A twisted institution like the State Home for Wayward Girls has obvious cinematic precedents in the women in prison film and, more grimly, in movies like Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS, but it also comes out of a certain dark place with deep roots in my imagination, for I have always had a fear of something that might be described as “the confining institution in which no one gives a fuck about you.” So while the scenes that take place in the State Home might be a twisted form of erotica, they might also be a product of long-standing fears. (Perhaps that’s what makes twisted erotica possible.)

As a child, I remember as soon as I acquired the concept of “orphanage” I remember being afraid, really afraid, that if I didn’t behave myself, I might find myself consigned to one. (I was good. Believe me, I was good.) As soon as I understood what a “prison” was I was afraid of it. Not just of finding myself in one, but of being sent to one and forgotten, so that that I would never be let out. Don’t even get me started on how repulsive it was to have to register for what the U.S. government euphemistically calls “Selective Service.”

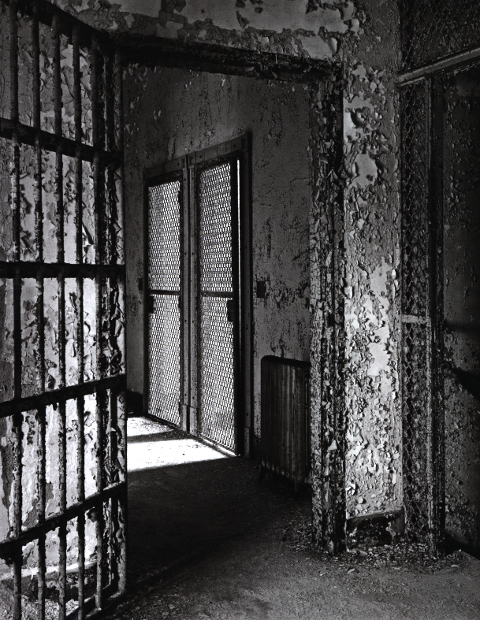

But perhaps, even though the State Home is technically more of a reformatory or juvenile detention center, the institution after which it is most modeled is the insane asylum. In part, it’s because they are such total institutions where scary things go on. I own a coffee-table book of photographs by Christopher Payne called Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals, which consists exclusively of pictures taken at, or of, abandoned insane asylums. The photographs are all beautifully executed. Some of them haunt me. Some of them downright scare me.

And there’s something particularly mad science about the insane asylum that a prison or the even the Army doesn’t have. Because while weirdos like me might fantasize mad science, it seems as if twentieth century psychiatry has been busy figuring out ways to practice it, and on many of society’s most marginal and vulnerable individuals at that. Mad as I am, I’ve never come up with the idea of shooting high voltages through people’s skulls, or lifting up their eyeballs and chopping up parts of their brains with an icepick, or insinuating “memories” of Satanic ritual abuse into the minds of unhappy people, in the name of therapy.

Small wonder that I find a mad science connection to madness.

Inane asylums also figure importantly in the sort of fantastic literature that was the matrix in which my early strangeness was nourished.

Nobody can ever keep track of these people, and state school officials and census men have a devil of a time. You can bet that prying strangers ain’t welcome around Innsmouth. I’ve heard personally of more’n one business or government man that’s disappeared there, and there’s loose talk of one who went crazy and is out at Danvers now. They must have fixed up some awful scare for that fellow.

–H.P. Lovecraft, “The Shadow over Innsmouth” (1931)

It was with a strange mixture of fear and pleasure that I discovered that “Danvers” was a real and not a fictional place: the Danvers State Insane Asylum in Massachusetts. And it was plenty creepy-looking:

So it was an obvious model for the “old building” at the State Home site in which Strangeways conducts his terrible experiments.

Danvers would become the setting for one of my favorite minor horror movies, Session 9, about a crew of workmen hired to remove the asbestos from the abandoned asylum. Things go very wrong, predictably.

And thus it’s perhaps just as predictable that things will go wrong with Strangeways.