I suspect that many young women might not be all that pleased to have a lover quote the Monster of Malmsbury at them, even in the pleasantest of afterglows. But Jill (and therefore Jill-Prime) is a scholar as well as an athlete (sexual and otherwise), and so it goes pretty well.

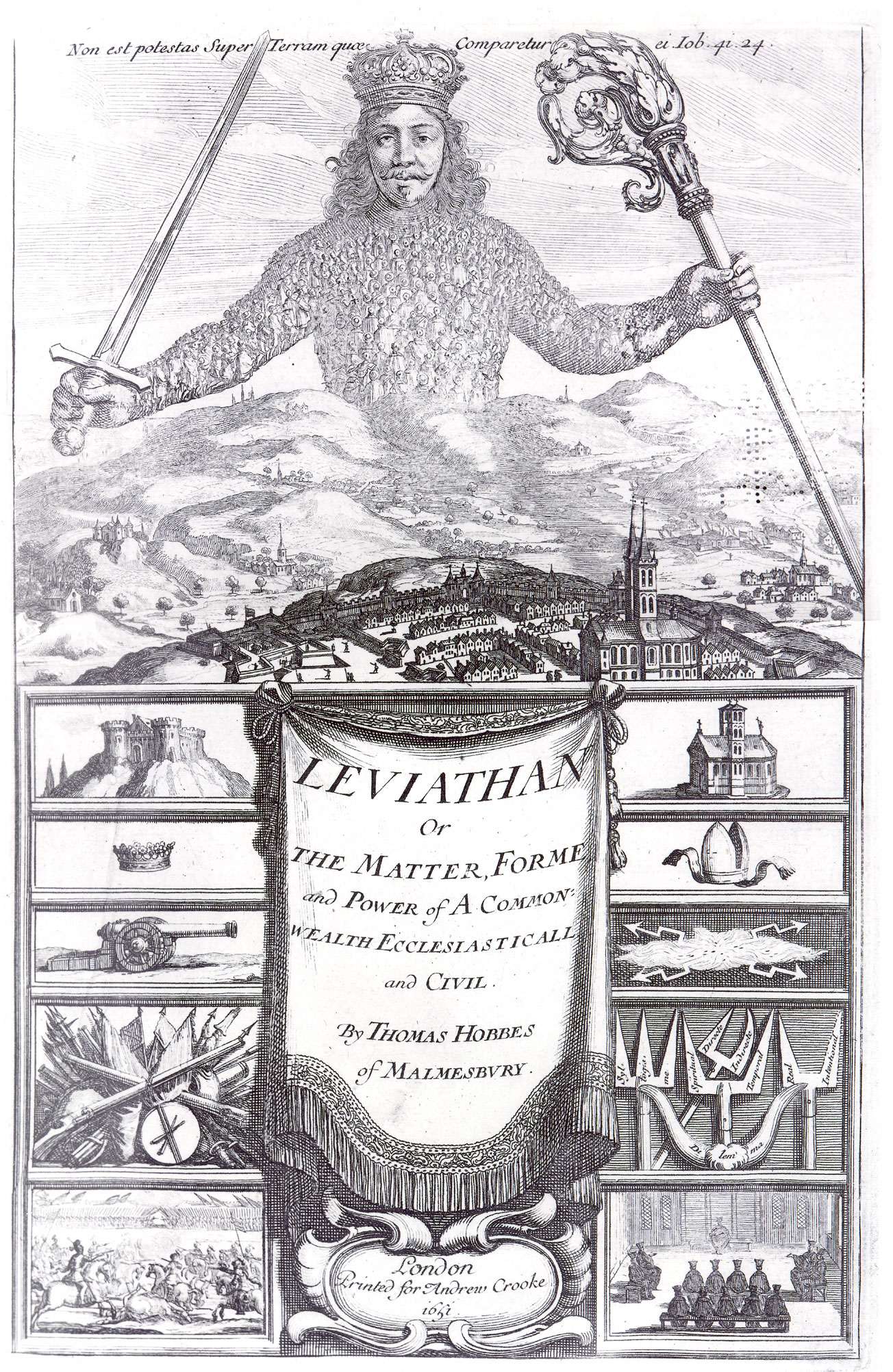

Frontispiece to _Leviathan_ (1651). Click through to see an amazing collection of politico-religious visual references in the larger image

Now you, dear reader, might well at this point be scratching your head and wondering what a 17th century English political philosopher is doing in the middle of all this erotic mad science. Well, for one thing, Hobbes is a natural go-to for the thaumatophile, because in his striking image of a political commonwealth as a sort of man-made man, he got close to the whole Frankenstein theme a century and a half early. From the introduction to Leviathan:

Nature (the art whereby God hath made and governes the world) is by the art of man, as in many other things, so in this also imitated, that it can make an Artificial Animal. For seeing life is but a motion of Limbs, the begining whereof is in some principall part within; why may we not say, that all Automata (Engines that move themselves by springs and wheeles as doth a watch) have an artificiall life? For what is the Heart, but a Spring; and the Nerves, but so many Strings; and the Joynts, but so many Wheeles, giving motion to the whole Body, such as was intended by the Artificer? Art goes yet further, imitating that Rationall and most excellent worke of Nature, Man. For by Art is created that great LEVIATHAN called a COMMON-WEALTH, or STATE, (in latine CIVITAS) which is but an Artificiall Man; though of greater stature and strength than the Naturall, for whose protection and defence it was intended; and in which, the Soveraignty is an Artificiall Soul, as giving life and motion to the whole body; The Magistrates, and other Officers of Judicature and Execution, artificiall Joynts; Reward and Punishment (by which fastned to the seat of the Soveraignty, every joynt and member is moved to performe his duty) are the Nerves, that do the same in the Body Naturall; The Wealth and Riches of all the particular members, are the Strength; Salus Populi (the Peoples Safety) its Businesse; Counsellors, by whom all things needfull for it to know, are suggested unto it, are the Memory; Equity and Lawes, an artificiall Reason and Will; Concord, Health; Sedition, Sicknesse; and Civill War, Death. Lastly, the Pacts and Covenants, by which the parts of this Body Politique were at first made, set together, and united, resemble that Fiat, or the Let Us Make Man, pronounced by God in the Creation.

And the erotic is not an element lacking in Hobbes. The passage quoted by Rob is real. It’s cited seriously by the contempoarary Cambridge philospher Simon Blackburn. Blackburn’s a delight as a writer. Not only did he administer a well-deserved intellectual spanking to theism-apologist John Polkinghorne in the pages of The New Republic a few years back, but he also gave the lecture on “Lust” as part of a series on the Seven Deadly Sins put on at the New York Public Library. It’s there that Blackburn actually quotes Hobbes. Have a look, if it’s your thing.

(Well, it’s at least my thing.)