(This is the first part of a short essay.)

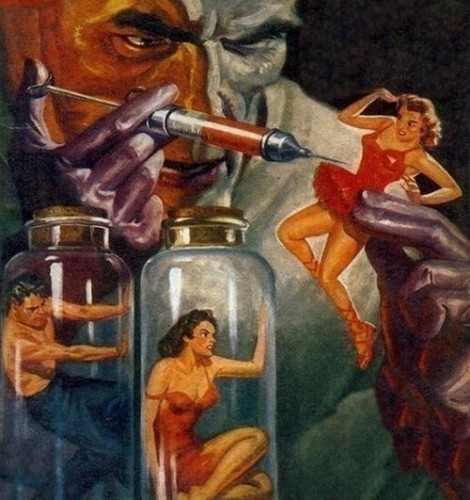

Utter the phrase “female experimental subject in mad science” and I’ll bet that the first image that nine out of ten hearers conjure in their minds would be something like this:

(Found at Storybook Whorehouse.) Call her the Distressed Damsel. A beautiful woman captured and restrained (or sedated), stripped either completely or at least down to scantily clad, and then forcibly subjected to some obscene, perversion of nature technological intervention. The Distressed Damsel might be doomed to perish or to some fate even worse than that (as a way of establishing the wickedness of an antagonistic mad scientist), or might exist for the purpose of being rescued by a hero. As John Villalino has pointed out, many mad science stories will contain at least one Distressed Damsel of each type. One goes to first to her mad science doom as a way of establishing the antagonist (and, of course, allowing the audience to enjoy the titillation of watching her get bound, stripped, and mad-scienced up), while the other will be rescued as a way of bringing the story to what most viewers would find a morally satisfying conclusion.

I won’t deny that the Distressed Damsel story has its charms, but somehow I find myself even more excited by a rather different kind of story, one built around a kind of experimental subject I’ll call the Kitty Carroll. An image for her:

That’s Kitty Carroll, being turned invisible in the 1940 film The Invisible Woman. Something important to note about this female mad science subject: She might be naked (albeit demurely behind a screen as this is a 1940 movie), but she’s not in restraints, she hasn’t been kidnapped, she hasn’t been sedated. She’s here as a volunteer, answering a newspaper classified ad. Her response to the mad science? I want a part of that! As I wrote about her two years ago:

Let’s reflect on what Kitty has implicitly gone for here: “So, you want me to take off all my clothes, step into this machine that has hitherto never been tested on a human being, zap me with heaven-knows-what, and turn me invisible? Sure, I’m game!”

I think I’m in love.

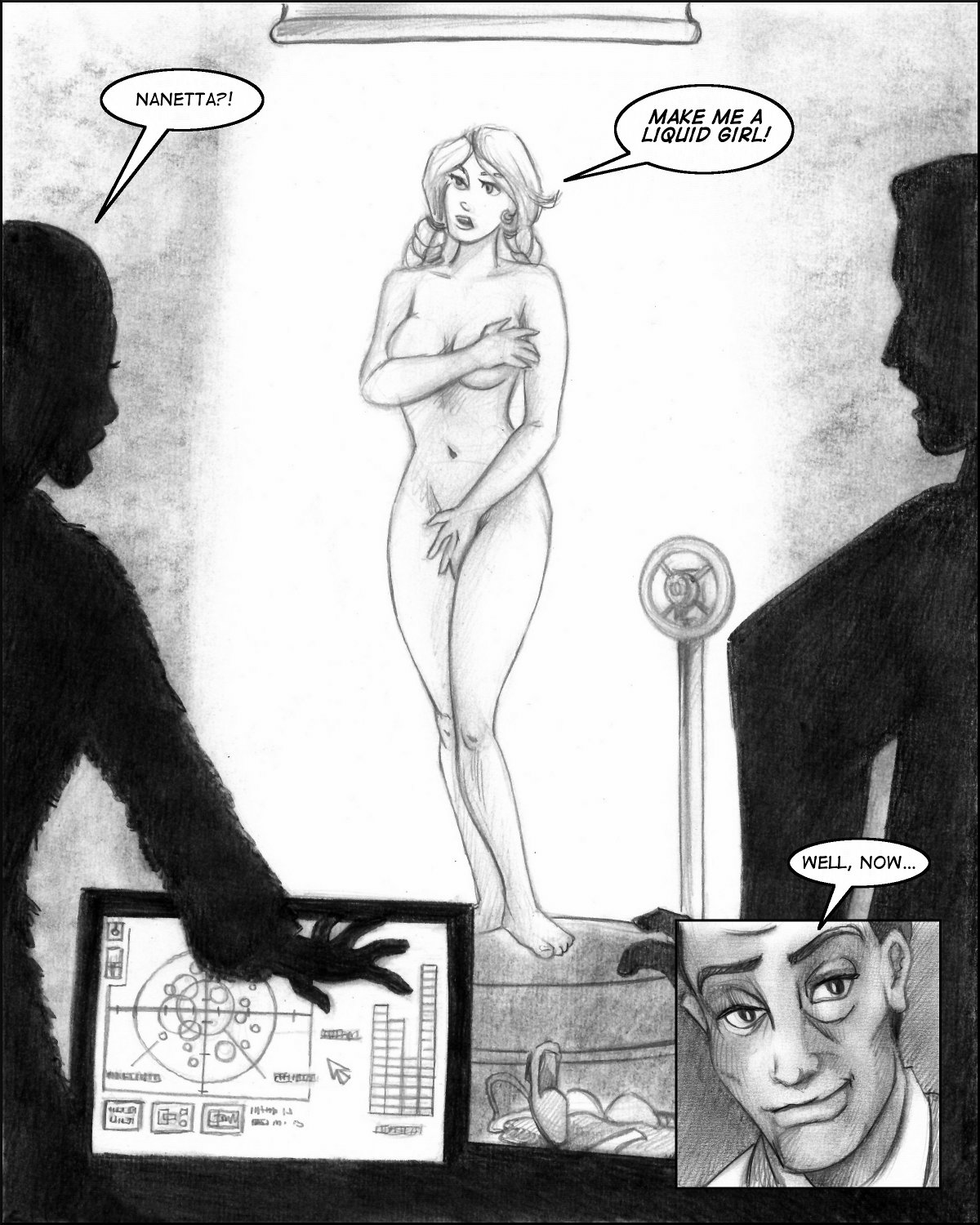

And dammit, I think I’m still in love. The kind of fiction I create shows a longing for Kitty Carrolls wherever I can find them. The first instance that Lon illustrated for me in the first chapter of The Apsinthion Protocol:

Nanetta Rector embraces the mad science rather than fleeing from it. As will her friend Moira Weir. As will all four of the heroines of Study Abroad, albeit with a little pharmacological boost from Dr. Strangeways. Kitty Carrolls all.

I wish I could find more examples of Kitty Carrolls in fiction created by professionals — perhaps the paucity of such are a good reason for making my own. To be sure, I can think of a few. Janice Starlin in Roger Corman’s The Wasp Woman might be an example of one — she pushes really hard to get the mad science youth-making transformation tested on herself. I’ve suggested before also that one the most erotic things I’ve had about Invasion of the Bee Girls is not so much a scene (hot as the transformation scene is) as a thought: that Dr. Susan Harris, the lady mad scientist and head Bee Girl, is herself a Kitty Carroll, that everything we saw being done to Nora Kline as a Distressed Damsel — getting naked, getting irradiated, getting smothered in goop and covered in bees, and transformation into some sort of seductive, lethal transhuman — Dr. Harris must have done to herself at some point to become what she is by the time the movie begins. Talk about embracing the mad science!

I think perhaps I’m in love in a way that will probably be the end of me, but it will be worth it.

And why am I so in love with Kitty Carrolls? Tomorrow I get to embarrass myself with psychological speculation.