I didn’t construct this scene in Study Abroad with all that much foresight; it was just something that boiled up from the darker regions of my mind and onto the page. On looking back after writing I did think “By Great Cthulhu this one will annoy all sorts of folks.” (Among other things it is quite the act of blasphemy, against at least two major religions. Perhaps I shall soon be facing prosecution in Ireland.) I toyed with the idea of taking it out, but eventually decided that it made more sense to leave it in. Not only does it make a significant point (and prefigure menaces that will become more manifest in later scripts), but it draws on its own significant artistic tradition, whether people like it or not.

I have speculated before about the existence of an inner connection between sadistic spectacle and a certain kind of spirituality. And you needn’t take my own word for it; you can attend to those of Thomas Aquinas, that celebrated Saint and Doctor of the Church, who tells us in all seriousness “Beati in regno coelesti videbunt poenas damnatorum, ut beatitudo illis magis complaceat.” (See one F. Nietzsche, Zur Genealogie der Moral, I.15.) If that sentiment doesn’t disturb you more than anything else you see in the post, you might want to sit down and meditate quietly on your values for a while. (It’s possible that Nietzsche didn’t get the wording quite right but he was dead-on correct in diagnosing the sentiment. As he will remark later on, “…alle Religionen sind auf dem untersten Grunde Systeme von Grausamkeiten.”)

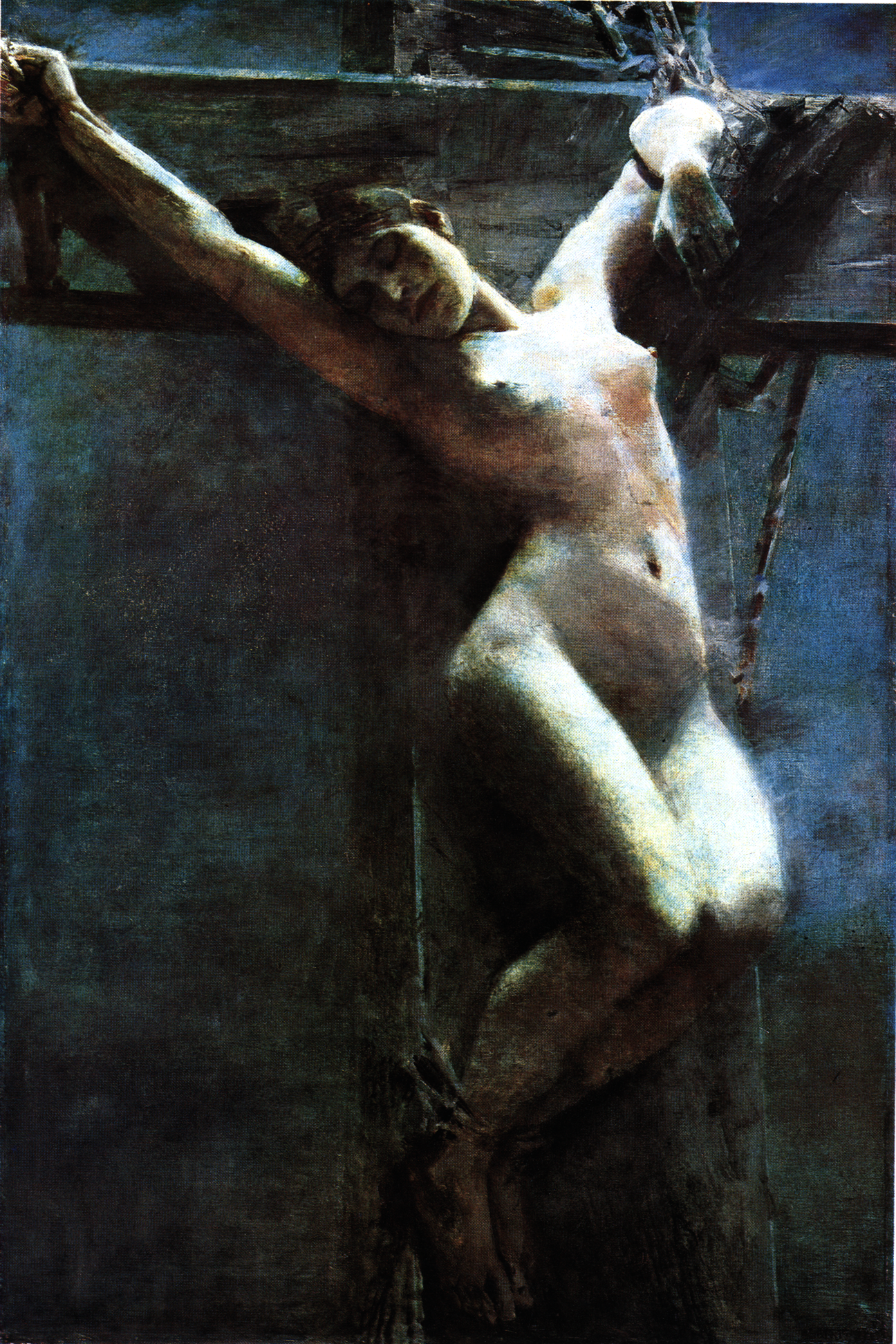

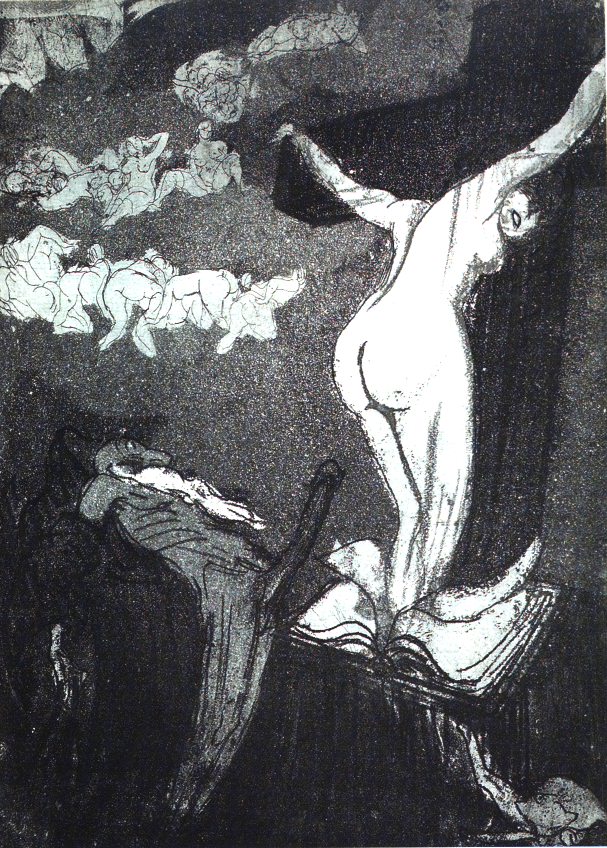

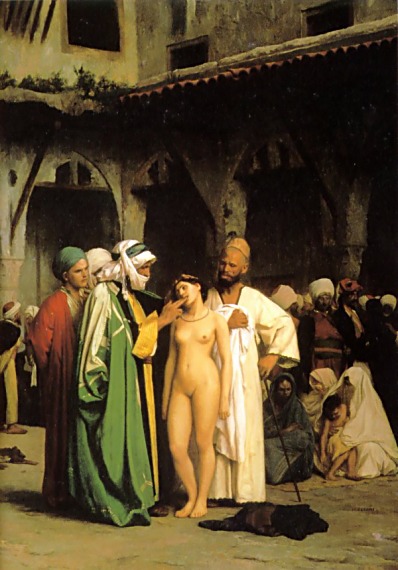

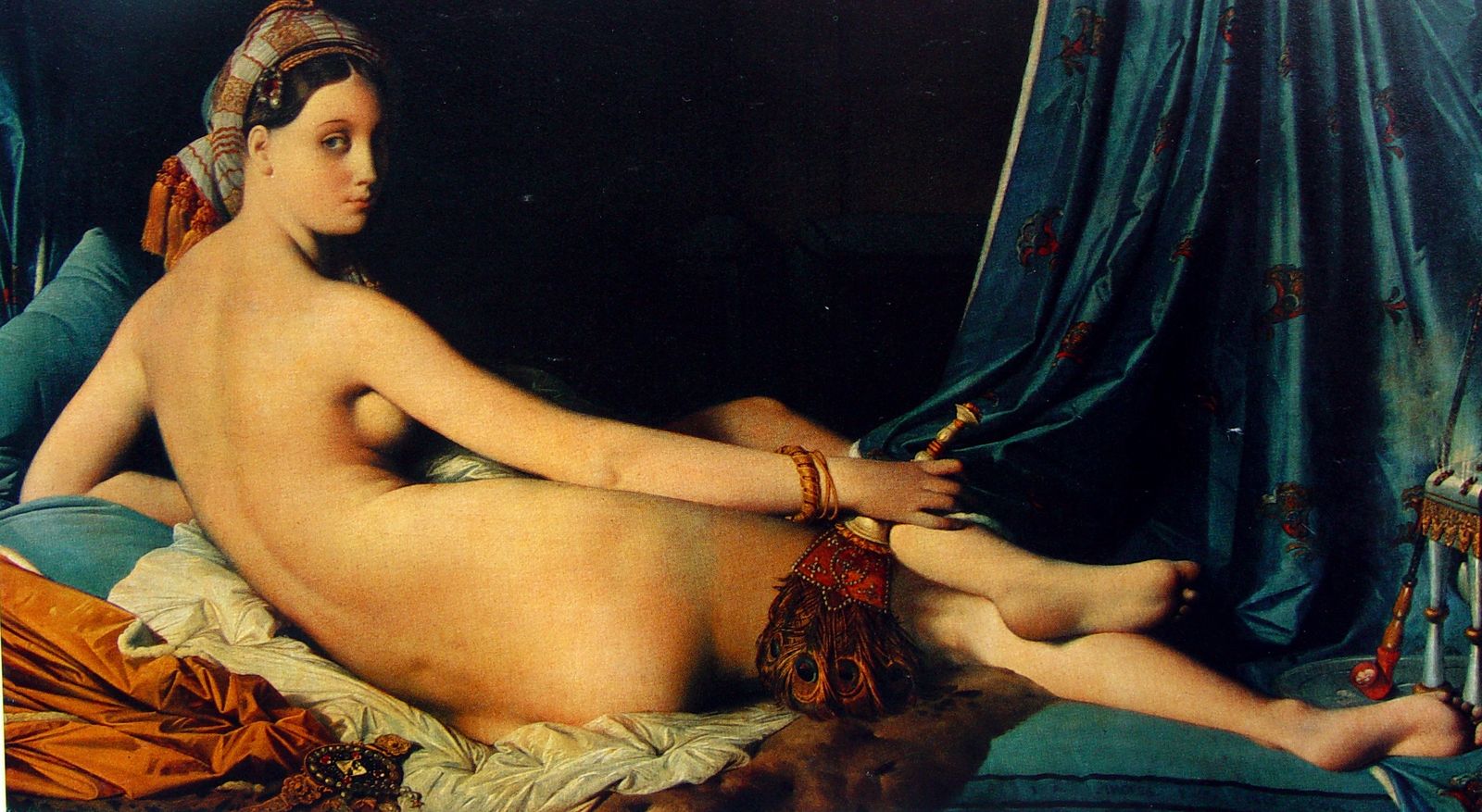

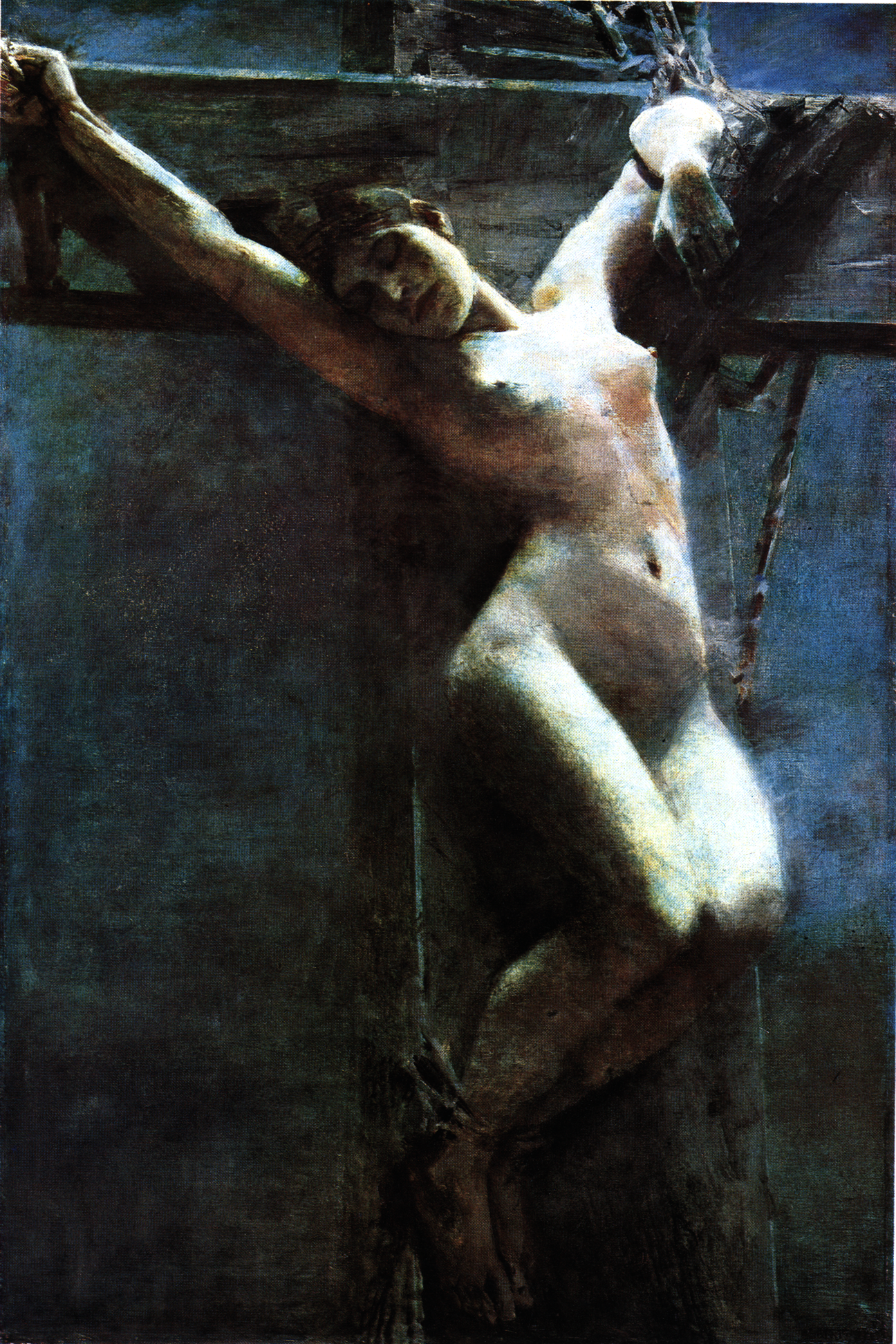

In an event, you can certainly look into art history and find images similar to what appeared in my scene, whether as images of pious martyrdom or voluptuous cruelty (or, if I am right if I am right about the connection between the two, both).

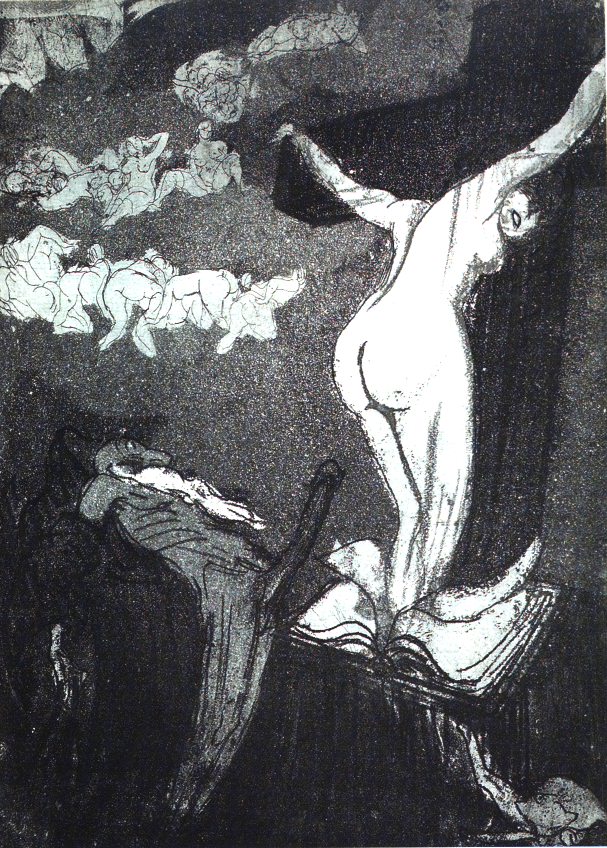

Since there is probably no image quite as broadly distributed as that of crucifixion in Europe (Catholic Europe especially), it is hardly surprising that it will crop up all over the culture, for example in the rumor of the Crucified Canadian that was common in British trenches in the First World War. And since it is a sacred symbol, it is hardly surprising that there were illustrators willing to repurpose it for especially transgressive pornographic purposes, e.g.

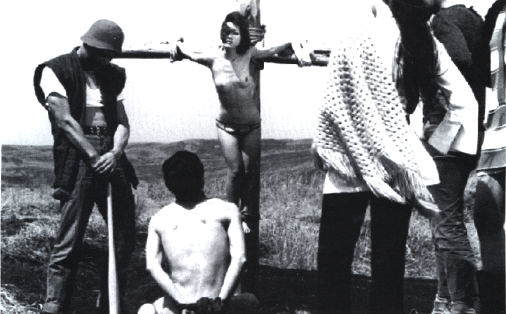

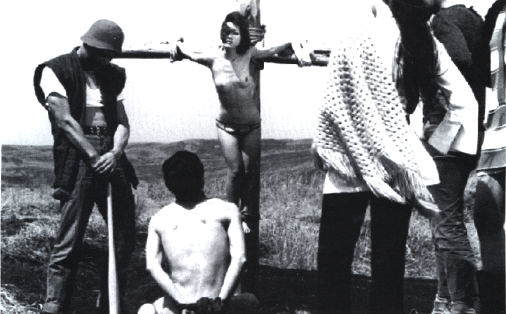

And that the idea would spread far in time, eventually all the way to Japanese cinema.

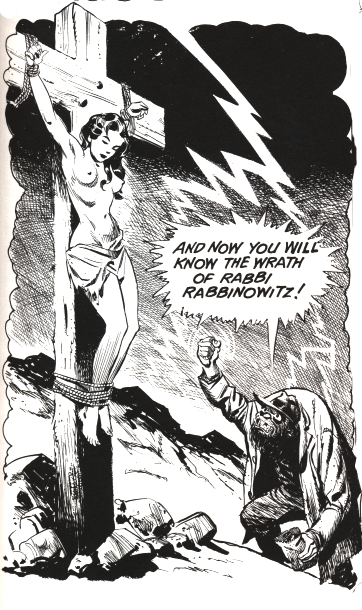

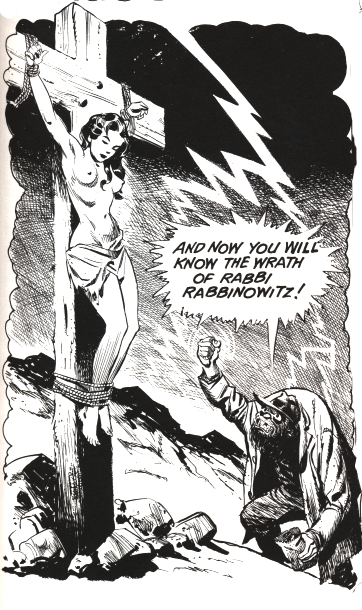

And, in the end, become an object even of eroticized satire, drawing on the artistic conventions of anti-Semitic caricature as in this part of Phoebe’s “backstory” from The Adventures of Phoebe Zeit-Geist. (And yes, based on the context in which the image appears, I really am sure it is meant as satire.)

And so now, with the help of Springer and O’Donoghue, I’ve blasphemed against all the Abrahamic religions.

But if I can’t be transgressive, then what am I doing here?

The unnamed girl at the piano was played by Kym Malin, who was Playboy’s Miss May 1982. As I rolled her famous Weird Science scene around in my head I hit upon a backstory for her indignity: the gods themselves decided they wanted Kym as a plaything, and so that’s why supernatural winds stripped her naked and sucked her up the chimney.

The unnamed girl at the piano was played by Kym Malin, who was Playboy’s Miss May 1982. As I rolled her famous Weird Science scene around in my head I hit upon a backstory for her indignity: the gods themselves decided they wanted Kym as a plaything, and so that’s why supernatural winds stripped her naked and sucked her up the chimney.