Bacchus’s research continues

There’s some interesting testimony from a Chicago-based Mrs. Grundy collected in a 1955 Duke Law journal article about comic book censorship. In The Citizens’ Committee and Comic-Book Control: A Study of Extragovernmental Restraint (John E. Twomey, 20 Law and Contemporary Problems 621-629 (Fall 1955)), Twomey specifically references a NODL-inspired church-lady boycott effort that was impaired, in part, because of the sheepishness of the volunteers who had to purchase and review weird horror and sexy titles to determine their suitability for Catholic youth. The article looks in detail at the Citizens’ Committee for Better Juvenile Literature of Chicago, Illinois, founded in 1954 to suppress comic books. But of interest here is that the committee’s primary organizer was one Mrs. Robert V. Johlic, who “had been a representative to the former Committee from the Council of Catholic Women of the Archdiocese of Chicago, with which organization she had, for six years, participated in and directed parish-wide decency crusades in cooperation with the National Organization for Decent Literature.” Johlic, a footnote reveals, is at this time actually the person who oversees the compilation of the national NODL “black list”, and NODL’s methods become the Committee’s methods as well, not limited to comic books alone:

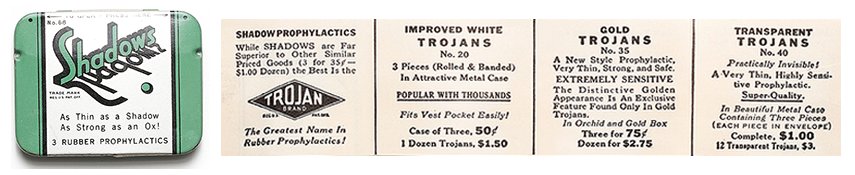

The greater part of the Committee’s activity, however, falls under its third objective-i.e., the elimination of “detrimental literature,” which has been interpreted to include pocket-size books, popular magazines, and “girlie” magazines as well as crime and horror comic-books. The technique adopted has been that of the National Organization for Decent Literature: a wide variety of popular publications is regularly purchased; these are read by volunteers who judge them in accordance with established criteria; a list of publications judged “objectionable” is regularly promulgated; and this list is then distributed to organized teams of surveyors who visit neighborhood retail outlets and request that listed items be removed from display and not be sold. Due to the inexperience and limited number of its members, the Committee has often been forced to use NODL lists, but a volunteer reading program has been inaugurated.

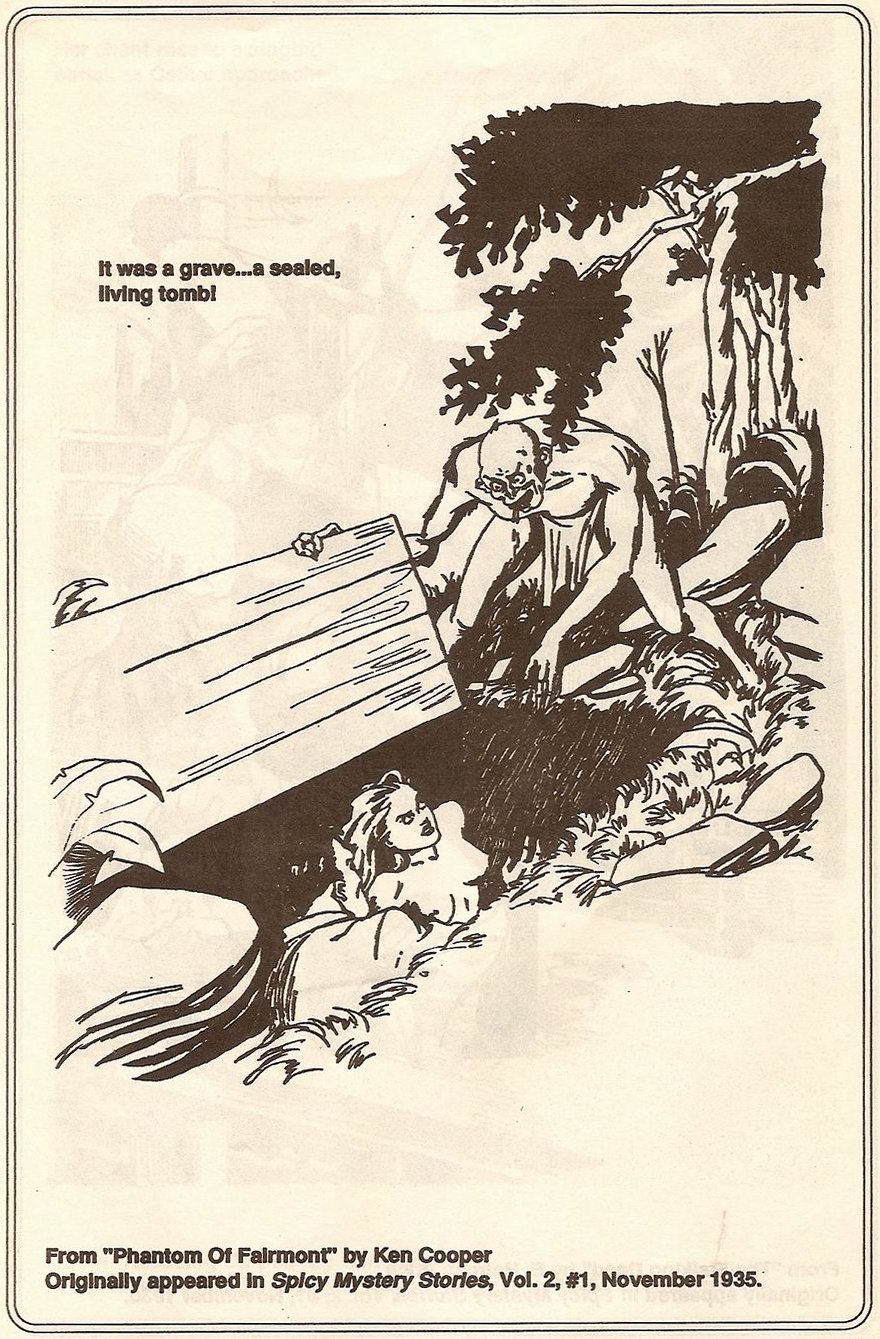

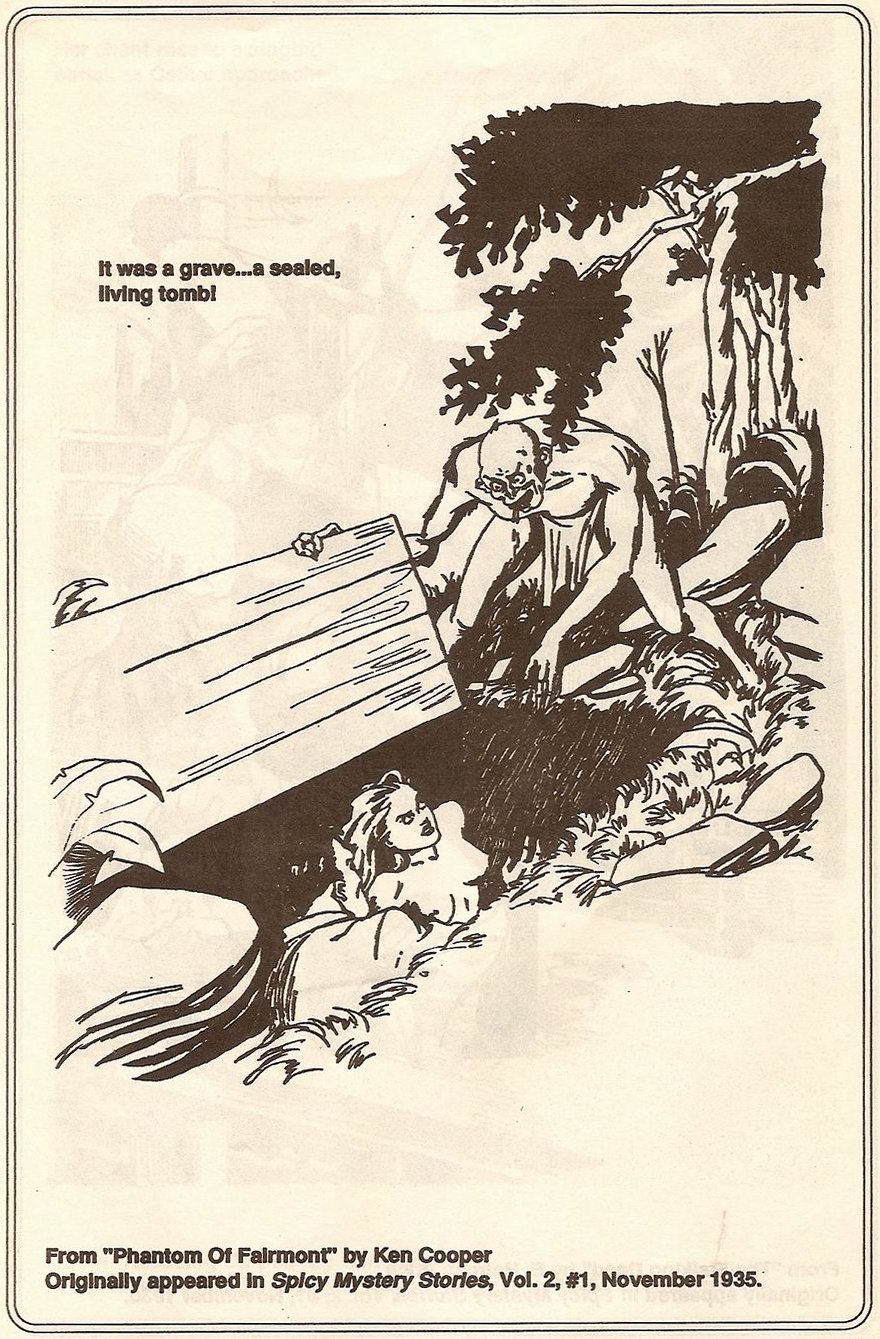

This is all happening twenty years after the era of the shudder pulps, but you wouldn’t know it from the sample title Johlic makes up when talking about the challenges of her volunteer reader program:

We’ve also had a problem with some of our readers (women who volunteer to appraise the current material) who are too shy. I mean, you feel kind of silly riding home on the IC studying a copy of Nude Models or Weird Horror Tales. We’re getting around that problem by providing each of the readers with a large brown envelope to hide the magazines they’re studying.

In truth, Google doesn’t verify that any publication had used the precise title “Weird Horror Tales” prior to Johlic’s testimony in 1954, although several have since; but it’s certainly reminiscent of many shudder pulp and/or horror comic titles she would have seen and disapproved of.

The real payload of the article, though, is that it catalogs, footnoted to Johlic’s testimony, a depressing laundry list of self-appointed civic organizations who cooperated in suppressing disapproved titles, and reveals that local police stood ready to act (apparently informally in ways that don’t leave much of a trail for researchers) against any vendors who resisted this civic pressure:

There have also been instances when retailers unequivocally declined to cooperate with surveying teams. Only once, however, in its first year of operation, has the Committee found it necessary to call upon the Chicago Police Censor Bureau to exert pressure to enforce compliance as this willingness of the Police Censor Bureau to support the Committee’s activities, incidentally, is perhaps one of the Committee’s most potent instruments of persuasion.

In addition to its surveying activities, the Committee maintains close liaison with other organizations engaged in combatting “objectionable” literature, some of which look to the Committee for leadership, and others of which carry on separate campaigns. Among these organizations are tle Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Chicago Retail Druggist Association, the Camp Fire Girls, the Illinois Federation of Temple

Sisterhoods, the Illinois Youth Commission, the Grandmothers’ Club of Chicago, the Association of University Women, the Chicago Region PTA’s, the Woman’s Auxiliary of the Episcopal Diocese of Chicago, the Illinois Council on Motion Pictures, Radio, Television, and Publications, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, and the National Organization for Decent Literature.

It is unclear what the Chicago Police Censor Bureau may have been or how it would “enforce compliance” with the demands of Mrs. Johlic and her blue-nosed Committee church ladies. But I think it’s fairly safe to assume that we are looking here at a snapshot of the fully-evolved tactics that the pulp industry would have been dealing with in nascent form in the late 1930s: a complex web of self-appointed civic and religious pressure groups backed when necessary by local police and government authorities acting as informally as possible because, even then, true censorship required post-hoc successful and difficult-to-obtain obscenity prosecutions and prior restraint of the sort desired by the Grundys was mostly unavailable to the law. All of this, organized separately in each of the major cities of the America: a nightmare distribution problem for any national publication, because it’s impossible (even with Johlic writing national lists for NODL) to ever get all these local bluenoses on the same page. And all of them, one way or another, able to get strong-arm support from local officials in police or municipal government.

To be continued.