Sometimes you get lucky and find a movie that’s not all that well regarded critically but which hits all sorts of notes for you, and a recent discovery, The Four-Sided Triangle (1953), was that for me. An early release of Britain’s mighty Hammer Film Productions, it sure does a lot for the thaumatophile, it’s a personal identity porn forerunner to Hammer’s Frankenstein Created Woman. And it pleases me all the more because my learning of it came from a different post at Erotic Mad Science, one presenting my then-latest search after tube girls.

Plot background: In the sleepy English village of Hardeen impoverished boy genius Bill, the son of the local squire Robin and blond beauty Lena grow up together as best friends. Bill comes under the tutelage of the kindly but slightly dim Dr. Harvey. Lena is in time taken “back to America” by her mother (a good writing cover for the fact that adult Lena will be played by American actress Barbara Payton and won’t really have the accent), while Bill and Robin go off to Cambridge to learn science. Bill and Robin will return to Hardeen and set up shop in an old barn, working on a mysterious mad-sciency project funded by Robin’s father Sir Walter.

Lena returns to Hardeen a little later, a broken woman very young: she’s tried many things and failed and returned essentially to die, as she tells a shocked Dr. Harvey in a line whose nihilistic spirit might have come from Iris Brockman.

Lena

I thought doctors were supposed to understand how little life really matters. There are many scapegoats for our sins and failures, and the most popular is Providence. I shan’t blame anyone but myself. I didn’t ask to be born, so I have the right to die.

(This is perhaps a little scary in hindsight for a reason in addition to the obvious one, given that Barbara Payton was at this point in her career in a downward alcoholic spiral that would lead to her own death at 39.)

Well, Dr. Harvey is having none of that, so he re-introduces Lena to her two childhood friends. Things go well, as Lena rejoins them as an assistant.

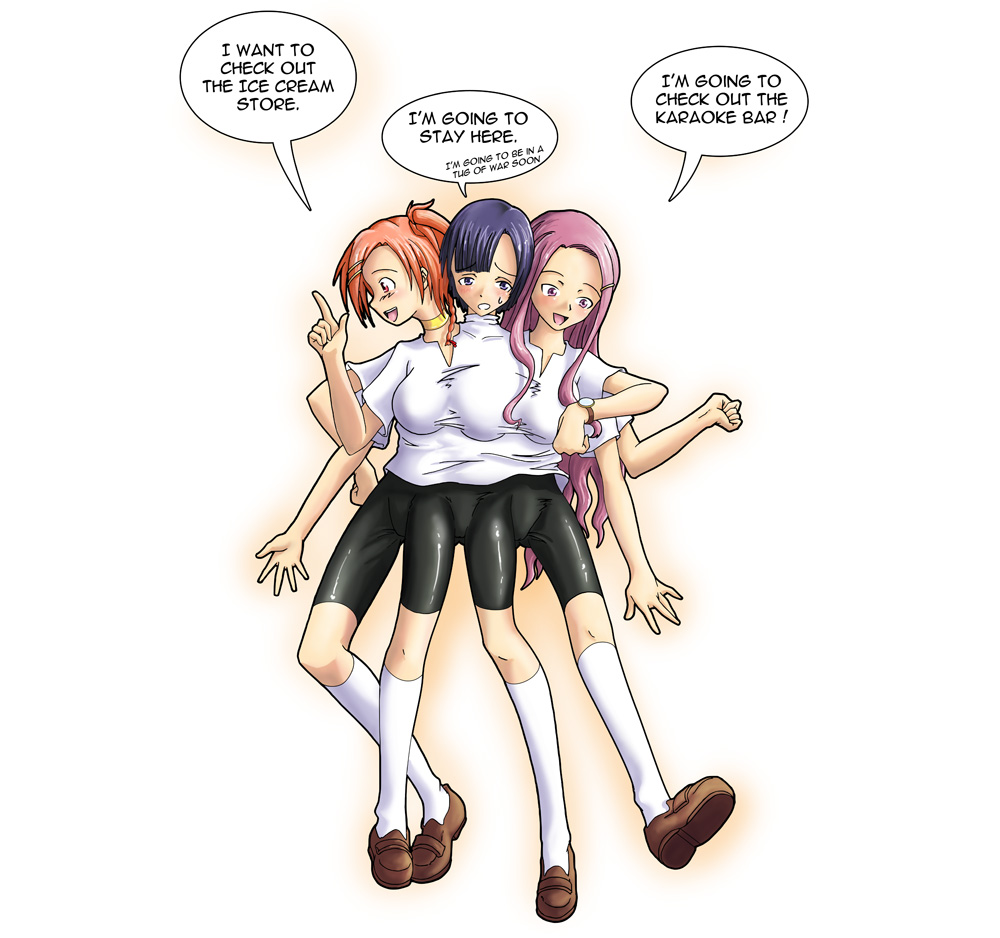

It turns out that Bill and Robin are working on a technology that allows them to reduplicate material objects with perfect fidelity. After much effort they succeed. Unfortunately, things don’t go so well on a personal front. Love walks right in and wrecks destruction, as love has a way of doing. Bill and Robin both fall in love with Lena. Repressed-but-sensitive genius Bill dithers over expressing his feelings, while self-confident upper-class Robin has no such hesitation. Robin proposes marriage to Lena, who accepts happily, leaving Bill devastated.

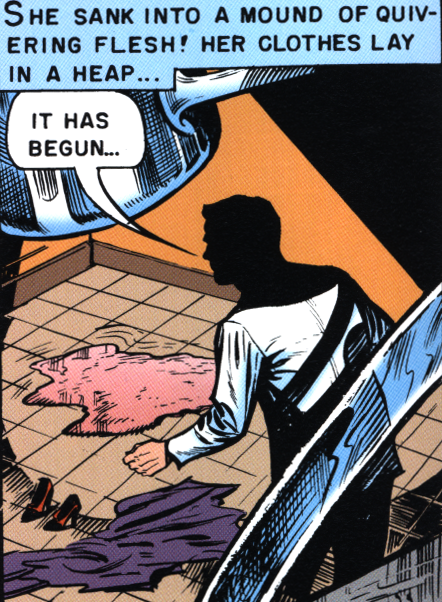

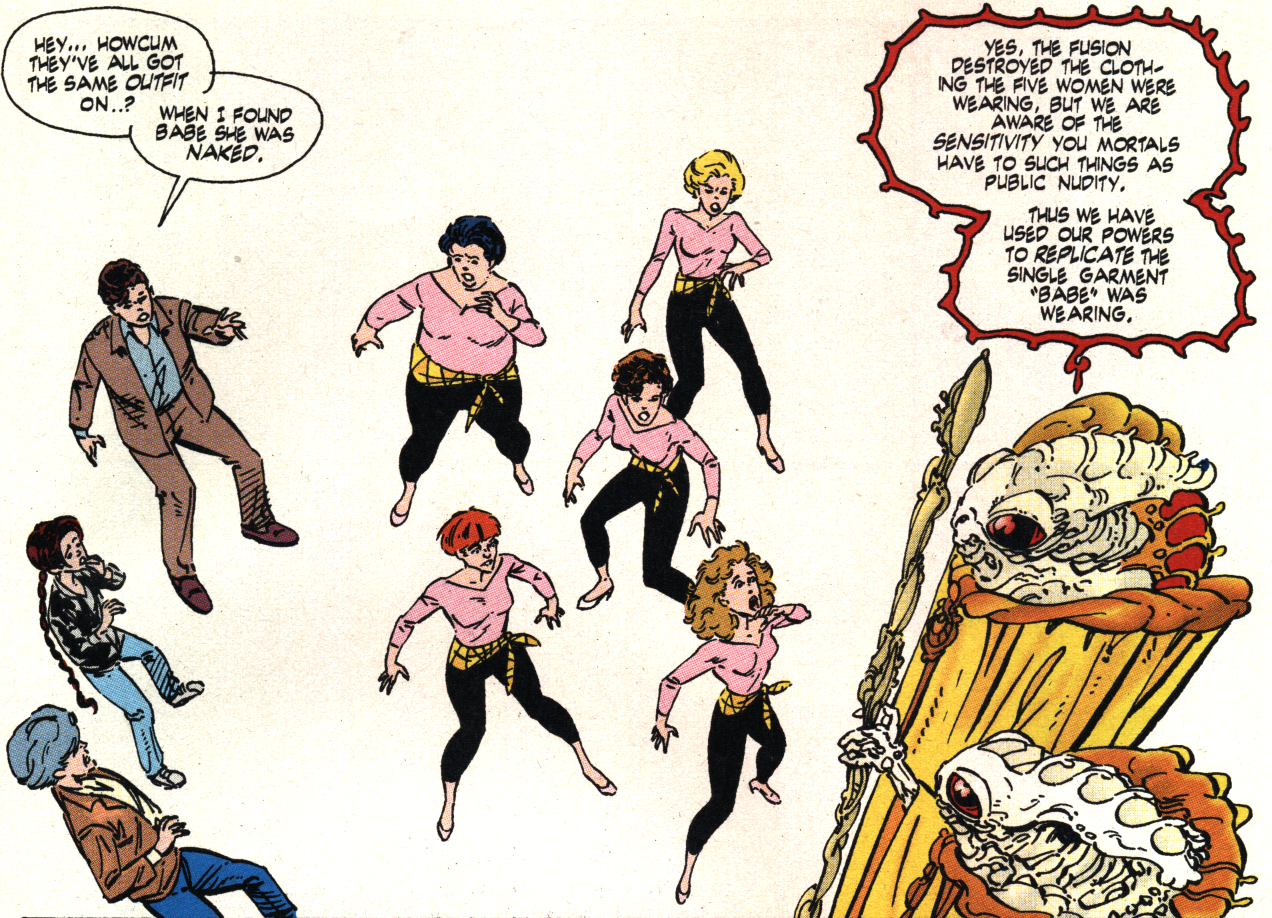

Soon Dr. Harvey finds Bill back in the laboratory, this time using his reproducing technology to recreate not just inanimate objects but living animals and…can we see where this is going, fellow thaumatophiles? Yes we can. Bill is planning to make a duplicate Lena for himself.

And here is where The Four-Sided Triangle takes a more interesting turn. Instead of following a more traditional mad-science script in which Bill would kidnap Lena and have his way with her, Bill instead explains what he wants to Lena, and tender-hearted Lena agrees to take part. Not that I want to dis the traditional plot, which certainly has its appeal, but at least this time I like the way this one was written so much better. Do you remember, dear readers, my post on The Invisible Woman?

Let’s reflect on what Kitty has implicitly gone for here: “So, you want me to take off all my clothes, step into this machine that has hitherto never been tested on a human being, zap me with heaven-knows-what, and turn me invisibile? Sure, I’m game!”

I think I’m in love.

Well, I think I’m in love all over again (perhaps I’m about to get destroyed, who knows?).

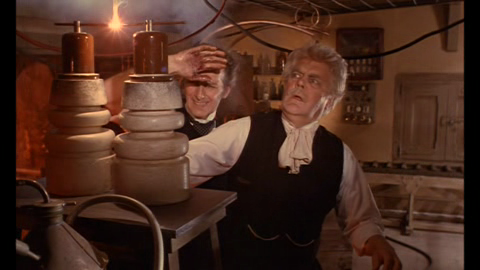

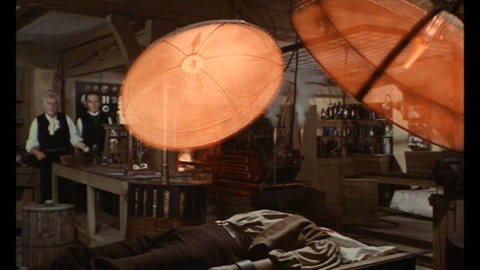

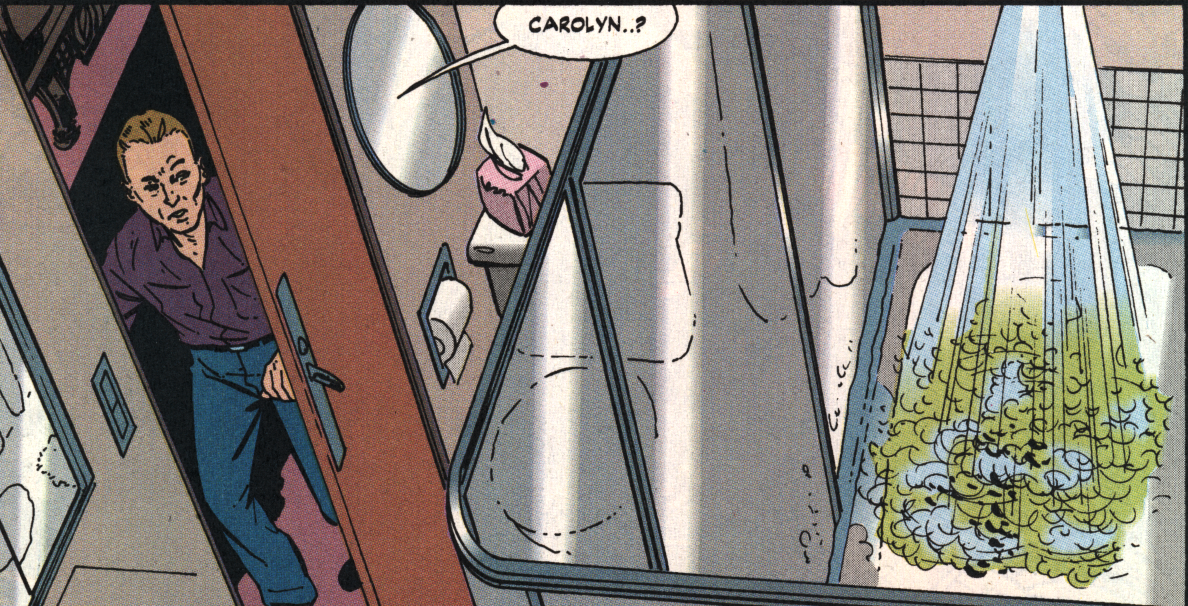

So Lena climbs into the apparatus. Switches are thrown, lights flash, and so on. Do you see the eccentric arrangement of the glowing tube in the background? The people who made this film knew their mad science cinema. They’re paying tribute to German Expressionism here, to Metropolis and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, or my name ain’t Faustus.

And of course, there’s the tube girl thing going on here as well. Although contrary to tube girl tradition, and for that matter the “girl in the machine” precedent set by Kitty Carroll herself, she leaves all her clothes on.

Now why is that? Doesn’t wearing clothes somehow make the whole duplication process a little more complicated? This is dangerous stuff, people, and we need to do things right!

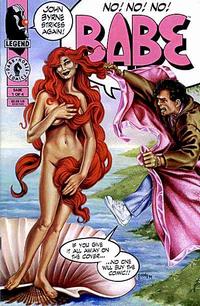

Oh wait, there’s that placard that I now remember from the beginning of the movie:

Okay, I get it now.

So anyway, the duplication process works once the duplicate is revived and Bill finally gets the love of his life.

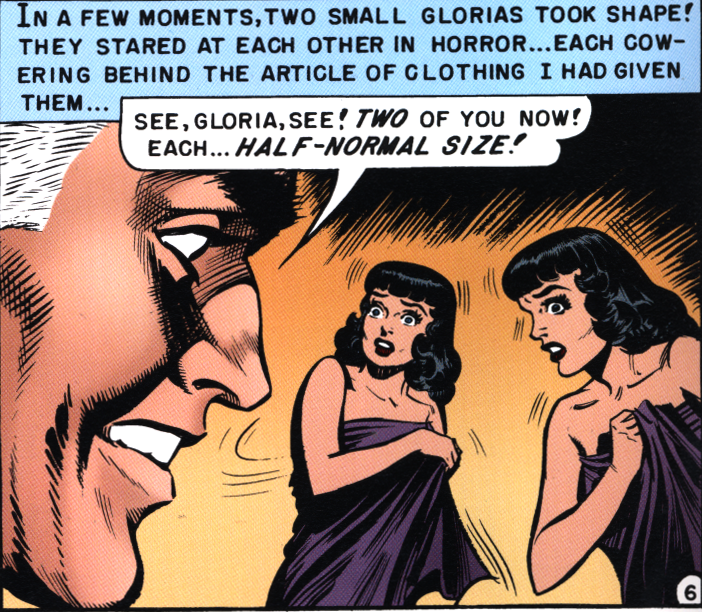

Bill names the duplicate “Helen,” and they set off for a happy holiday together.

Only things don’t work out that well, because Helen is psychologically identical with Lena, and that means she still loves Robin. Uh oh. After a suicide attempt, everyone agrees to a radical measure — electroshock therapy to try to wipe Helen’s memory and give her a clean start. Significantly, Helen herself agrees to this. This is one amazing mad-science woman.

And maybe things work, but at this point the movie chickens out and runs away from its premise. An electrical short happens, the lab burns down, and Bill and either Helen or Lena are lost to us.

That’s unsatisfying, but the movie still has a lot going for it, because it’s the cinematic playing-out of the old dream, brought to me originally through the study of philosophy, and discussed in my Thaumatophile Manifesto:

And he was also sometimes thinking about “…start with some pretty object of desire, gin up a few cloning-and-growth tanks, some superduper neurosurgery, and then maybe there will be…two objects of desire, at least one of whom might be free from certain social obligations, and..” Needless to say, the Inner Mad Scientist was chortling with delight at the prospect.

Some themes are just destined to be encountered, over and over.

Bonus animated gif from Bill and Helen’s “vacation” below the fold.