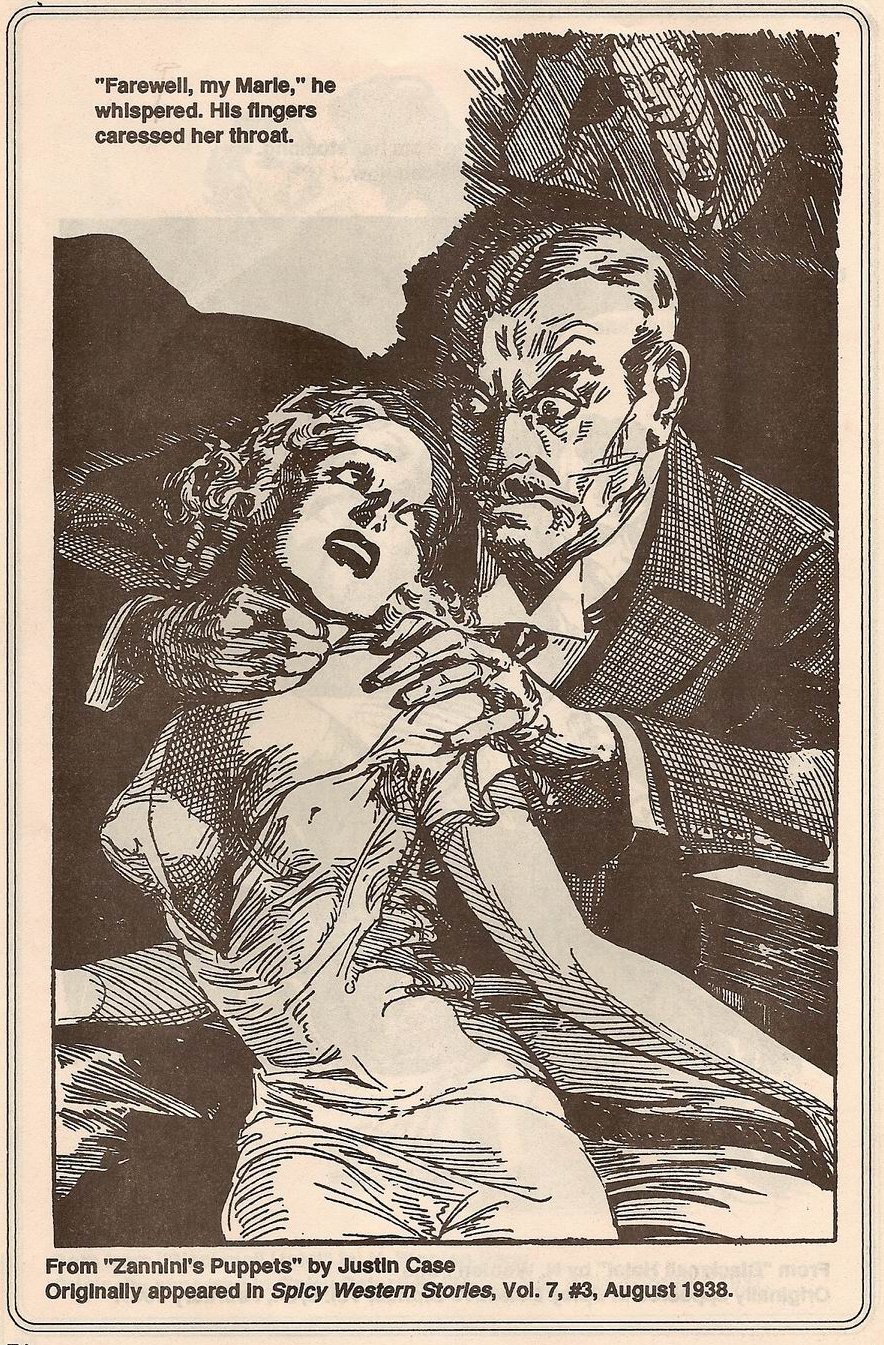

Bacchus casts some light on a side-question in the demise of the shudder pulps.

The following faint archival spoor survives to suggests that some of the Spicy titles existed in multiple versions as a presumed response to censorship pressure. This is one of those facts from which censorship can be inferred, just as the presence of an immune response to a specific virus is evidence of exposure to the virus. Here’s the email as found, followed by its heavily-degraded provenance:

From: “Phil Stephensen-Payne”

Date: 17 June 2006 13:08:39 GMT+04:00

To: fictionmags@yahoogroups.com

Subject: [fictionmags] Variant Spicies – a new can of worms

Reply-To: fictionmags@yahoogroups.com

Thanks to the intervention of chum Curt P., I have acquired a batch of PEAPS mailings from the early 1990s and will be indexing/describing these to the list in due course (i.e. some timein the next 20 years). Much of the material has been overtaken by events, but one article caught my eye as it related to my current main project (the Crime Fiction Index) and contained some information that was new to me. Sadly it also opens a whole can of worms so I was hoping the chums might be able to help me out.

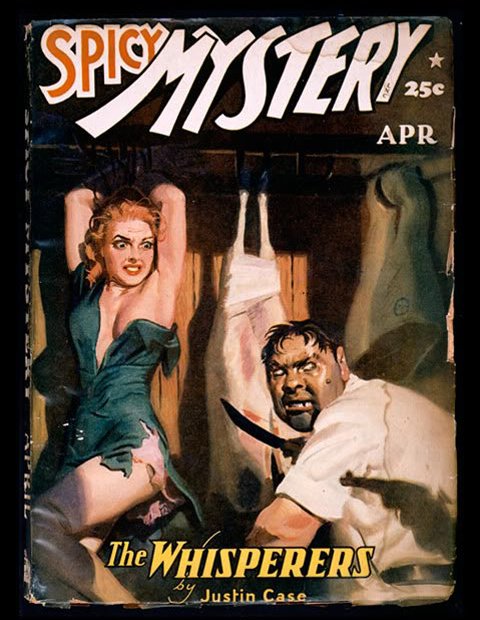

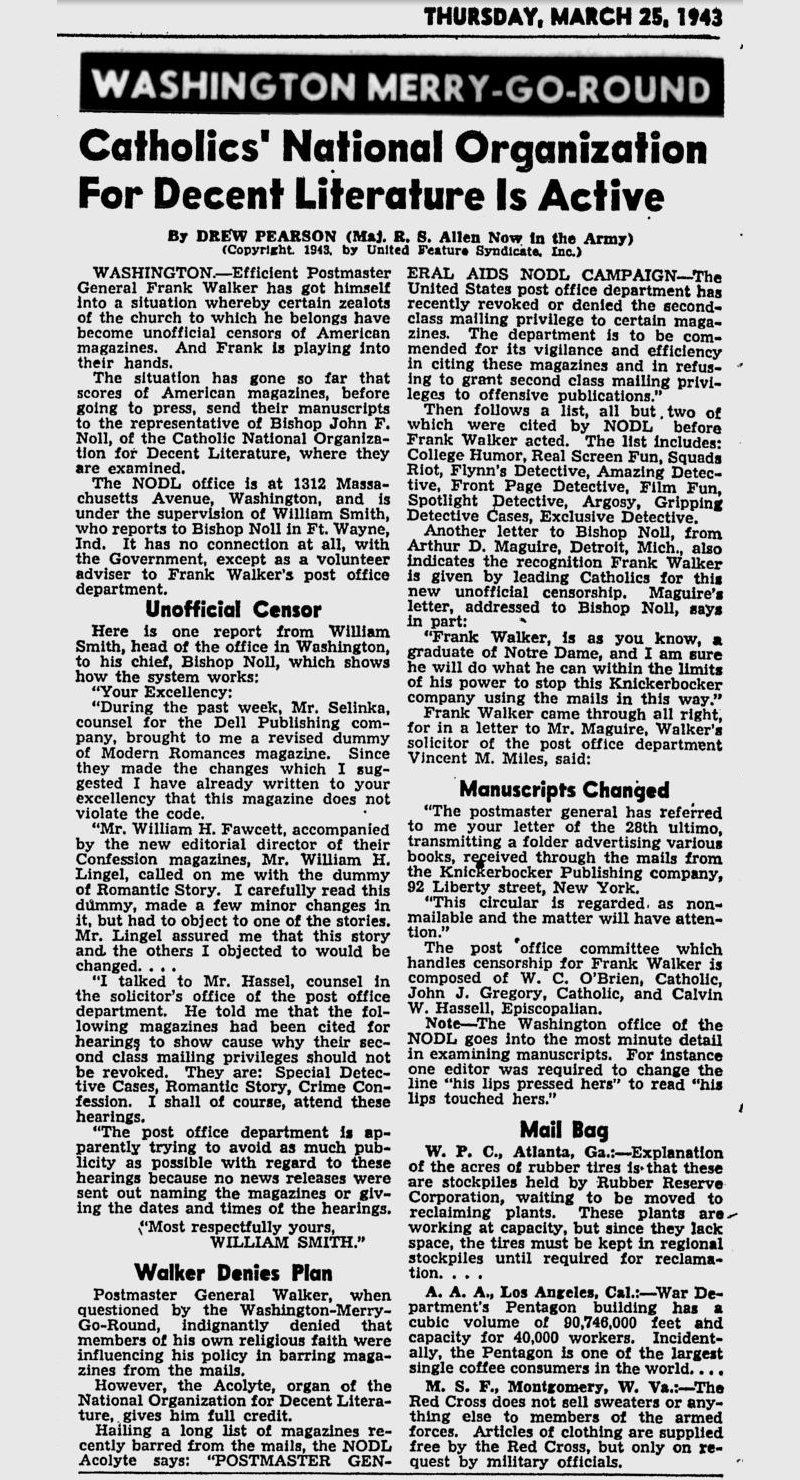

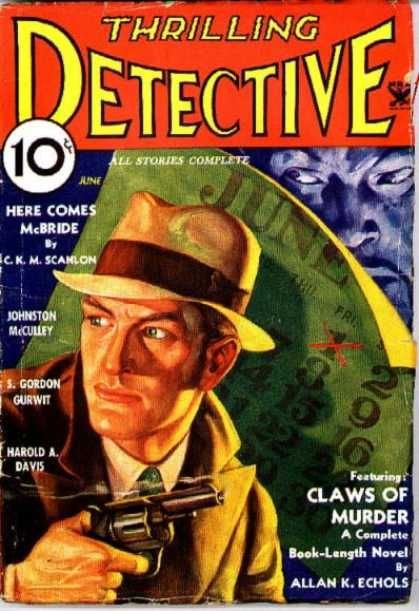

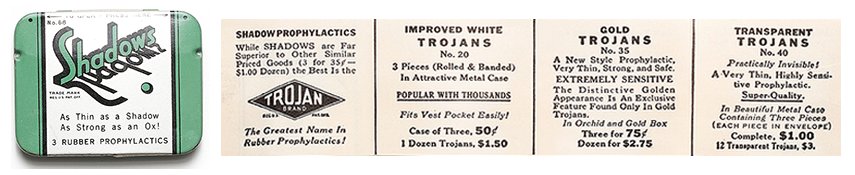

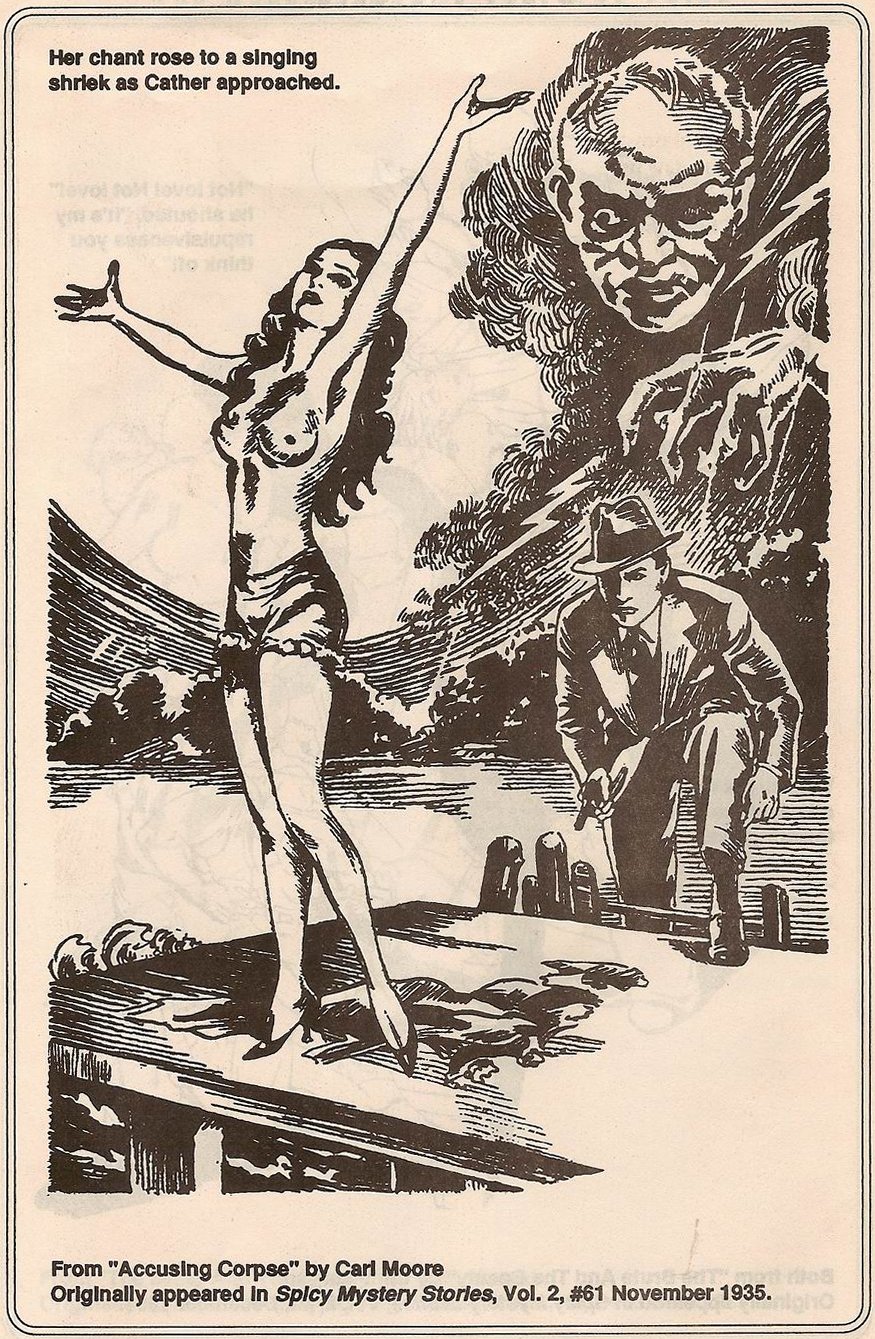

The article is “Starred and Unstarred”, in three parts, by Glenn Lord, Dan Gobbett, Jerry Page & Jerry Burge. This article discusses the censorship that occurred in some issues of the SPICY pulps during the late 1930s. I’m sure most chums are aware of this but, just in case not, the basic story is that, for a while around 1935-1937, each of the Trojan SPICY titles (ADVENTURE, DETECTIVE, MYSTERY & WESTERN) appeared in “starred” and “unstarred” versions. The “starred” versions are toned down / censored both in terms of the illustrations and of the text. So far, so familiar, but Glenn Lord’s part of the article revealed something I had not heard of before – that in some of the starred issues, stories were not only censored but were also, at times, presented in a different order (not too exciting) or even dropped completely and replaced by other stories! There are therefore an indeterminate number of issues of these magazines which exist in two versions which actually have different contents (Glenn lists three issues of SPICY DETECTIVE and five of SPICY ADVENTURE with different contents and Page/Burge illustrate the ToCs from the two versions of one issue of SPICY DETECTIVE with the contents shuffled, but each suspects there are more issues as yet unrecorded). Needless to say I am extremely interested in trying to pin this down (for DETECTIVE and MYSTERY at least) for the Crime Fiction Index, not least to sort out whether the issue lists I have are for the starred or unstarred versions (or a mixture of both). I’ve e-mailed Glenn to see what information he can supply but, meanwhile, I’d love to hear from any chums who have copies of any of these pulps (or information on the variations).

Regards, Phil S-P.

This email was included as a file named “spciy note.txt” in an 80.5GB torrent of pulp-related material that has the unique torrent hash “ba32ca44c77c95c876272510ca8099e1fdda3408”. (Verbum sapienti sat est.) According to the same Phil S-P’s Fiction Mag Index, all three parts of the Starred And Unstarred article appeared in the April 1990 issue of Spicy Armadillo Stories, which sadly but unsurprisingly does not appear to be readily available on the web.

See also: REH Splashes the “Spicys” — Part V by Damon C. Sasser:

Hoping to quell some of the criticism coming from moral squads and local governments that were on the warpath to clean-up the sexual titillation prevalent in the spicys, other pulp titles and comic books, Donenfeld and his editors embarked in 1936 on a mission of self-censorship. The company began creating two versions of three of their four Spicy magazines (for some unknown reason, a censored version of Spicy Mystery was not done), each version was marked with a five point star on the cover near that issue’s month. A boxed star meant a cleaned-up version of the magazine, while no star or an un-boxed star indicated the spicy version. In the tamer version, the text was less spicy and the women’s “charms” more concealed. The self-censorship effort was stopped at the end of 1937.

But what determined where the censored, boxed star version was sold? Was it created for the Bible Belt and more conservative states? Was the censoring done to appease the Post Office? But were subscriptions actually sold? (The magazines had no subscription information in them.) Why were the dual issues only restricted to 1936 and 1937? Why was Spicy Mystery, the most notorious of the Spicy line, spared from being censored? Due to the passage of time and lack of surviving business records, we will likely never know the answers to these questions.