The year 1940 was one of great change in Canada. A constitutional amendment allowed the government to introduce and adopt the Unemployment Insurance Act. Parliament passed the controversial National Resources Mobilization Act authorizing home defense conscription for 30 days, a term that over time stretched to cover the duration of the Second World War. In Quebec, women won the right to vote.

And, with the passing of the War Exchange Conservation Act, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King became the unwitting father of the Canadian pulp magazine industry.

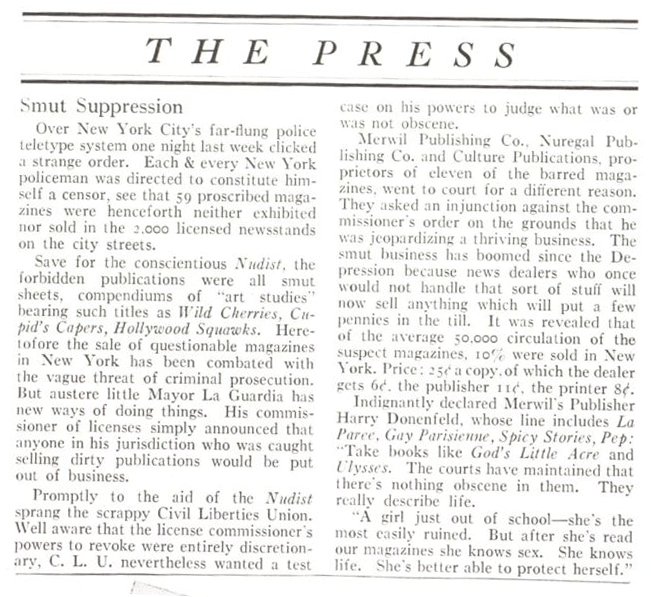

According to Carolyn Strange and Tina Loo, the War Exchange Conservation Act was designed to preserve Canada’s balance of trade with the United States. To preserve this balance, Canada banned the import of a broad range of nonessential items from the U.S., including such luxury items and diversions as cocoa paste, champagne and pictoral postcards. It also targeted what had become for many people not a luxury, but an essential distraction from the harsh realities of everyday life: the pulps. The language of the act specifically prohibited the import of any periodical publications featuring “detective, sex, western and alleged true or confession stories.”

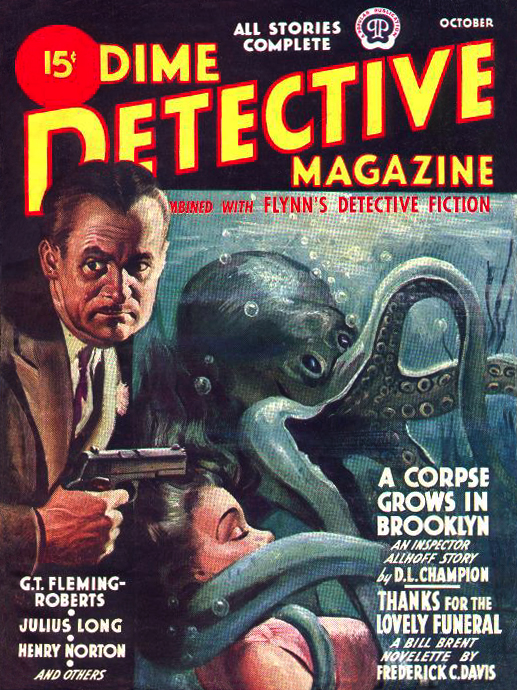

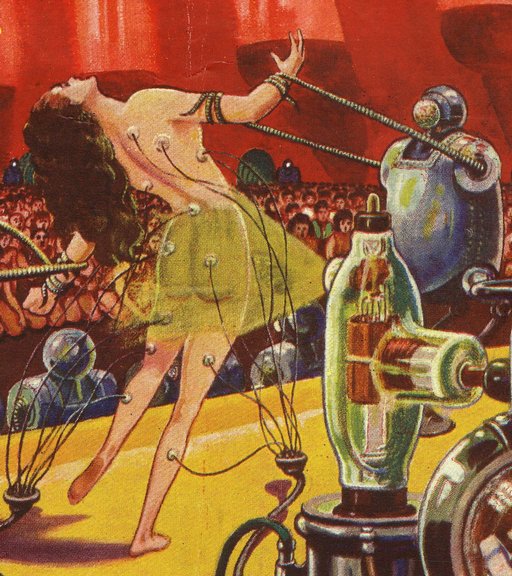

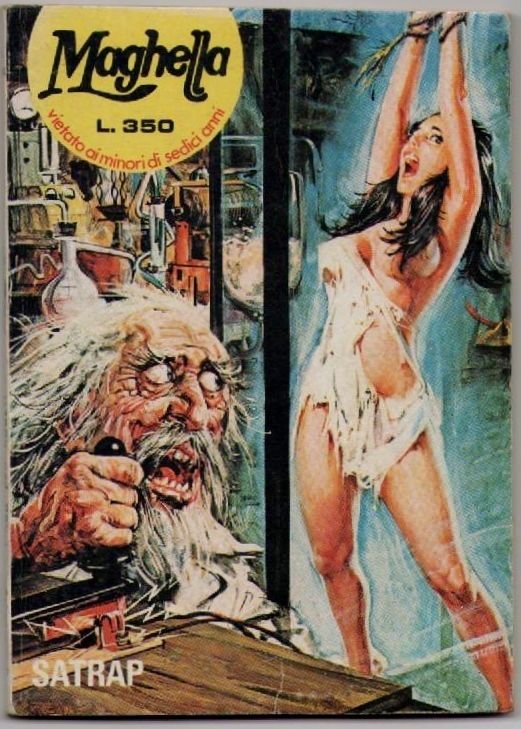

Detectives. Sex. Westerns. Confession stories. These were topics that sold magazines, and Canadian publishers knew it. People would still want their weekly fix of grisly murder, winking pin-up girls, thundering hooves and vicarious heartbreak; if the Americans could no longer supply it, someone else would have to.

As the December 1940 issue of the industry magazine Canadian Printer and Publisher put it: “Certain branches of the printing industry stand to benefit as a result of the measures announced in the House of Commons on Dec. 2 by Hon. J. L. Ilsley, Minister of Finance. Included in the long list of prohibited imports from non-sterling countries, principally the United States, are certain kinds of periodical publications such as those classified as detective, sex, western and confession stories.”

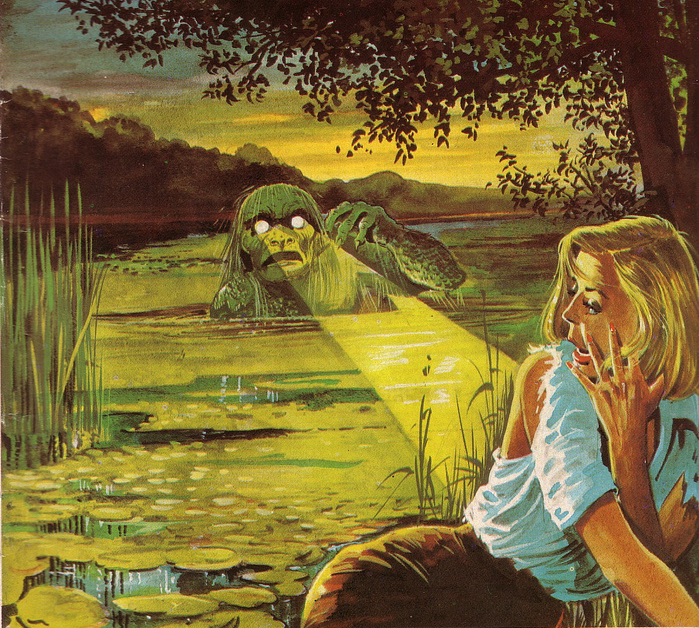

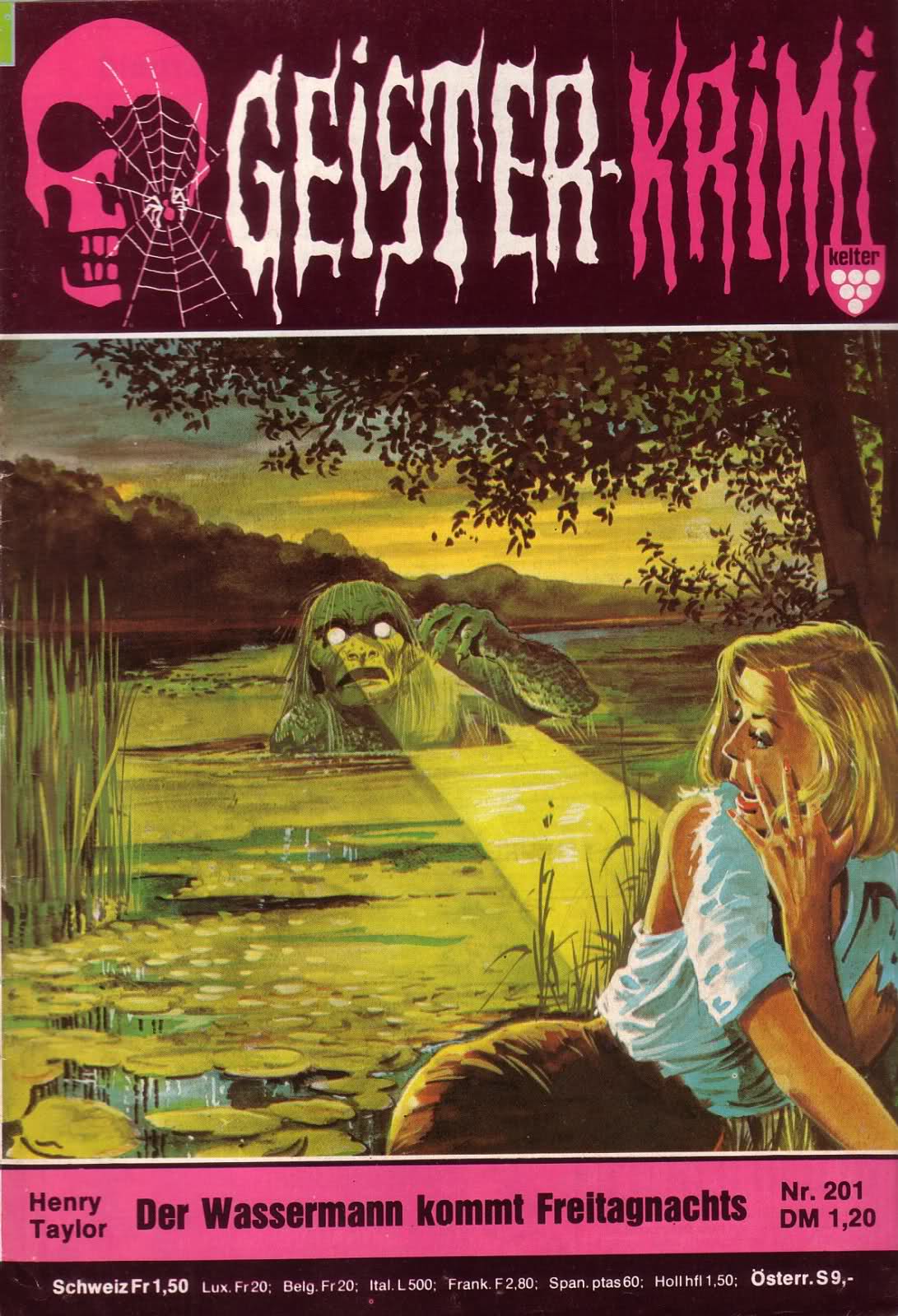

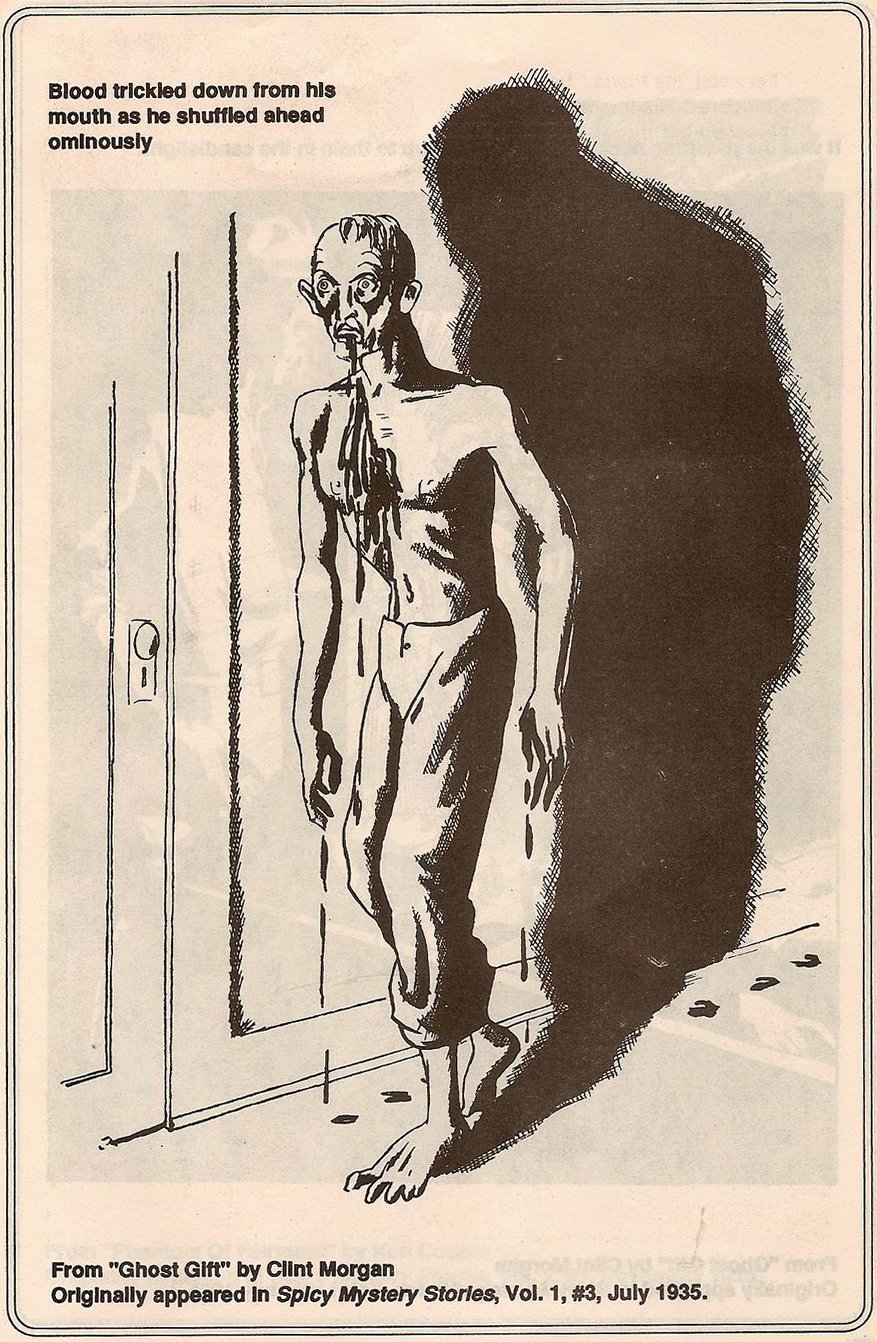

There were those words again. Detectives. Sex. Westerns. Confession stories. Add a smattering of other genres (science fiction, horror and the “northerns” — adventures that transposed the action of the western to Canada’s far north and swapped cowboys for Mounties), and you had what would become the stock-in-trade for Canadian pulp publishers.

In the beginning, Canadian publishers relied on submissions from U.S. authors, or even pirated copies of stories published in U.S. magazines. After all, Canadian audiences would recognize these authors, many of whom had developed a loyal following during the period when American pulps were readily available. The readers knew which writers penned the goriest murders, the most risqué love affairs and the most bloodcurdling horror stories.

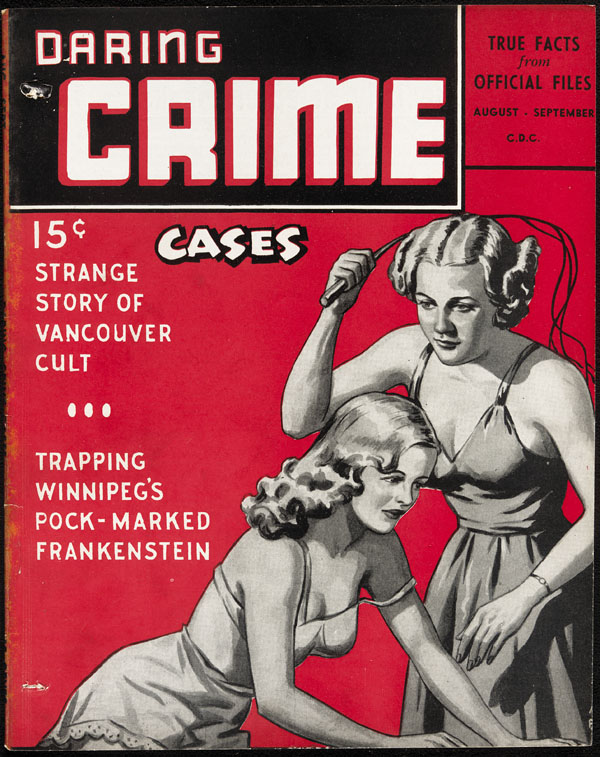

But the pace of publishing demanded more and more stories. In English Canada, most titles were published monthly or bimonthly, and could contain as many as ten stories apiece. To keep up with the need for content, pulp publishers increasingly solicited stories from Canadian writers and accepted stories set in Canada. Suddenly, in a medium once dominated by American stories, characters and settings, reader became enthralled by such tales as “The Strange Story of Vancouver Cult” or “Trapping Winnipeg’s Pock-Marked Frankenstein.”

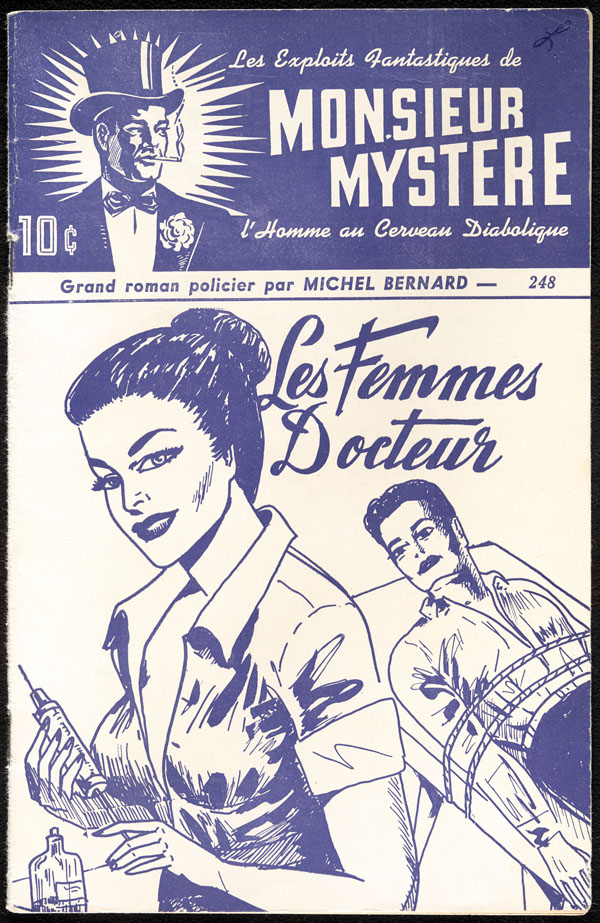

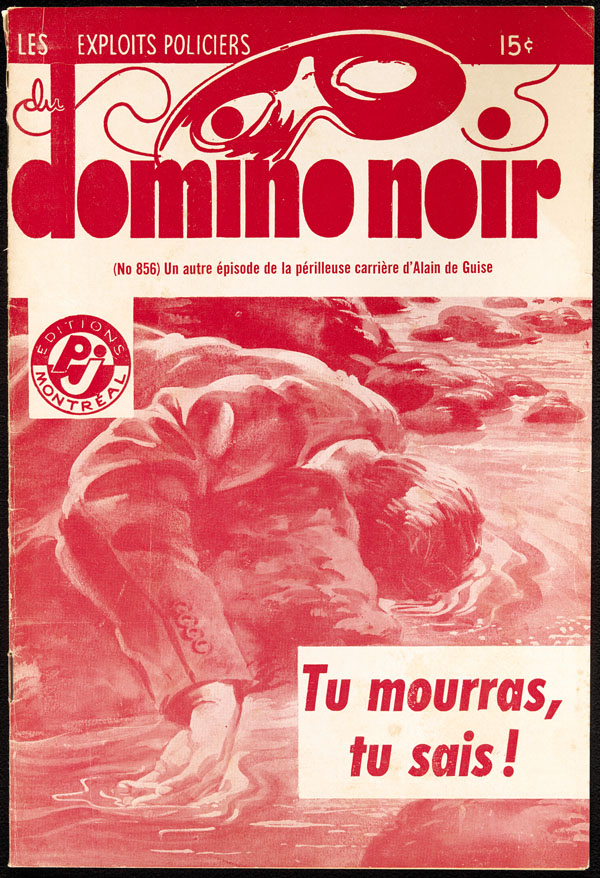

In Quebec, where many titles were published weekly, a pattern of publishers relying almost entirely on homegrown talent emerged, in addition to reprints or serializations of older stories by European authors. Sources of French-language writing were limited. Few American writers would have had a sufficient command of either the French language or Quebec culture to create a story for Les exploits fantastiques de Monsieur Mystère, or Les exploits policiers du Domino Noir.

Canadians were writing. Canadians were publishing. Canadians were reading. The Canadian pulp publishing industry was in its golden age.