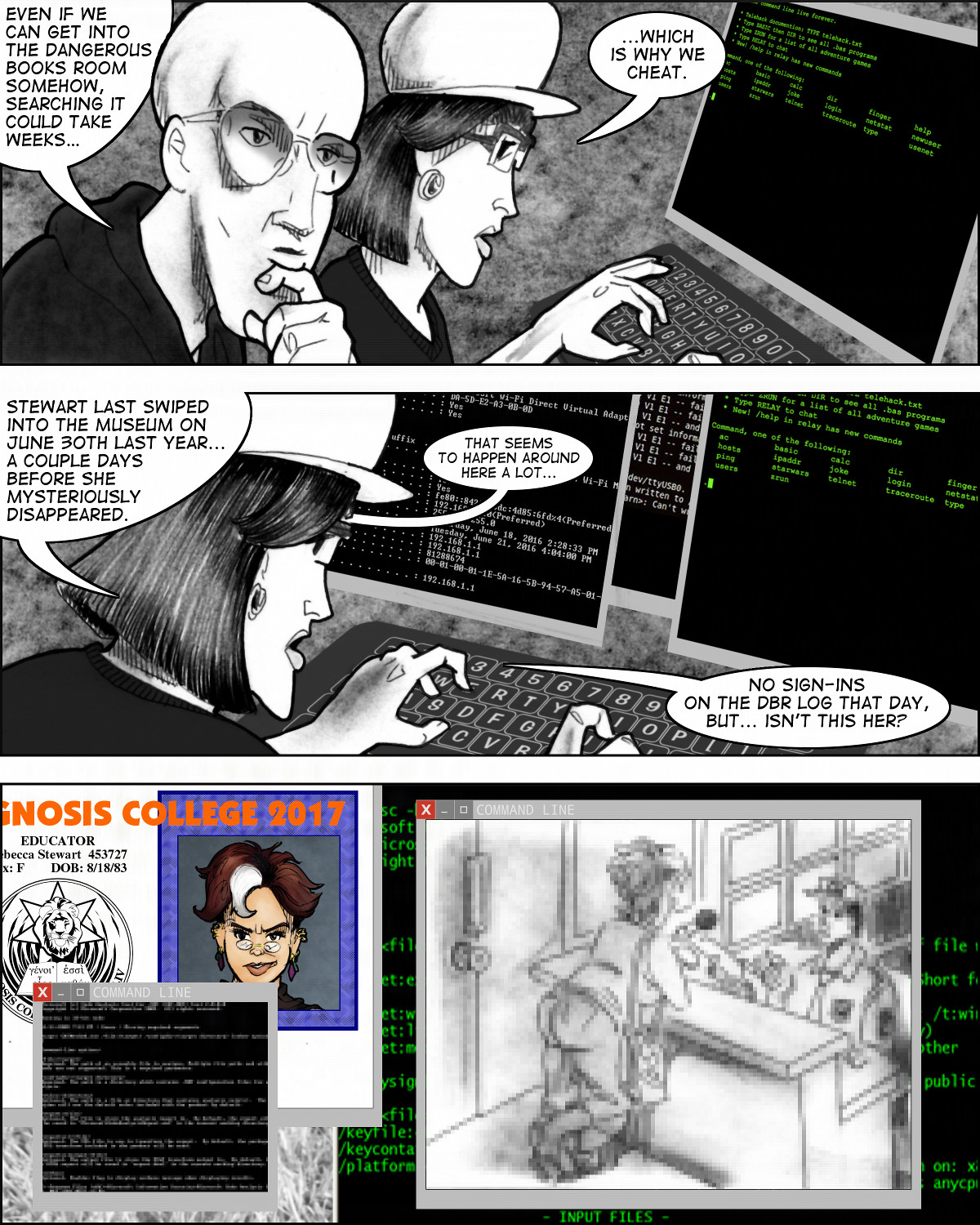

Bacchus’s research continues

There’s some interesting testimony from a Chicago-based Mrs. Grundy collected in a 1955 Duke Law journal article about comic book censorship. In The Citizens’ Committee and Comic-Book Control: A Study of Extragovernmental Restraint (John E. Twomey, 20 Law and Contemporary Problems 621-629 (Fall 1955)), Twomey specifically references a NODL-inspired church-lady boycott effort that was impaired, in part, because of the sheepishness of the volunteers who had to purchase and review weird horror and sexy titles to determine their suitability for Catholic youth. The article looks in detail at the Citizens’ Committee for Better Juvenile Literature of Chicago, Illinois, founded in 1954 to suppress comic books. But of interest here is that the committee’s primary organizer was one Mrs. Robert V. Johlic, who “had been a representative to the former Committee from the Council of Catholic Women of the Archdiocese of Chicago, with which organization she had, for six years, participated in and directed parish-wide decency crusades in cooperation with the National Organization for Decent Literature.” Johlic, a footnote reveals, is at this time actually the person who oversees the compilation of the national NODL “black list”, and NODL’s methods become the Committee’s methods as well, not limited to comic books alone:

The greater part of the Committee’s activity, however, falls under its third objective-i.e., the elimination of “detrimental literature,” which has been interpreted to include pocket-size books, popular magazines, and “girlie” magazines as well as crime and horror comic-books. The technique adopted has been that of the National Organization for Decent Literature: a wide variety of popular publications is regularly purchased; these are read by volunteers who judge them in accordance with established criteria; a list of publications judged “objectionable” is regularly promulgated; and this list is then distributed to organized teams of surveyors who visit neighborhood retail outlets and request that listed items be removed from display and not be sold. Due to the inexperience and limited number of its members, the Committee has often been forced to use NODL lists, but a volunteer reading program has been inaugurated.

This is all happening twenty years after the era of the shudder pulps, but you wouldn’t know it from the sample title Johlic makes up when talking about the challenges of her volunteer reader program:

We’ve also had a problem with some of our readers (women who volunteer to appraise the current material) who are too shy. I mean, you feel kind of silly riding home on the IC studying a copy of Nude Models or Weird Horror Tales. We’re getting around that problem by providing each of the readers with a large brown envelope to hide the magazines they’re studying.

In truth, Google doesn’t verify that any publication had used the precise title “Weird Horror Tales” prior to Johlic’s testimony in 1954, although several have since; but it’s certainly reminiscent of many shudder pulp and/or horror comic titles she would have seen and disapproved of.

The real payload of the article, though, is that it catalogs, footnoted to Johlic’s testimony, a depressing laundry list of self-appointed civic organizations who cooperated in suppressing disapproved titles, and reveals that local police stood ready to act (apparently informally in ways that don’t leave much of a trail for researchers) against any vendors who resisted this civic pressure:

There have also been instances when retailers unequivocally declined to cooperate with surveying teams. Only once, however, in its first year of operation, has the Committee found it necessary to call upon the Chicago Police Censor Bureau to exert pressure to enforce compliance as this willingness of the Police Censor Bureau to support the Committee’s activities, incidentally, is perhaps one of the Committee’s most potent instruments of persuasion.

In addition to its surveying activities, the Committee maintains close liaison with other organizations engaged in combatting “objectionable” literature, some of which look to the Committee for leadership, and others of which carry on separate campaigns. Among these organizations are tle Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Chicago Retail Druggist Association, the Camp Fire Girls, the Illinois Federation of Temple Sisterhoods, the Illinois Youth Commission, the Grandmothers’ Club of Chicago, the Association of University Women, the Chicago Region PTA’s, the Woman’s Auxiliary of the Episcopal Diocese of Chicago, the Illinois Council on Motion Pictures, Radio, Television, and Publications, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, and the National Organization for Decent Literature.

It is unclear what the Chicago Police Censor Bureau may have been or how it would “enforce compliance” with the demands of Mrs. Johlic and her blue-nosed Committee church ladies. But I think it’s fairly safe to assume that we are looking here at a snapshot of the fully-evolved tactics that the pulp industry would have been dealing with in nascent form in the late 1930s: a complex web of self-appointed civic and religious pressure groups backed when necessary by local police and government authorities acting as informally as possible because, even then, true censorship required post-hoc successful and difficult-to-obtain obscenity prosecutions and prior restraint of the sort desired by the Grundys was mostly unavailable to the law. All of this, organized separately in each of the major cities of the America: a nightmare distribution problem for any national publication, because it’s impossible (even with Johlic writing national lists for NODL) to ever get all these local bluenoses on the same page. And all of them, one way or another, able to get strong-arm support from local officials in police or municipal government.

To be continued.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please keep in mind that any moral rights the artist has remain intact under this license.

Bacchus’s research continues.

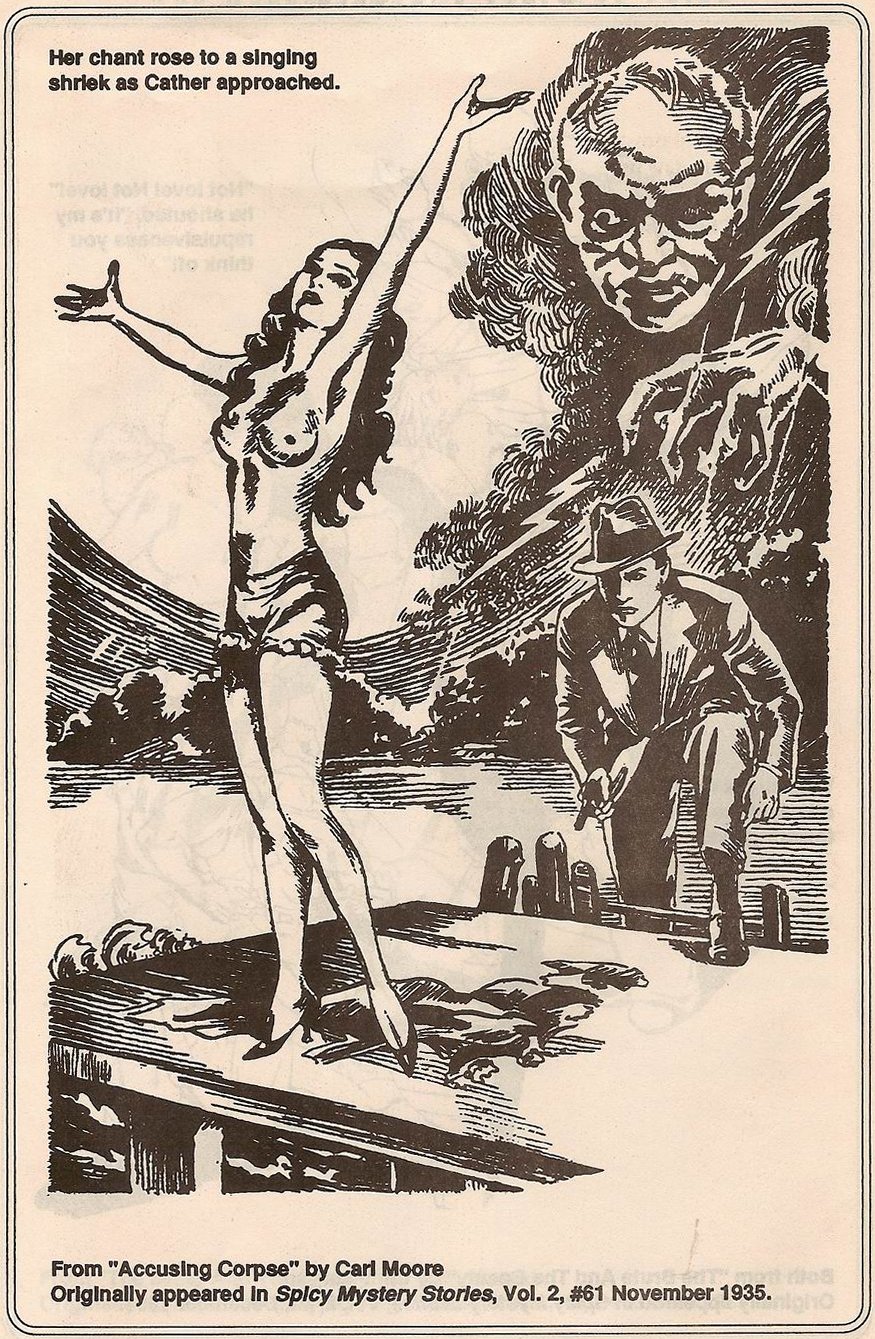

It is unclear to what extent the shudder pulps specifically were ever sold by postal subscription or relied upon mail distribution, if at all. The vituperative critic Bruce Henry suggests that they did, and he averred in his infamous 1938 critical expostulation that the horror pulps modified their artwork accordingly to cover “pelvic regions” and breasts without nipples:

“But, say mail inspectors, the illustrations must never show a completely nude wench and the pelvic region must always be obscured in some fashion. Smoke from the bubbling acid vat is usually good camouflage, as is the well-known wisp of silk. Uncovered breasts are admissible, so long as they—quaint fancy — possess no apices, as it were.”

Will Murray, in his Informal History Of The Spicy Pulps, references a specific 1938 threat from the Post Office against Culture Publication’s mailing permit. This is also the most specific reference found to the distribution of these pulps via mail subscription:

In 1938, self-appointed censors began to go after the more conspicuous sex pulps. The heat reached the Culture line, which began to cool the “heat” in its pages. The old tepid descriptions of foreplay were dropped, but the covers remained as racy as before. Culture did this reluctantly, but caved in when the Post Office threatened to remove its second-class mailing privileges, without which subscription copies could not be mailed.

Don Hutchinson goes further, in attributing the 1943 the retooling of the Spicy titles (including their renaming as Speed titles and general toning down after the infamous La Guardia explosion of 1942) in part to “fear of losing…their U. S. postal mailing privileges.” His evidence for this is not indicated. Damon Sasser likewise cites — and likewise doesn’t gesture at any evidence for citing — postal pressure as a major factor in that same big Spicy retrenchment of 1942:

By late 1942, a full court press from all sides was on the Spicy line and Donenfeld and company were forced to take action. In addition to pressure from government officials, changes were needed keep the Post Office Department happy and protect the publisher’s coveted second class mailing rate. So, in an attempt to continue publishing these successful pulps under the harsher censorship and scrutiny, covers were toned down, as was content and interior illustrations and the entire Spicy line was renamed “Speed” to eliminate the word “Spicy.”

It is well-documented that a Catholic pressure organization called the National Organization For Decent Literatature (NODL), was founded in 1938 to keep “indecent literature” “out of the community”. Its founder, one Bishop Noll, published a cartoon illustrating his intentions in a long-running Catholic publication called “Our Sunday Visitor”. Although that cartoon has proven highly resistant to being turned up in visual form, here’s a written description:

Under the headline “Now is the Time to Act” it showed a bespectacled, boyish-looking middle-aged man — a dead-on likeness of Noll, labelled “Catholic Organizations” — and in a word balloon he said, “We cleaned up the movies, but we’ve let you parasites exist too long.” He was swishing a broom, literally cleaning up a newsstand from which anthropomorphic magazines with tiny legs and feet were scurrying away. They had titles such as Nasty News, Sexy Stuff, Photo Philth, and Cartoon Dirt.

This description is in The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America (2008) by David Hajdu; and although Hajdu does not say precisely when the cartoon was published, he implies it was shortly after NODL was founded in 1938, when shudder pulps might plausibly have been on NODL’s hit list. Per Hajdu, the list was quite literal; it was offically called (at first) “Publications Disapproved For Youth”, though Noll himself called it his “black list.” It was published monthly in NODL’s magazine The Acolyte but not made public for fear that young people “looking for something bad to read” would consult it. (NODL’s “The Acolyte” — no copies of which were found on the internet — should by no means be confused with the roughly-contemporaneous 1940s amateur mimeographed “fantasy and scientifiction” magazine of the same name, some five issues of which may be found in the Internet Archive.)

At some point, NODL began working closely with the Postmaster General (also a Catholic) who by 1943 at least was barring long lists of slightly-risque pulp magazines from the mails, or at least denying their subsidized second-class mailing permits. Moreover, by that time many publishers were “cooperating” with NODL by submitting advance copies of publications for review and making close edits at church direction to avoid trouble with NODL and the post office. A newspaper article to be discussed in a future post in this series will provide a lot of detail about the situation in 1943, although it’s too late in time to shed much light on the effect of NODL’s activities on the shudder pulps in particular and it doesn’t directly address the still-uncertain question of how important subsidized mailing privileges were to pulps in general.

Although this research did not turn up any editions of the Acolyte publication or of the NODL blacklist itself, by November 1942 the NODL banned publications list in the Acolyte is said to have grown to 190 “Magazines Disapproved by The National Organization of Decent Literature.” Such a list was still being updated and included in something called the Manual Of the N.O.D.L. (a 222-page publication) as late as 1952. With the 1942 list, NODL noted:

This list is neither complete nor permanent. Additional periodicals will be added as they are found to offend against our code… They are on our list because they offend against one or more of a five point Code adopted by the NODL. [They] glorify crime or the criminal; are predominatly “sexy”; feature illicit love; carry illustrations indecent or suggestive, and advertise wares for the prurient minded.

That the NODL/postal situation was so wretched for pulps in general by 1943 lends credence to the non-specific references in the secondary sources suggesting that the shudder pulps, too, had postal permit issues, especially after 1938 when NODL was founded. However, that same source indicates that postal service revocations of 2nd-class mailing permits did not actually begin until 1942, so the matter is uncertain.

To be continued.